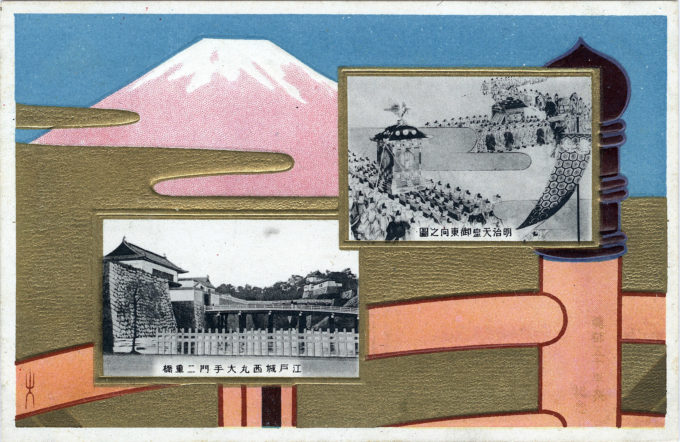

Top-right inset: Emperor Meiji’s procession to the former Edo Castle. Bottom-left inset: Ote-mon (gate) and Nijubashi Bridge at the Imperial Palace. From a postcard series commemorating the 50th Anniversary transfer in 1869 of the nation’s capital from Kyoto to Tokyo, 1919.

See also:

Exposition celebrating the 70th anniversary of the “Meiji Assembly”, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1938.

Tokyo City self-government commemoration, 1919.

The creation of “Greater Tokyo,” 1932.

“The new government’s leaders immediately after the Restoration had had no intention whatsoever of establishing a single and permanent capital at Tokyo.

“Inoue Yorikuni, for example, a scholar of National Learning and an ideologue for the early Meiji government, argued that Kyoto continued to be important as an imperial city; in fact, he maintained, the government had never even designated Tokyo as an imperial capital, a teito. While admitting that Tokyo had evolved into such a capital naturally over the years, he insisted that this had not undermined Kyoto’s ancient standing.

“As but one proof for Kyoto’s continued importance as an imperial capital, Inoue pointed out that the recently established Imperial House Law stipulated that in the future, the two major imperial rites of accession, the sokui and daijoe, must be conducted there. In Inoue’s view, Japan could have multiple imperial capitals, for the present both Tokyo and Kyoto … teito could be established in Hokkaido or even Taiwan.

“Fukuoka Takachika – the powerful Meiji political figure who had been councillor (sanyo) in the early government and who had taken part in the drafting of the famous ‘Charter Oath’ – also insisted that while it was certainly appropriate for the citizens of Tokyo to celebrate the transfer of the capital to their city, [he] repeatedly stressed that Tokyo until 1889 had been a mere anzaisho, a temporary court for the emperor on progress. ‘… Only with the move from the temporary palace at Akasaka to the present Palace (kokyo) in January 1889,’ he noted, ‘was the title of Imperial Palace (kyujo) conferred.’

“… If the task of ruling is understood to consist of simply the utilitarian mechanics of administration, the orthodox explanation of the establishment of Japan’s capital at Tokyo is quite accurate: According to this interpretation, the move of the capital took place in a rather swift, if piecemeal, fashion during the Meiji government’s first few years.

“It started with the promulgation of an Imperial Edict (taisho) in the late summer (3 September) of 1868 that proclaimed that ‘Edo is henceforth to be called Tokyo’ (Eastern Capital) and the arrival later that year (26 November) of Emperor Meiji’s first progress to Tokyo.

“Then in April 1869 the government officially announced the transfer of its highest administrative organ, the high-sounding Grand Council of State (daijo-kan), to the new capital. Soon thereafter Emperor Meiji embarked from Kyoto on a second progress to Tokyo and took up residence in Edo Castle (9 May), which had been renamed the ‘Imperial Palace’ (kokyo).”

– Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan, T. Fujitani, 1996

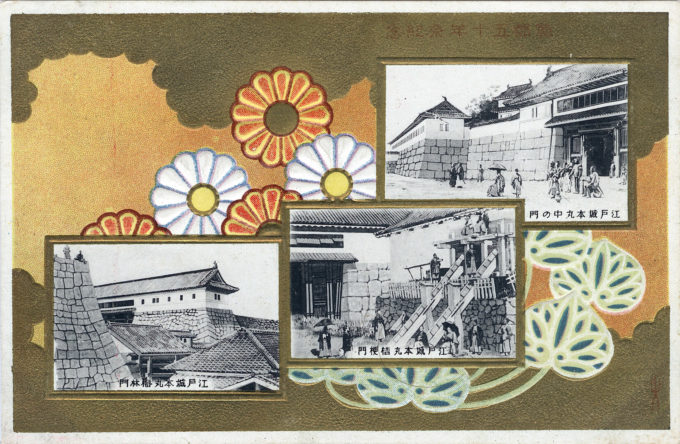

Edo Castle Inner Citadel. Left-to-right: Bairin-mon (Bairin gate), entrance to the tea ceremony house; Kikyo-mon (Kikyo gate), named after the bellflower (kikyō), which was derived from a family crest seen during the construction of the Edo Castle; Inner gate, entrance to the castle’s innermost sanctum, Honmaru. From a postcard series commemorating the 50th Anniversary transfer of the nation’s capital from Kyoto to Tokyo, 1919.

“Two weeks after the restoration of imperial rule was formally proclaimed, and immediately preceding the Battle of Toba-Fushimi between January 27-31, 1868 that would result in the decisive defeat of the Shogun’s army marching on the imperial capital of Kyoto, a white paper was submitted to a meeting of the Great Council of State (daijo-kan) for the relocation of the imperial capital from Kyoto to Naniwa (Osaka), deemed the most suitable site.

“While the proposal was first met with strong opposition from more conservative nobles – if the capital was removed from Kyoto, it would mean the abandonment of a 1000 years of history – it would be the emperor himself who issued an edict in late summer announcing the name-change of the Tokugawa bakufu administrative capital, Edo, to that of ‘Tokyo’ (Eastern Capital), and that Edo/Tokyo would remain, at least on paper, the country’s administrative capital. It was, after all, the nation’s largest city, located centrally between the eastern and western halves of the country.

“Emperor Meiji first visited Tokyo in October 1868, a month after his enthronement, returning to Kyoto before the end of the year. A second visit was made in March 1869, and the empress joined him there in October – after which he did not return to Kyoto for two years (and then only for a short time), by which time most all of the government’s central functions, including the all-important finance and military agencies and, most tellingly, the Imperial Household Agency, had also been removed from Kyoto to the new capital.

“Even though the official proclamation would not be made until 1889, on the eve of the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution, Tokyo had become, for all practical purposes, the de facto imperial capital of Japan.”

– Wikipedia