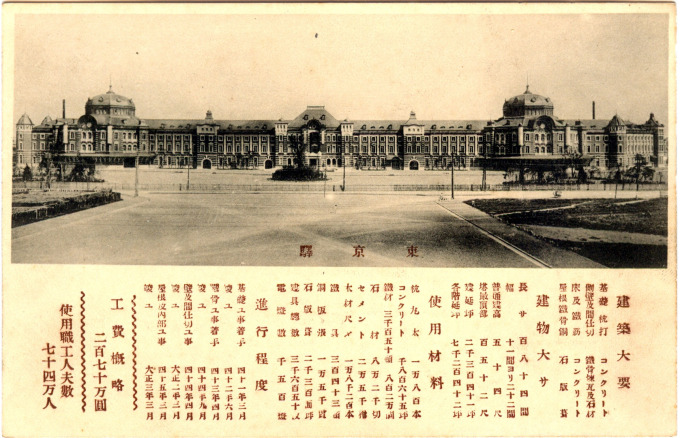

Tokyo Central Station, shortly after its opening in 1914, with construction details (e.g., how many bricks, how much concrete) listed below.

See also:

Interiors, Tokyo Central Station, Tokyo, c. 1914.

Tokyo Station, 1945-1960.

Tokyo Station Hotel, c. 1920

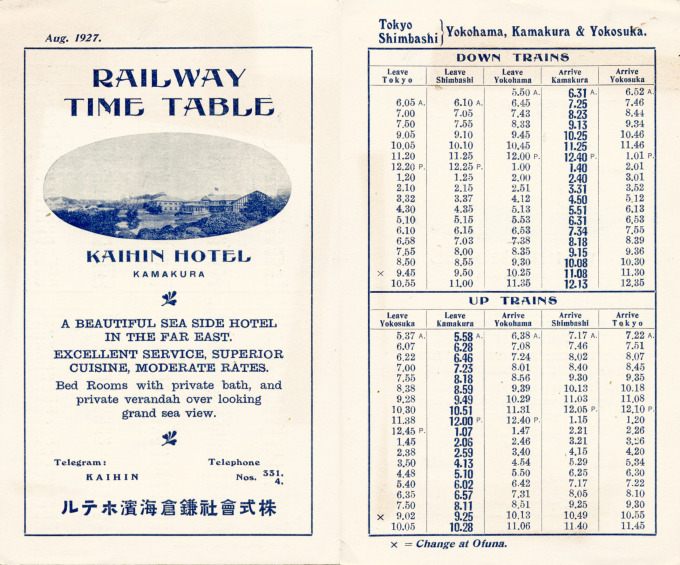

“The Central Railway Station now under construction at Eiraku-cho, Kojimachi, Tokyo, will when completed rob Shimbashi of the honour of being the ‘front door’ of the Japanese capital. The Director of the construction branch of the Japanese Railway Board, Mr. Takeyoro Okada, hopes to have the station ready for general use in June, 1914. Shimbashi will then become merely the freight depot of the Tokaido line.

“… There will be eight platforms, all built on the elevated line. Of them two will be reserved for the electric line, and four will be devoted to the Tokaido line, while the other two will be placed at the disposal of the Central Eastern [Chuo] line. The main building will have four entrances in the front, of which one in the center will be used only by the Imperial personages and their suites.

“… In view of the completion of the station the price of land in the neighborhood has risen considerably.”

– The Far Eastern Review, April 1913

“Tokyo Station was built against a background of growing Japanese competence in transportation technologies, the increasing importance of transportation to the centralisation of state power, and the international context of railways and capital-city stations as the expression of national confidence and authority.

“… The central role of Tokyo Station in nation and state was accentuated by its role as the emperor’s own station, from which he embarked on state visits. The main entrance faced the Imperial Palace across the moat, and at the heart of the station complex were the grand portico and reception rooms for the emperor and members of the imperial family.

“The architectural design paid unequivocal homage to the authority of the imperial institution, with the design focused on the central Imperial Entrance with its emphatic portico and flowing Neo-Baroque pediment. The reservation of the most impressive and central entrance for the exclusive use of the imperial family is a familiar strategy in the use of architecture to enhance authority.

“… Tokyo Station was to serve as the visual centrepiece of the business and administrative district in the city of Tokyo, the area now known as Marunouchi. In doing so it emphasised the relationship between the Imperial Palace and the emerging status of Japan.”

– Architecture and Authority in Japan, by William Howard Coaldrake, 1996

A view of Yamanote Line (center) and Tokaido Main Line (right) trains leaving Tokyo Central Station, Tokyo, c. 1920.

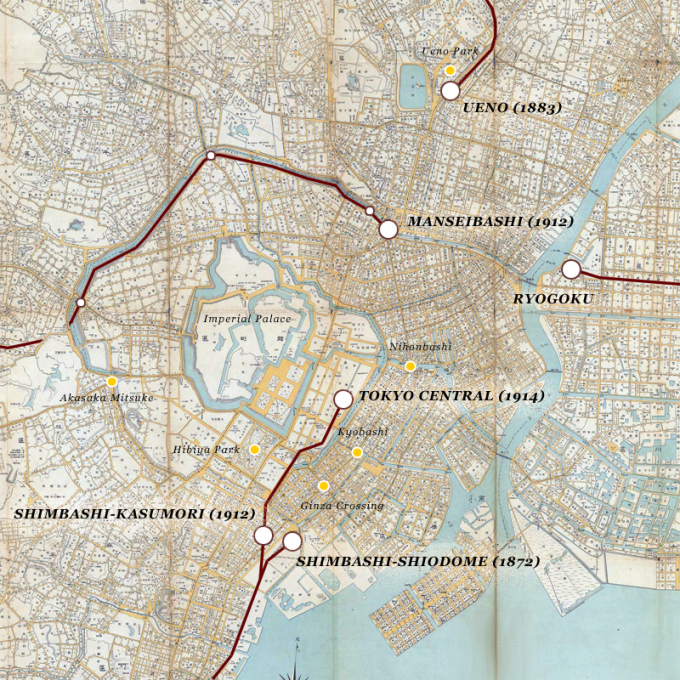

In 1889, the Governor of Tokyo prefecture issued the Tokyo City Improvement Ordinance, setting in motion the construction of an elevated railway line between its then-main two terminals, Shimbashi and Ueno. (It would not be completed until 1927 because of land acquisition difficulties between Kanda and Ueno.) The Tokyo prefectural government also established a plan for the installation of a central station in the middle of Tokyo around the same time.

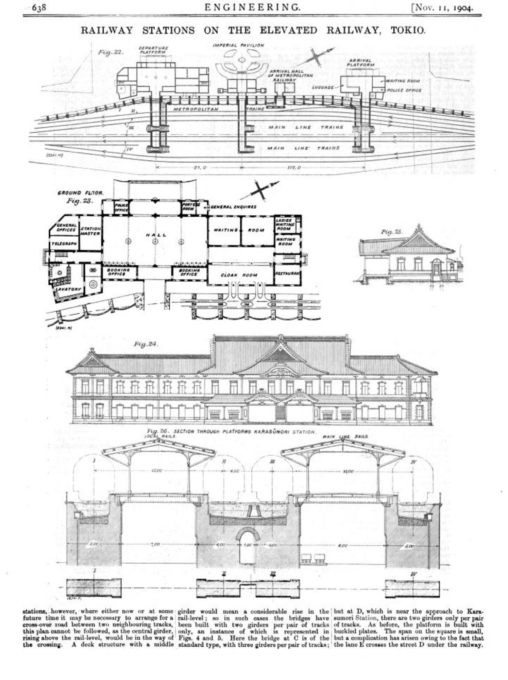

The original plans for Tokyo Central Station, 1904, showing the Momoyama-style design by Kingo Tatsuno as originally envisioned. Emperor Meiji would famously express his dislike of the original design by remarking, “Stations and like things are best rendered in a foreign style.” [Source: Engineering, Vol. 78, Nov. 11, 1904.]

The survey and early scheme of the station were initially entrusted to Hermann Rumshottel and Franz Baltzer, German engineers who were also involved in the design of the elevated railway. In 1903, the Japanese architect Kingo Tatsuno, known already for designing the headquarters of Bank of Japan and established as a pioneer of Japanese modern architecture, was commissioned to design the Central Station.

The story goes that Kingo’s original design for a station was in the style of a Momoyama palace (see illustration above), ostensibly because the structure would be fronting the Imperial Palace. But, when the architect showed his design to Emperor Meiji, His Majesty remarked “Stations and like things are best rendered in a foreign style.” Kingo then returned with a design said to be derived from Amsterdam’s dramatic central rail station.

Construction work finally began on March 25, 1908, on the capital gateway that would, in time, consolidate all but one of the dozen or so government-operated rail links to and from the capital under one roof.

“Until the terminal’s completion in 1914, Tokyo had three main rail terminals: Ueno, gateway to Japan’s northern prefectures; Manseibashi, terminus for travel to and from the western provinces; and Shimbashi, the city’s principal terminal for travel along the Tokaido Main Line until the opening of Tokyo Station. (Both Manseibashi and Shimbashi terminals were destroyed in the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake.)

- Tokyo Central Station, facing the Imperial Palace and the Marunouchi business district.

- In the distance can be seen the construction skeleton of the Dai-ichi Sogo building, at Kyobashi.

- The busy terminal, with the Nihonbashi commercial and financial district in the background.

- Looking across the plaza toward Tokyo Station. The entrance to the Tokyo Station Hotel can be seen just left of center.

“When, in the first sound film to be directed by Ozu Yasujiro [in 1936], The Only Son, the hero Ryosuke’s mother comes to visit him in Tokyo, we are given a shot of Tokyo Station as the train pulls in and then low-angle shots of tall buildings from the car’s front mudguard as it takes them over the bridge and out of the city into the periphery of the suburbs.

“[Film historian] Hashimoto Osamu explains the significance of the location of Tokyo Station as the place where the ‘spatial axis of the centre-periphery’ was reinterpreted in the simple temporal antimony of modern and pre-modern:

‘As the only ‘terminal station,’ Tokyo Station connected every locale to the center, the Imperial Palace presided as the sole center of Japan, surrounded by the modern city and counterpoised to Tokyo Station. When people from the countryside arrived at Tokyo Station, they saw in front of them the Imperial Palace, the ‘true Japan,’ transcending modern Japan and integrating the whole. This was the point where all time and space in Japan was concentrated’.”

– A New History of Japanese Cinema, Isolde Standish, 2006

- Tokyo Central Station: Gateway to the city.

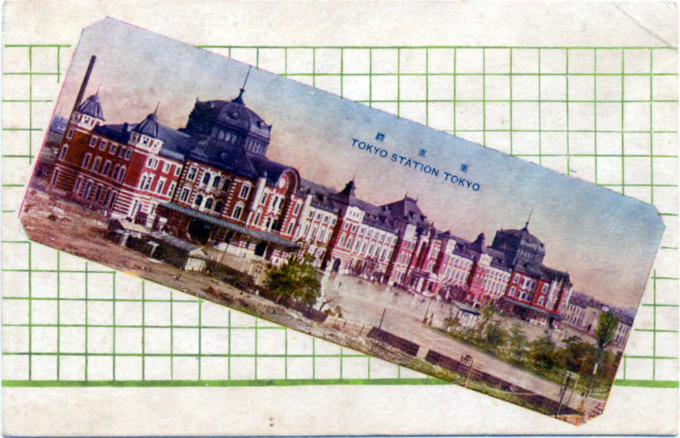

- Full-length view of Tokyo Central Station.

- Marunouchi Building from Tokyo Station north entrance, c. 1930.

- A night view of Tokyo Central Station, c. 1925.

Completed in 1914, Tokyo Central Station was built of three stories with 8.9 million red bricks. In addition to the station proper, a 90-room hotel was also included in the design. Development around the terminal was purposefully slow and methodical after the station’s completion. This was made easy, in part, because all of the property on the west side, between the station and the Imperial Palace, had been sold at the turn of the century to one company: Mitsubishi.

Deference to His Imperial Highness precluded giving much importance to the east, Ginza-facing side of the terminal; all eyes focused on the west, with it grand entrances and concourses. The east side (today’s Yaesu-guchi) would not even acquire a ticketing entrance until passenger volume finally forced the issue in the late 1930s. Even then, it had more of a temporary appearance to it (see below) than did the the permanence of development that arrived in the 1950’s as part of the terminal’s phoenix-like resurrection from the ashes of World War II.

Aerial view, Tokyo Station, c. 1940. The terminal fronted the Imperial Palace and the Marunouchi business district, with only a small entrance (seen at center) available to the Nihonbashi-Kyobashi-Ginza commercial neighborhoods, a situation that would not change until after reconstruction following the Pacific War.

Pingback: Tokyo Station, 1945-1960. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Shimbashi Station (Shiodome), c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nippon Ginko (Bank of Japan) & Mitsui Bank, Nihonbashi, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Manseibashi Station (1912-1936). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Josiah Conder: Department of the Navy, Kasumigaseki, c. 1910 | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Ueno Station, c. 1930-1950. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Shimbashi Station (Kasumori), c. 1910-1923. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Yasuda Auditorium, Tokyo University, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokyo Station Hotel, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Imperial Hemp Building, Nihonbashi, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nara Hotel, Nara, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Central Post Office, Marunouchi, c. 1931. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Dai-ichi Sogo Building, Kyobashi, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kobe Station, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokyo Kaikan, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kokugikan (National Sport Hall). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: "Города на Земле в едином античном стиле"против архитектора жд вокзала Токио 1914 год | Песчаный Воин

Pingback: Akihabara Station, Tokyo, c. 1935. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: The Second Kyoto Railroad Terminal, c. 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: 【明治・大正時代のインテリア】明治・大正時代の建築や生活について画像で解説します【日本のインテリアの歴史⑧】|インテリアのナンたるか

Pingback: Yurakucho (Tokyo) Station opening, 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Kobe Station, Kobe, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “The Emperor’s Entrance”, Tokyo Central Station, Tokyo, c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Konpiragu Shrine Treasure House, Kotohira, Kagawa Prefecture, Shikoku, c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Interiors, Tokyo Central Station, Tokyo, c. 1914. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo