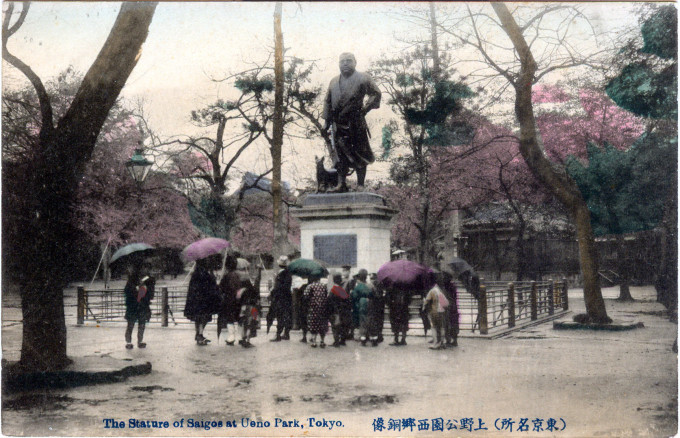

“The Statue of Saigo at Ueno Park”, Tokyo, c. 1910. Saigo Takamori is often referred to as the “Last Samurai“. He commanded the Imperial army that defeated Tokugawa forces in the Boshin War. A decade later, though, he (reluctantly) led an insurrection against the imperial government – the Satsuma Rebellion – that ended in defeat and his death.

“During these years, Saigo himself returned to his home of Kagoshima (the former Satsuma domain), also in Kyushu. There he founded a private military academy.

“His local support was so strong that Kagoshima prefecture had effectively seceded from the national government by 1876. The prefecture forwarded no taxes to Tokyo. It ignored other social reform orders of the Meiji government.

“Then, in the winter of 1877, Saigo set off with a force of fifteen thousand soldiers from Kagoshima on a march ultimately headed for Tokyo. His goal was to overthrow the government and restore samurai privilege.

“As the rebels proceeded through strongly anti-government territory in the neighboring prefecture of Kumamoto, Saigo’s army quickly mushroomed to forty thousand men. It attacked the government troops who occupied Kumamoto castle. This seige failed when a large government army (over sixty thousand men) arrived to reinforce the local garrison.

“Three weeks of bloody fighting ended in a massive defeat for the rebels. They suffered twenty thousand casualties. More than six thousand government soldiers were killed, and ninety-five hundred were wounded.

“Saigo committed suicide rather than be captured and executed. To this day, he remains a popular hero, revered as an exemplar of pure motives and loyalty to a cause, however hopeless.

“But his defeat made it clear that there would be no turning back to the old social order. Farmer conscripts had proven their worth against the samurai troops.”

– A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present, by Andrew Gordon, 2003

“To judge from the examples Morris gives us in The Nobility of Failure, more than one Japanese hero has been widely believed to have escaped death and gone into hiding in some distant land, there to bide his time until the right moment comes for him to return to Japan and finish whatever heroic work his enemies had interrupted.

“According to Ikai Takaaki, one of Saigo’s recent biographers, the rumor that Saigo had been transformed into a heavenly body began circulating within days of his death, helped in no small part by the presence of Mars in the night sky at the time.

“Ikai also reports that within a year after the defeat of the Satsuma forces, newspaper stories convinced many people that Saigo had escaped abroad and was hiding somewhere.”

– Saigo Takamori: The Man Behind the Myth, by Charles L. Yates, 1995

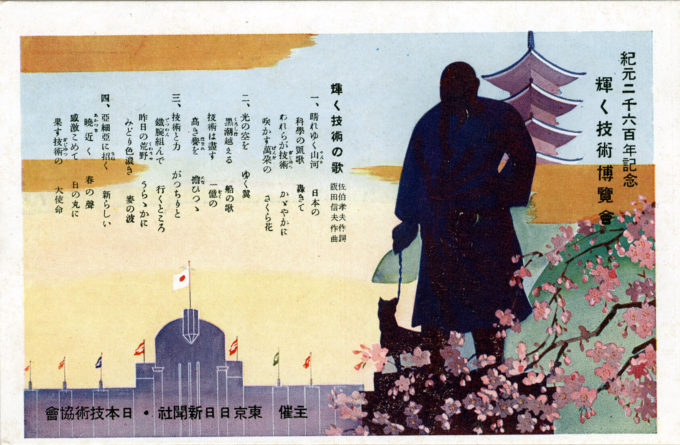

The statue of Saigo Takamori in silouette, used to promote the Exposition of Shining Technology at Ueno Park, Tokyo in 1940, in celebration of the 2600th Anniversary of the Founding of the Imperial Reign.

“Saigo Takamori was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history, living during the late Edo Period and early Meiji Era. He has been dubbed the last true samurai. During the Boshin War, Saigō led the Imperial forces at the Battle of Toba-Fushimi, and then led the Imperial army toward Edo, where he accepted the surrender of Edo Castle from Katsu Kaishu.

“A decade after the Restoration, it was Saigo who would reluctantly lead an unsuccessful insurrection — the Satsuma Rebellion — against the very same Imperial government he had previously championed. The Satsuma rebels numbered around 40,000, dwindling to about 400 at their final stand at the Battle of Shiroyama in September, 1877. Saigo died of injuries suffered in battle.

“A statue of Saigo was, nonetheless, commissioned in 1893 by the Meiji government and cast in bronze for this populist figure in modern Japanese history. However, the government chose to clothe him as a commoner, not as a military figure, a decision that irked his wife and family to no end.”

- Statue of Saigo, Ueno Park, c. 1910.

- Statue of Saigo, Ueno Park, c. 1930.

“General Saigo is a man of handsome appearance, and stately bearing, of about thirty-seven years of age; like many southerners [Saigo is a native of Satsuma province], he is by no means small of stature. His house, which we soon reach, is a wooden building in the English style. The floor of the room in which I am received is covered with a ‘tapestry’ carpet, and in it stands an American stove, which can scarcely be regarded as beautiful, though it is probably useful.

“The furniture is of European character, but surely of American make, and in pattern resembles English furniture prior to 1862. As we sat on European chairs, tea was served in native style.

“It had been arranged that I should visit Mr. Sano – one of the ministers; but Japanese etiquette demands that a note be sent immediately before the visit, to ask if all things are ready for the reception; General Saigo therefore writes the first Japanese letter which I have seen written.”

– Japan: Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufactures, by Christopher Dresser, Ph.D, 1882

- Saigo statue at Ueno Park, c. 1910.

- Rededication (above) of the Saigo statue at Ueno Park, April 2007, with descendants in attendance.

Note: I had the great fortune, during an April, 2007 visit to Tokyo, to happen upon the re-dedication of Saigo’s statue at Ueno Park that was attended by a few of his descendants.

Pingback: Ueno Park, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Japan Red Cross Society commemorative postcard, c. 1937. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Exposition of Shining Technology (2,600th National Foundation Anniversary), 1940. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Graves of the Shogitai, Ueno Park, Tokyo, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Monument of Count Goto at Shiba Park, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: The Otsu Incident—How a Goodwill Tour Sent Japan-Russia Relations Frightfully Awry | JAPAN Forward

Pingback: “Priest Gessho tsukusu ma de” (Serving Priest Gessho until exhausted), c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “Five Important Persons of the New Government”, commemorative postcard, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo