“No single object epitomized Manchukuo’s encounter with modernity more vividly and embodied its modernist urge more succinctly than the Asia Express, ‘the last word in modern steam railway transportation.’

“This ultra-modern high-speed train was the pride of the SMR’s empire and the prototype to Japan’s later bullet trains. Manufactured in the SMR’s workshops in Dalian, each train cost half a billion yen. Launched on the trunk line between Dalian and Changchun on 1 November 1934, the Asia Express was capable of travelling at 140 km per hour — comparable to the fastest trains in America and 15 km per hour faster than the fastest train in Japan.

“The streamlined Asia embodied modern luxury travel. The locomotive’s sleek elegance was more at home on a science fiction set than on Manchuria’s vast plains. Built of aluminum and sheet metal, it was lightweight and furnished with the finest materials and equipped with the latest technologies. The modern travelling experience was enabled and transformed by air-conditioning, rare hardwoods, linoleum surfaces, and silk velvet fabric covering wire-sprung seat cushions.

“Each locomotive was painted a deep indigo and pulled six coaches painted rich olive with a white streak down their sides. One entire carriage was devoted to baggage and another to dining with a kitchen, refrigerator, and space to seat 30 passengers at a time. The remaining four carriages comprised two third-class compartments each seating 88 passengers; one second-class compartment accommodating 68 passengers, half of who could enjoy revolving seats that could change direction; and a first-class carriage accommodating 60 passengers who not only had revolving seats but also enjoyed the privilege of an observation car at the rear of the train that offered panoramic views of the passing landscape.

“… This extraordinary train upended the modernist mantra that modernity travelled from centre to periphery; new to old, progressive to backward, urban to rural, West to East. The Asia Express linked Manchuria’s cities and countryside and switched modernity’s direction from East to West — Empire to Motherland.

– Ultra-Modernism: Architecture and Modernity in Manchuria, by Edward Denison & Guangyu Ren, 2016

The “Asia Express”, Shougaku Sannensei [Elementary Third Grade] manga advertising postcard, Manchukuo, c. 1935. A high-speed steam locomotive built for the South Manchuria Railway (Mantetsu) pulls the Asia Express. Such images graced fliers, posters, postage stamps, and even children’s school textbooks, as a symbol of technology and modernism in Manchukuo and were used to demonstrate the success of Japan’s colonization. Shougaku Sannensei was first published in 1925 by Shōgakukan (along with sister publications for first- and second-graders) as an educational manga and general lifestyle magazine for third-grade elementary school students. Distribution of the magazine continued through the war and postwar years until it ceased publication in 2012.

See also:

South Manchuria Railway Co., c. 1930-1940.

C55 Streamlined Locomotive and Mt. Fuji, c. 1940.

“The railway exemplified Japanese apprehensions of this relationship between modernity in the West, Japan, and the empire … [T]he locomotive emerged in the Meiji period as a popular icon of civilization and progress. It was first introduced into Japan in the miniature form of a ‘fire-wheeled car’ model that American treaty seekers brought with them in the 1850s to impress Japanese with the technological might of the West.

“The Meiji government was convinced, and actively promoted railway construction as part of its program to encourage economic development. The first line connecting Tokyo’s Shinbashi with Yokohama was opened in 1872; by 1905 nearly 5,000 miles of railway line linked urban and rural communities on all four of the main islands of the Japanese archipelago.

“… In the early decades of colonial rule this Western import acquired an imperial facade, as Japan built railways in Taiwan and Korea, and expanded the South Manchurian network taken over from Russia. Like the image of the railway in Japan itself, the colonial railroad represented an engine of civilization and progress.

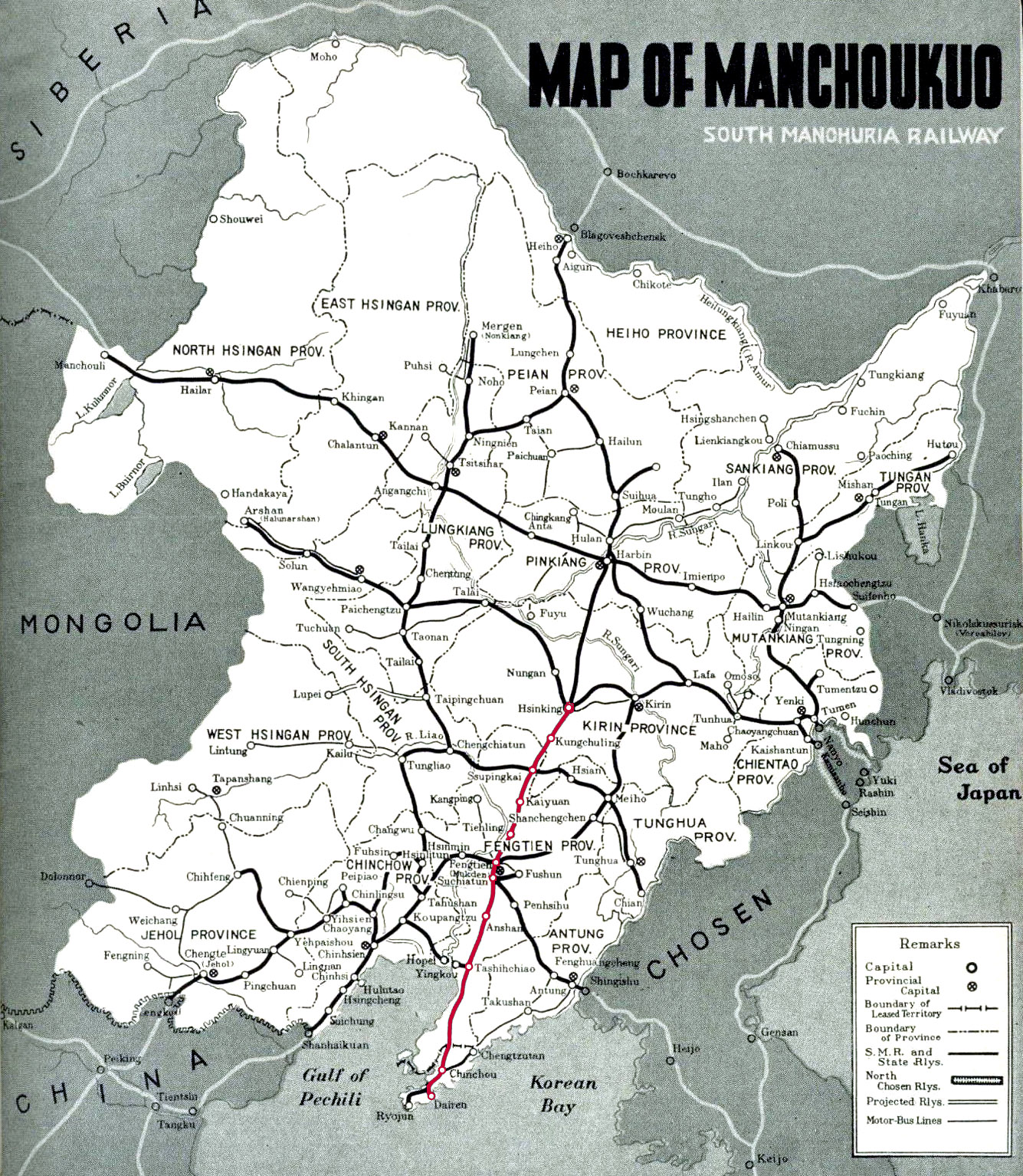

Map: South Manchuria Railway, 1940. The “Asia Express” route between the strategic port of Dairen and the capital of Manchukuo (Manchuria), Hsinking, is highlighted in red. [Source: Trains, 1942]

“In Manchukuo, the development of the high-speed ‘Asia Express’ took this one step further. Surpassing records in Japan and matching the railway technology of the West, the Asia Express became the symbol of an ultramodern empire where technological feats opened up new vista of possibility for Japan.

“Inaugurated in 1934, the Asia Express ran from Dalian to Xinjing, making intermediate stops in Dashiqiao, Fengtian, and Sipingjie. The whole trip took eight and a half hours, with the train traveling at an average speed of 82.5 kilometers/hr – 15 km/hr faster than its closest rival in Japan … New more powerful engines were encased in an aerodynamically streamlined shell, turning the complex contours of the engine car into a flat tube and giving the train a sleek, modern look.”

– Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, by Louise Young, 1998