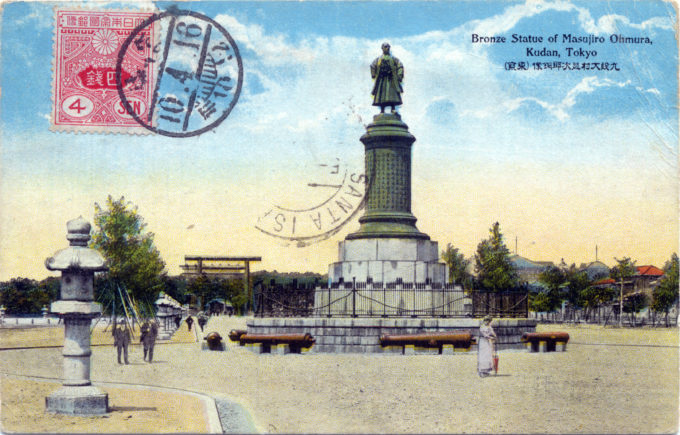

“[A] tall bronze monument, erected in 1882, on a cylindrical base midway of the [Yasukuni] esplanade, surrounded by an iron fence made to represent arrows and sentineled by a number of dismounted cannon, stands to the memory of Omura Masujiro (whose statue crowns the pedestal), a heroic and prominent figure of the Restoration.

“It was he who instructed the samurai of Choshu in the military arts, and during the which preceded the Imperial Restoration, he fought against the shogun at Yedo and Wakamatsu – later pacifying the N.E. region of Honshu Island.

“When he had been appointed the Vice-Minister of War, and diligently reorganizing the army, he was assasinated along with five of his officers.

“The striking figure (better than certain other bronze statues in Tokyo) is interesting in that it was the first bronze statue to be erected to a Japanese in the Empire.”

– Terry’s Japanese Empire, by T. Phillip Terry, 1914

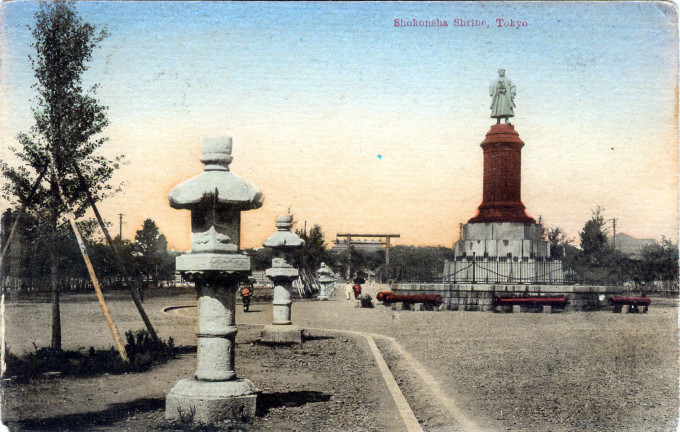

Bronze statue of Omura Masujiro, founder of modern Japanese Army, at Yasukuni (Shokonsha) Shrine, c. 1920. Omura Masujiro was assassinated in 1869, and his statue was erected in the Yasukuni Jinja grounds in February 1893. It was the first bronze statue of a Japanese person to be erected in Japan.

See also:

Yasukuni Shrine at Kudan, Tokyo, c. 1910

Kudanzaka (Kudan Slope), Tokyo, c. 1910.

“The shrine grounds were still quiet in those days. The cherry trees had only just been planted and were still small. The bronze statue of Omura stood all alone, except for the huge ungainly iron torii that towered overhead and looked completely out of place.

“… I remember the time the statue of Omura was erected, and the time when a fence was put around it. I remember the pair of stone lions being put there, after being seized at Hai-ch’eng in the war with China [1894-1895]. I remember Yoshida Banka’s large stone column being put up, inscribed with the name ‘Yasukuni Shrine’.

“I used to wander through the grounds towards the shrine, once an innocent youth, and once a promising young man full of ambitions, and once a young man with a head full of beautiful visions and sentimental thoughts of love.”

– “The Park in Kudan”, by Tayama Katai, Thirty Years in Tokyo, (Translated by Kenneth G. Henshall, 1987)

“Ōmura Masujirō (18241869) was a Japanese military leader and theorist in Bakumatsu period Japan (the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended in 1867). He was the ‘Father’ of the Imperial Japanese Army, launching a modern military force closely patterned after the French system of the day.

“Soon after Ōmura’s death in 1869 (from wounds suffered after being attacked by eight disgruntled ex-samurai), a bronze statue was built in his honor by Ōkuma Ujihiro in 1893. The statue was placed in the monumental entry to Yasukuni Shrine, in Tokyo. The shrine was erected to Japanese who have died in battle and remains one of the most visited and respected shrines in Japan. The statue was the first bronze, Western-style sculpture in Japan.”

“From a young age, Ōmura had a strong interest in learning and medicine, travelling to Osaka to study rangaku under the direction of Ogata Kōan at his Tekijuku academy of western studies when he was twenty-two. He continued his education in Nagasaki under the direction of German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold, the first European to teach Western medicine in Japan. His interest in Western military tactics was sparked in the 1850s and it was this interest that led Ōmura to become a valuable asset after the Meiji Restoration in the creation of Japan’s modern army.

“In 1861, Chōshū domain hired Ōmura back to teach at the Chōshū military academy and to reform and modernize the domainal army; they too gave him the ranking of samurai. Ōmura not only introduced modern western weaponry, but he also introduced the concept of military training for both samurai and commoners. The concept was highly controversial, but Ōmura was vindicated when his troops routed the all-samurai army of the Shogunate in the Second Chōshū Expedition of 1866. These same troops also formed the core of the armies of the Satchō Alliance at the Battle of Toba–Fushimi, Battle of Ueno and other battles of the Boshin War of the Meiji Restoration from 1867–1868.

“After the Meiji Restoration, the government recognized the need for a stronger military force that placed their loyalty in the central government as opposed to individual domains. Under the new Meiji government, Ōmura was appointed to the post of hyōbu daiyu, which was equivalent to the role of Vice Minister of War in the newly created Army-Navy Ministry. In this role, Ōmura was tasked with the creation of a national army along Western lines. He also strongly supported the discussions towards the abolition of the han system, and with it, the numerous private armies maintained by the daimyō, which he considered a drain on resources and a potential threat to security.

“Ōmura argued that if ‘the government was determined to become militarily independent and powerful, it was necessary to abolish the fiefs and the feudal armies, to do away with the privileges of the samurai class, and to introduce universal military conscription.’ Ōmura’s ideal military consisted of an army patterned after that of the Napoleonic French armies and a navy that was patterned after the British Royal Navy. For this reason, even though the French government had lent tacit support to the Tokugawa regime during the wars of the Meiji Restoration through supply of weapons and military advisors, Ōmura continued to push for the return of the French military mission to train his new troops.

“Ōmura ideas for modernizing Japan’s military were largely implemented after his death by his followers such as Yamagata Aritomo, Kido Takayoshi, and Yamada Akiyoshi. Yamagata, a devoted follower of Ōmura, traveled to Europe to study military science and military techniques that could be adapted in Japan. Upon returning from Europe, he organized a 10,000 men force to form the core of the new Imperial Japanese Army. As Ōmura had hoped for, the French military mission returned in 1872 to help equip and train the new army.”

– Wikipedia