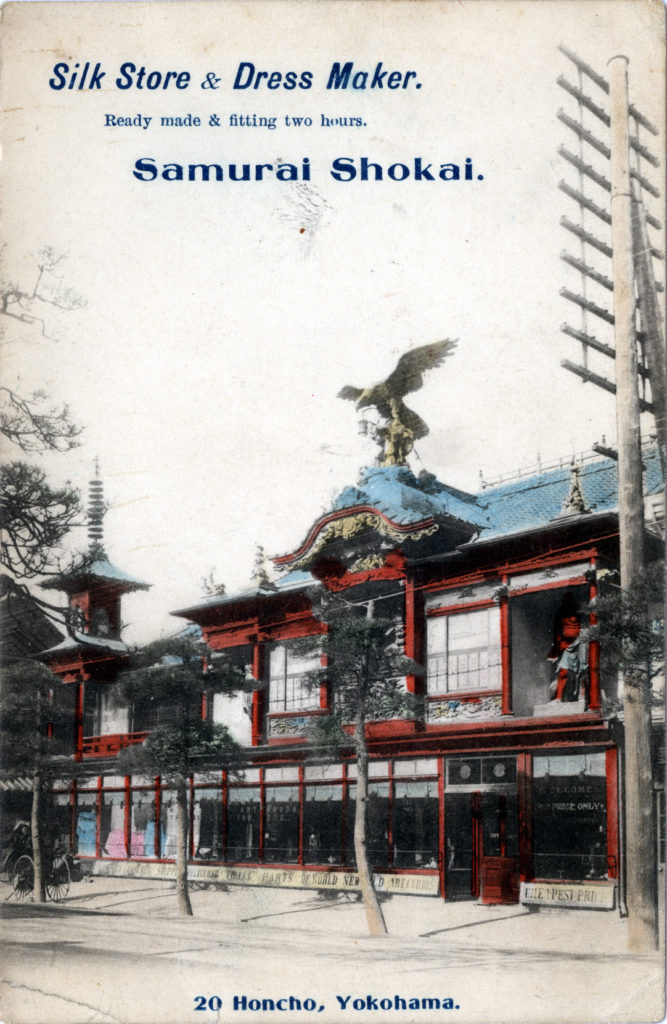

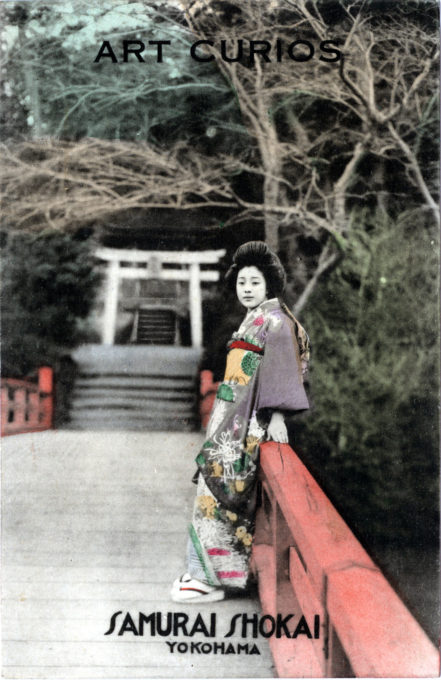

Samurai Shokai, Yokohama, c. 1930. Yokohama’s famous art curio shop, Samurai Shokai, was opened in 1894 by Nomura Yozo, the self-proclaimed “Kurio King”, who had apprenticed in the art curio business at a New York City Asian art gallery, A.A. Valentine. In its first six months, Nomura’s shop sold some 10,000 objects. Over time, purchases from Samurai Shokai would become important objects d’art of art collections at the Honolulu Academy of Art and the Sackler/Freer Museum in Washington, D.C.

“[Samurai Shokai is an] old established trustworthy house, highly spoken of, with one of the finest collections (second only in point of interest to the National Museum, at Tokyo) of curios and art objects in Japan. Recognised by antiquarians and art connoisseurs as headquarters for many of the beautiful products for which Japan is celebrated.

“The showrooms, filled with choice Japanese, Chinese and Korean carved furniture, porcelains, ivories, bronzes, brasses, silver pieces, damascene work, gold lacquer, mother-of-pearl inlays, tea-sets, chests, screens, brocades, silks; diamond, pearl, jade and other jewelry, etc., etc., rank among the city’s most interesting sights.

“English is spoken in all the departments. Prices are marked in plain figures, and there are no misrepresentations. Purveyors to the Imperial Japanese Household, and to the chief Museums of the world. Wholesale and retail. Manufacturers and exporters. Mail orders a specialty. Recommended.”

– Terry’s Japanese Empire, T. Phillip Terry, 1914

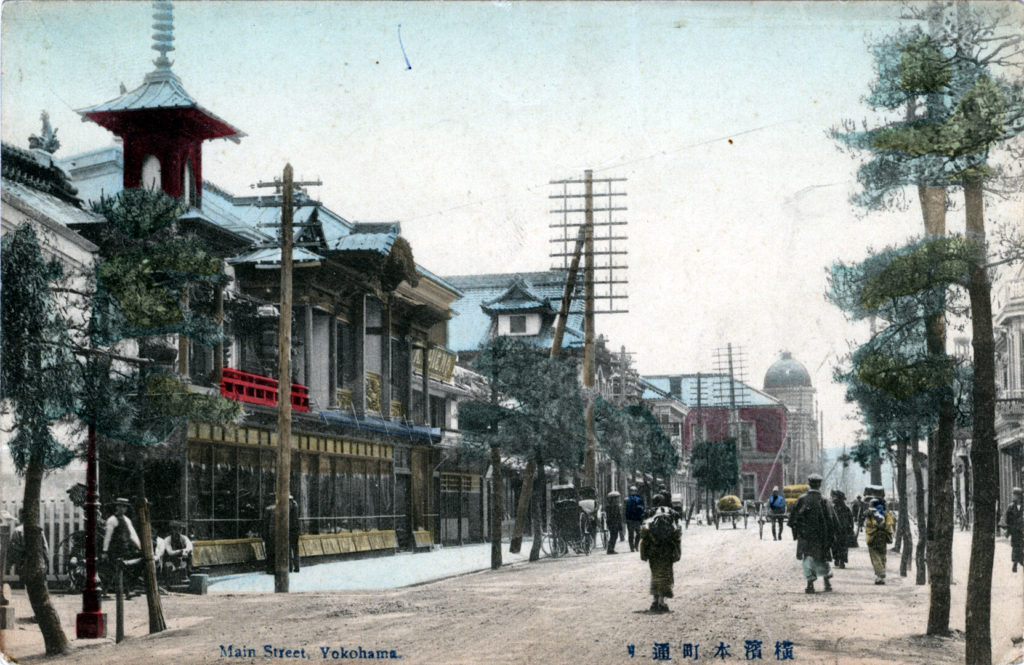

Samurai Shokai (left), on Honcho-dori, Yokohama, c. 1910. The original shop and the surrounding neighborhood would burn to the ground in the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake. Nomura would rebuild and expand his business into direct mail order, exporting all over the world, before finally closing Samurai Shokai in 1942 at the start of the Pacific War. Nomura would go to become a founding member of the Rotary Club in Japan, found the first Japanese branch of the Society for the Protection of Animals, be a director of the New Grand Hotel chain, and head the Yokohama Chamber of Commerce.

“When American tourists land at Yokohama they see just one store. They cannot help it. The signboard of the Samurai Shokai is put up on the street called Honcho at the menuki no basha (that is to say, ‘the eye pulling spot’).

“The art and curio store does more than a million yen worth of business in a year, according to current reports. It started barely fifteen years ago; it had absolutely no reputation at the time. It was started by a man called Nomura Yozo who had no commercial or financial standing whatsoever. And he started it from absolutely nothing. Mr Nomura borrowed from a friend, two Government bonds of the face value of 100-yen each, and putting them up as security he negotiated the cash loan of 175-yen ($87.50); that was all the capital with which the Samurai Shokai was started.

“… How on earth did he get the stock? He simply went to those who knew him, as well as to those who knew him not, with equal impartiality, and persuaded them to let him have all sorts of articles on consignment. He succeeded, and this initial success shows two things: his diplomatic talent and his ability in reading the nature of his fellow men.

“A customer came into his shop one day, a foreign tourist. He feasted his eyes among the art objects and curios; he was just looking around. An article caught his fancy and, in his excitement, his outstretching arm in making for it forgot another object near-by. There was a crash on the floor, and when the broken fragments were picked up one of them still held a price card … more than 100-yen. The customer was annoyed; it was enough to make anyone frown, and the frowning offender never has a sense of justice or philosophy or time to see that it was nothing but his own carelessness and clumsiness that brought about the accident. He was sour but he said ‘Oh! I’m sorry. Well, what’s the price of it? I suppose I shall have to stand for it.’

“Mr. Nomura stepped up with a nice bow, which was not unexpected in Japan, and, with a smile, a beaming summer, sunny smile, which was rather unexpected even in Japan, he said to his customer ‘Oh, not at all; that’s all right. Accidents happen. No, I don’t want any money. That is not the way I do business.’ The customer’s face was a study. ‘But, see here!’ said he, showing Mr. Nomura the price card, ‘you will lose more than 100-yen.’ ‘Yes, but if we had an earthquake, I should have lost more. It is all right. I do not wish to charge anything that my customers don’t get the full therefor.’

“‘Well!’ said the customer, slowly and with a flickering smile, and his face was a bigger study than ever before. ‘Well, all right.’ And then he began to buy. He must have been an American judging from the way he punished his pocketbook. When all his purchases were paid for, they were packed and sent to his hotel. That night, the sunny smile was still on the lips of Mr. Nomura; he had not lost one solitary cent through the smashing of a 100-yen article by his customer. That much he had known all along. But, he did not realize till he figured profits all up how very much ahead he was through a fortunate and highly profitable accident.”

– “Sales Art and Sales Artists”, Collier’s Weekly, March 2, 1912