“The Japanese word danchi may not be evocative for a foreign reader, though its present use – which appeared in the mid-nineteen-fifties – became common language here. At the time, with the rebirth of the economy, Japan began a mass-housing policy of shugojyu-takudanchi (collective housing estates) summarized in the shorter and popular danchi.

“Even though modern collective housings appeared in Japan in the nineteen-twenties, danchi was a post-war phenomenon linked with the need to respond quickly to a large increase in the urban population due to the baby-boom, the rising of the industrial production, and the rural exodus. Thus, these estates epitomize for many Japanese this period of harsh renewal.

“By 1955, semipublic institutions in charge of the construction of the danchi were establishing standards both for the types and surfaces of the apartment units and the site planning of the blocks themselves. Conditions were rather drastic with an average flat called a 2DK (2 bedrooms, a living and a dining room) of only forty-three square meters.

“… Contrary to the rejection of its American and European counterparts, Japanese danchi, though nowadays considered obsolete, have rarely been a subject of fear and hard criticism. This fate tends to be explained by various factors. First of all, one has to consider the Japanese population’s high level of civility. The danchi, though repetitive and cheaply made, have never been trashed or subject to violence. On the contrary, the first owners often stayed and organized lively communities.

“… Danchi, though foreign to the local tradition of low wooden constructions of cities, participated in a larger rejuvenation of post-war Japanese urbanity that had started in the eighteen-seventies with the political opening towards the world of previously secluded Japan. Today, [danchi] often look like convenient and green oasis within densely built Japanese cities.”

– Save the Danchi Mass Estates: A Project of the Future, published by Mikan, 2001

“The ‘dining-kitchen’ (‘DK’, a combination of dining room and kitchen), which appeared after the Second World War, decisively changed the Japanese house. A Tokyo University research group led by Yoshitake Yasumi developed the first dining-kitchen for public housing in 1951.

“… In the traditional Japanese house, the kitchen and dining room were separate … It was noisy and it smelled, for which reason it was built on the house’s north side, far from the dining room. At mealtimes a family placed a dining table in a tatami room, and at night they removed the table so that a futon could be spread. The room was now a bedroom. The multifunctionality of the Japanese room was its greatest advantage.

“In the city, however, where the home was smaller and family members might eat and sleep at different hours because the breadwinner was employed at a factory, the multifunctional room could be inconvenient. Researchers sought ways to enable residents of cramped urban housing to lead more comfortable lives. Eventually they came up with the idea of the ‘dining-kitchen’.

“The dining-kitchen is a Japanese original. Researchers wanted to separate the dining and sleeping areas in a small apartment. But they knew that most people could not afford an apartment with an independent dining room. So, as a last resort, researchers connected the dining room with the kitchen. But the view of the dirty sink, something that had always been hidden, would spoil diners’ appetites. So they rushed to develop a new sink. Hamaguchi Miho succeeded in coming up with a stainless-steel sink. Since her new sink looked like a piece of furniture, there was no reason to keep it out of view.

“… The developers of the dining-kitchen were feminists. They knew that by brining the kitchen from the rear to the center of the home they would move women from the periphery to the center of the family.

“The Japanese Housing Corporation, which was founded in 1955, incorporated the dining-kitchen in the basic plan for high-rise units. Before long the dining-kitchen, devised for a cramped apartment, was introduced in spacious dwellings.”

– “Japanese Housing Over the Centuries”, by Fujimori Terunobu, The East, Vol. 34 No. 3, Sept-Oct 1998

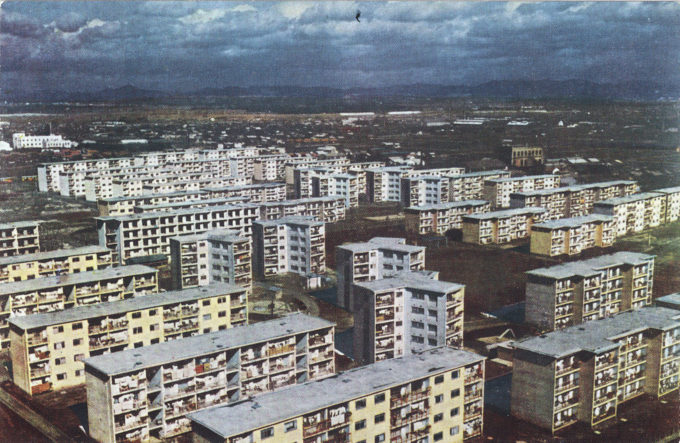

“Postwar collective housing in Japan is defined by the danchi, the complexes built by the government housing organ, Nihon Jutaku Kodan, from the late 1950s to the 1980s. Kodan, as the organ was popularly called, modeled its housing on apartment blocks built by the Soviet government in the suburbs of Moscow and Leningrad.

“According to Takashi Hara in his book ‘Danchi no Jidai‘ (‘The Age of Danchi’), the Kodan officials who brought the Soviet designs back to Japan were interested in the low-cost engineering method. However, at around the same time the administration of Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama normalized relations with the Soviets, and certain socialist ideals took hold in Japan owing to the ascendancy of labor unions, particularly among teachers.

“It was believed that true democratic principles sprung from a society where everyone’s material circumstances were the same, and the appeal of the danchi was its uniformity: concrete, gray, no higher than five floors, and all containing apartments of the exact same design.

“Though today danchi look bland and superannuated, particularly from the outside, in their day they were considered the height of modernity. Hara writes nostalgically about how classmates who lived in single-family houses envied him for living in a danchi, even though in most cases they were much smaller.”

– “Danchi housing lets you think outside the usual box”, by Philip Brasor & Masako Tsubuku, The Japan Times, November 6, 2012