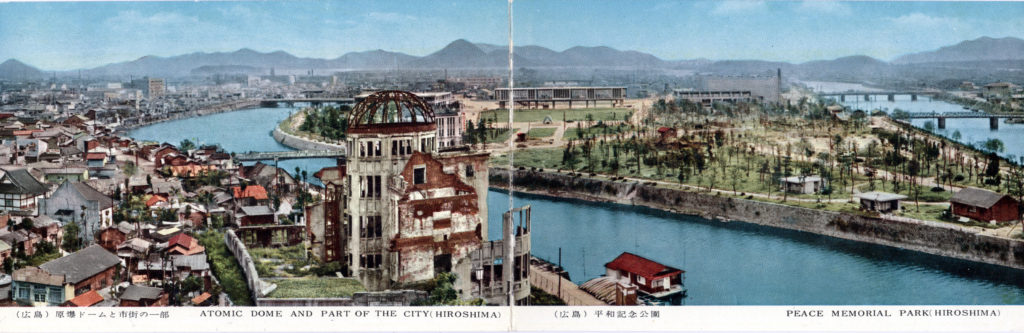

A panoramic view of Peace Memorial Park, Hiroshima, c. 1960, including the “Atomic Bomb Dome”, the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall completed in 1915.

See also:

Hiroshima Industrial Exposition, 1929.

“In the 1940s and 1950s … the dome only narrowly escaped demolition. A 1949 survey found that most residents (65 percent) wanted to see it destroyed, as it was ‘a reminder of the war and its destruction.’

“A 1951 round-table discussion with Mayor Hamai Shinzo, the president of Hiroshima University, Morita Tetsuo and other prominent figures was in complete agreement as to the need to destroy the dome. Those who called for its preservation were very much a minority in the 1950s.

“But as the debate evolved, the issue split the hibakusha [atomic bomb survivor] camp and city elites alike. The debate saw strange alliances between peace groups and tourism officials and tour companies on one hand, and real estate interests (coveting the prime downtown spot) and other hibakusha who wanted it torn down.

“The debates over the dome were far from a simple memory versus forgetting conflict. These debates illustrat[ed] the complexity of the dome’s preservation and how, like the broader debate about the Peace Park and remembrance of the bomb as a whole, all – whether they were for or against preservation – were caught in a dialectic process that domesticated and sanitized the memory of the bomb.”

– Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, by Ran Zwigenberg, 2014

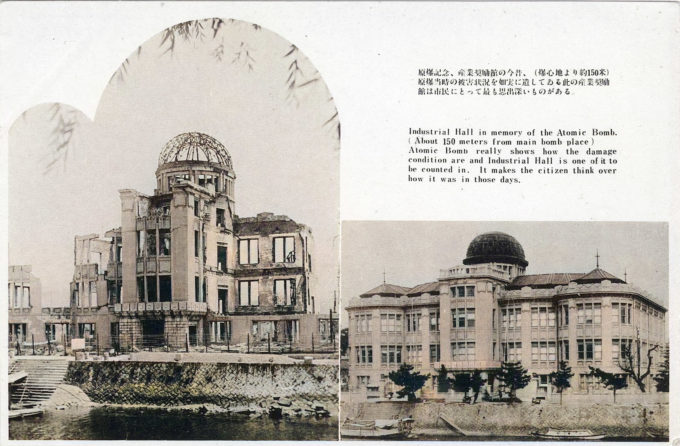

The Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Hall, Hiroshima, near the epicenter of the first atomic bomb, as seen in 1945 (left) and ca. 1920 (right). (Colorized)

“The former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was erected in April 1915. it was designed by Jan Letzel, a Czech architect [who also designed the Matsushima Park Hotel], and its initial name was the Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall. Products made in Hiroshima prefecture were exhibited and sold there. From 1933 it functioned as the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall and it stopped operations in March 1944, in the midst of the war.

“[T]he elegant-looking building with its structure reflected on the water of the river was beautiful and quite unique in the world … It was housing a number of offices at the time the A-bomb was dropped and everyone died. The copper-covered roof completely melted and only the iron frames of the building were left from the blast.

“However, after the war, some people showed a strong desire to do away with the Atomic Bomb Dome, which they considered to be a bad memory. The City Council of Hiroshima made a decision in 1966 to preserve the dome, after long and heated discussions.”

– Peace Through Tourism: Promoting Human Security Through International Citizenship, edited by Lynda-ann Blanchard & Freya Higgins-Desbiolles, 2013

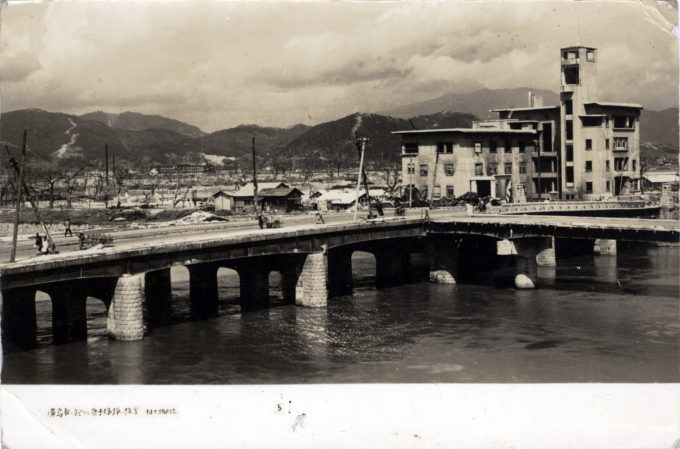

- Nagarekawa Church, Hiroshima, destroyed in the 1945 atomic bombing.

- A view of the devestation wrought at Hiroshima in August, 1945.

“In 1955, Hiroshima hosted the first World Congress against Hydrogen and Atomic Bombs (Gensuikyo). Thousands of delegates from Japan and abroad filled the Peace Park in a display of unity and optimism. Hiroshima seemed to finally be achieving the national and international status it had sought since 1945.

“The Congress offered a powerful boost to Hiroshima’s image as a city of peace. The city cooperated enthusiastically with the movement and, as a result, throughout the 1950s, Hiroshima was seen as a symbolic center for the Japanese anti-nuclear and peace movements … The city presented itself as a noble victim that harbored no ill will toward its former enemies.”

– Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, by Ran Zwigenberg, 2014

“An astonished Time magazine reporter found out in the late 1950s that, ‘In addition to tourists, Hiroshima lives by brewing beer and the building of ships – and, ironically, by the manufacture of howitzers by Japan’s biggest gunmaker, Nihon Seiko, whose sales grossed $61 million and gave employment to more than 1,500 Hiroshima citizens.’ These figures were relatively low in comparison with the numbers of the boom years during the Korean War. These were prosperous years in Hiroshima. Indeed, the city, and Japan as a whole, recovered in large degree thanks to the war next door.

“Ravaged by American arms the city recovered by building and refitting them.”

– Hiroshima: The Origins of Global Memory Culture, by Ran Zwigenberg, 2014