The Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, was held from March 10-July 22, 1922 to commemorate the end of the Great War (World War I) in 1918. Its opening coincided with the return of Japan’s delegates from the Washington Naval Conference, an attempt by the Great Powers to limit global naval military growth.

The Tokyo Peace Commemorative Exposition [Hakurankai jimukyoku] was held March 10-July 22, 1922 at Ueno Park to commemorate the fourth anniversary of the end to the Great War (World War I) in 1918. The size and beauty of the Exposition far surpassed any other fair that had been held in Japan up to that time.

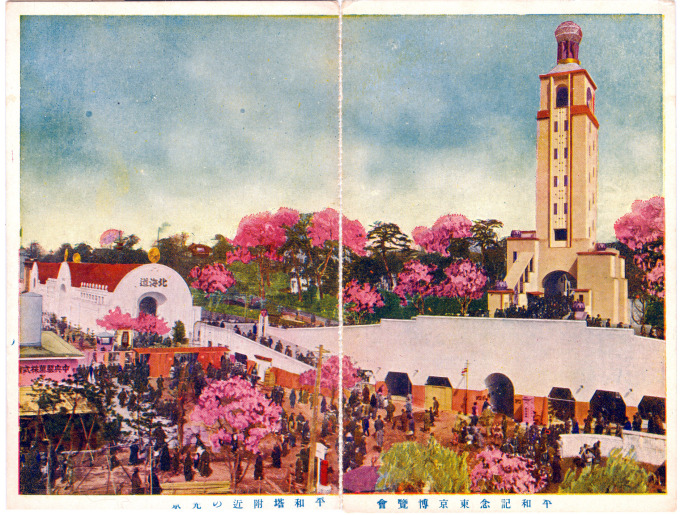

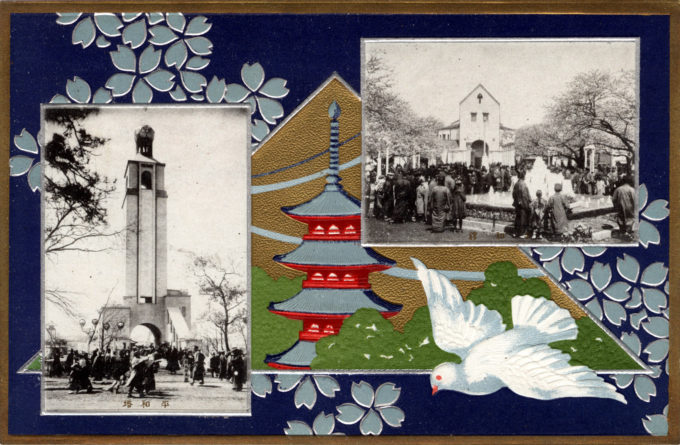

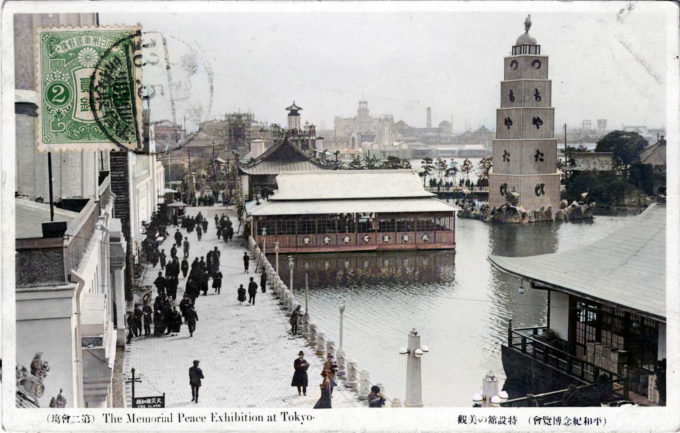

The Exposition was dominated by the Peace Tower (below), designed by Hiroguchi Sutemi and modeled after the Wedding Tower in Darmstadt, Germany.

Members of the Bunriha Kenchikukai, the Japanese “Secessionist Architecture Group” movement inspired by the Viennese Secession that was closely associated with the Art Nouveau and Modernism arts movements, designed a number of the buildings for the Exposition, along with students of nearby Maekawa Kuno’s school of architecture.

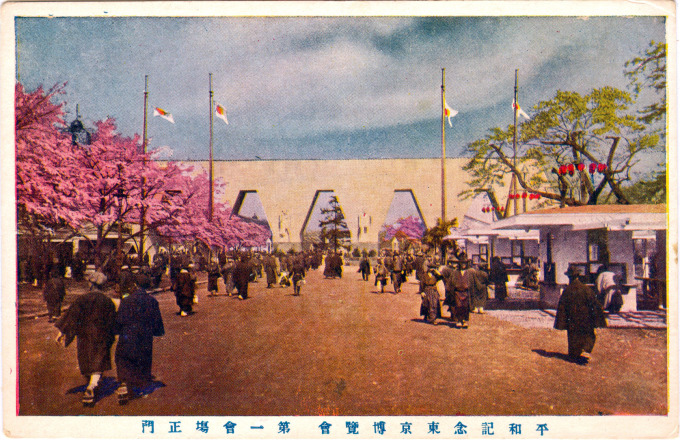

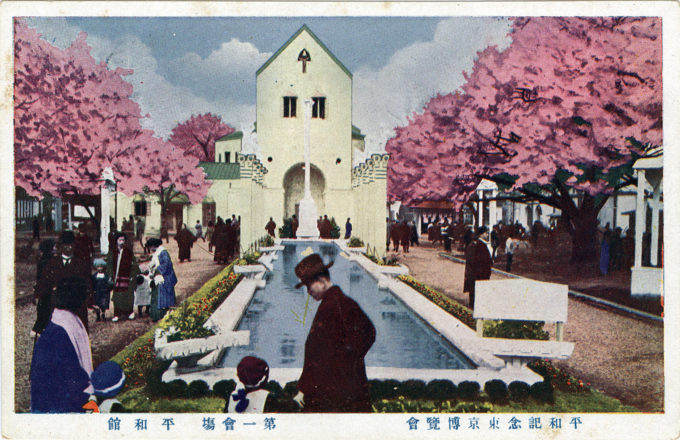

Peace Tower and cherry blossoms, 1922 Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo. The Japanese officials in charge of the exposition stated that it was to be the most comprehensive exhibit of world products ever gathered in one place. The timing of the exposition with the arrival of o-hanami (cherry blossom season) added much festivity to the occasion, increasing the symbolic association of the cherry blossom with peace.

“On the morning of the return of Japan’s delegates from the Washington Conference, Ueno Park began a joyous celebration. Though a rainy day and early for spring blossoms, the Tokyo Peace Exposition, according to the daily Tokyo Asahi, honored ‘the best of world culture’ and stood as ‘a harbringer of dazzling beauty’.

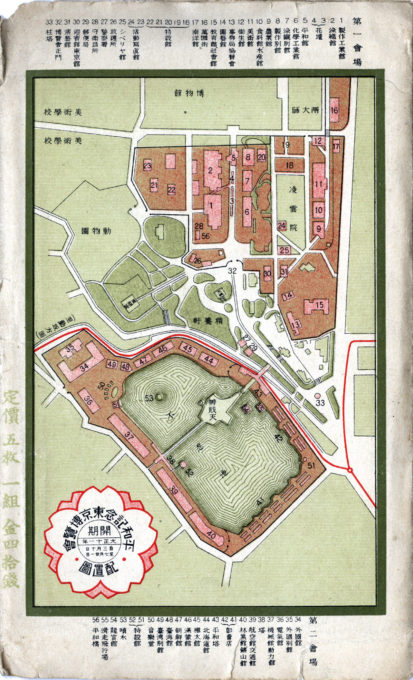

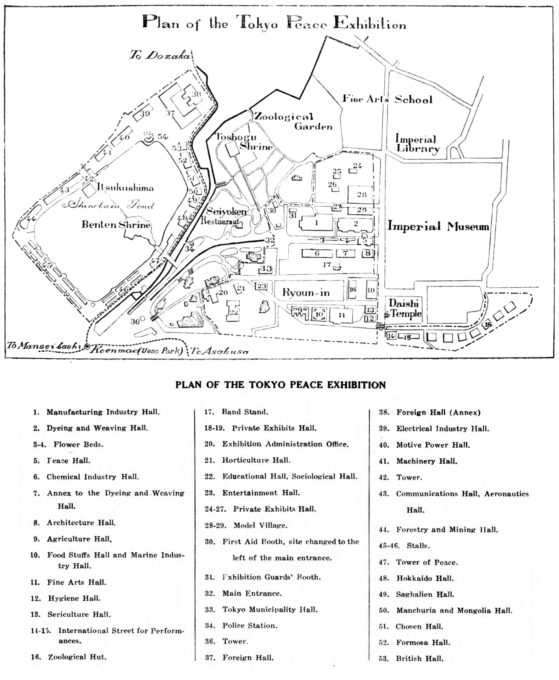

Map: Exposition layout with Japan Red Cross Society information and medical services locations, Peace Memorial Exhibition venue map, 1922.

“Costing 6 million yen and comprising almost fifty pavilions, a 110,000-sqaure-meter natural lake, two triumphal gates, a signature ‘peace tower’ and a ‘peace bell’, the four-month extravaganza became the largest Japanese exposition to date.

“… With the tolling of the peace bell, several dozen doves flew ‘happily’ toward the skies. Festival chair Prince Kan’in, backed by a stage adorned with celebratory pine, plum and bamboo, officially opened the expo by declaring world sentiment fed up with ‘the ghastly evils of war’ and ‘full admiration for the happiness of peace’.”

– World War I and the Triumph of a New Japan, 1919-1930, by Frederick R. Dickinson, 2013

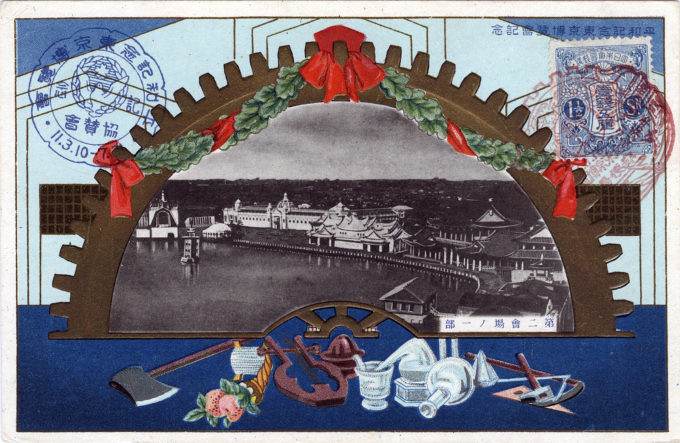

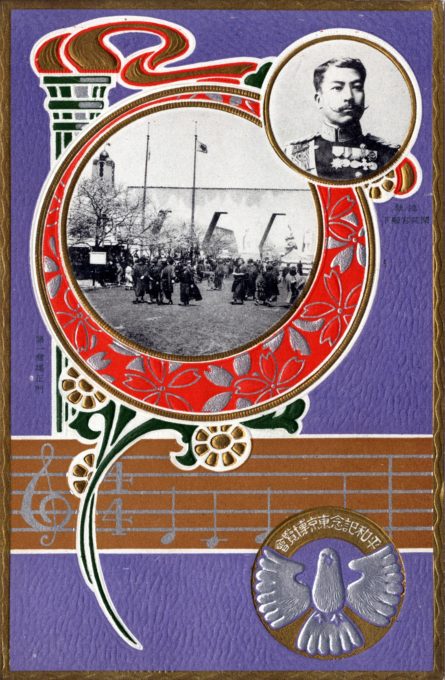

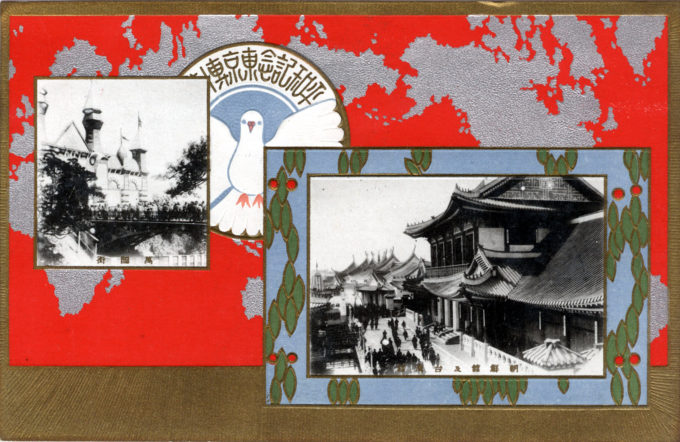

- Cover to envelope of “Commemorative Postcards for the Tokyo Peace Exposition, March 10-July 31, 1922”

- Commemorative postcard of the 1922 Peace Exposition. Photo inset is of Prince Kan’in, the festival chair.

- Back cover of envelope: Map of the exposition grounds at Ueno Park.

“[T]here is a critical interval in the 1920s, when Japan’s national flower came to symbolize something quite distinct. The Peace Exposition, which had triumphantly marked the return of Japan’s delegates from the Washington Naval Conference in 1922, had begun in March, on the eve of the annual excitement over cherry blossoms.

“As coverage of the conspicuous paean to peace began to flower, so too did the cherry trees enveloping the expo grounds in Ueno. The result was a strong new association of cherry blossoms with the 1920s culture of peace.”

– World War I and the Triumph of a New Japan, 1919-1930, by Frederick R. Dickinson, 2013

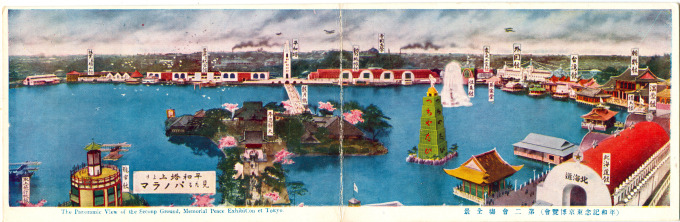

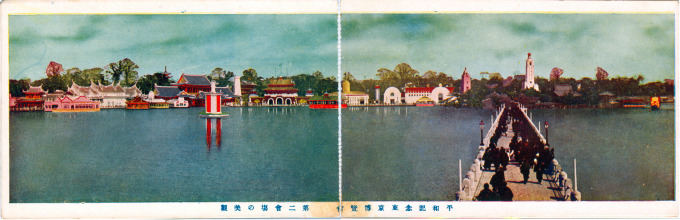

Panoramic views of the Exposition

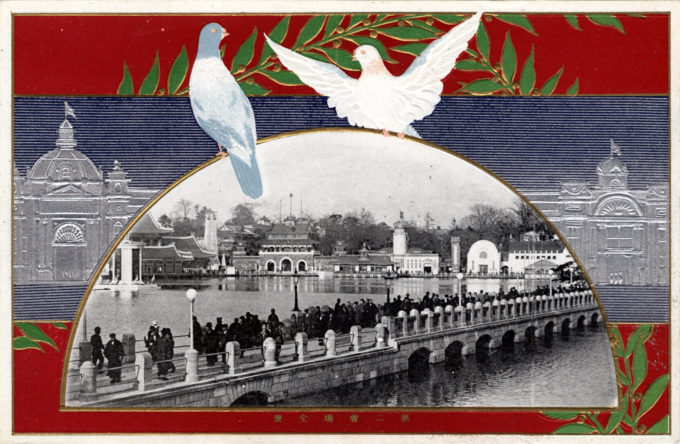

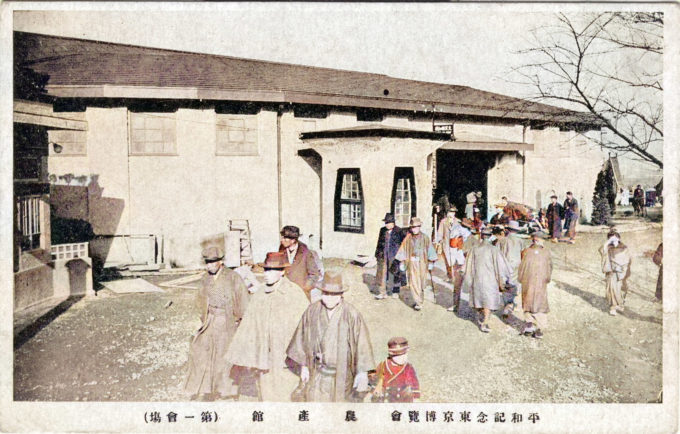

Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. A panoramic view of the 1st Section exhibition grounds, looking toward the Peace Building at center.

Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. A panoramic view of the exposition’s 2nd Section, surrounding Shinobazu Pond, which featured many of the event’s special exhibits including the Hokkaido Pavilion at lower right.

Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. Looking across Shinobazu Pond from Benten Shrine. The exposition’s Peace Tower rises to the right of the causeway.

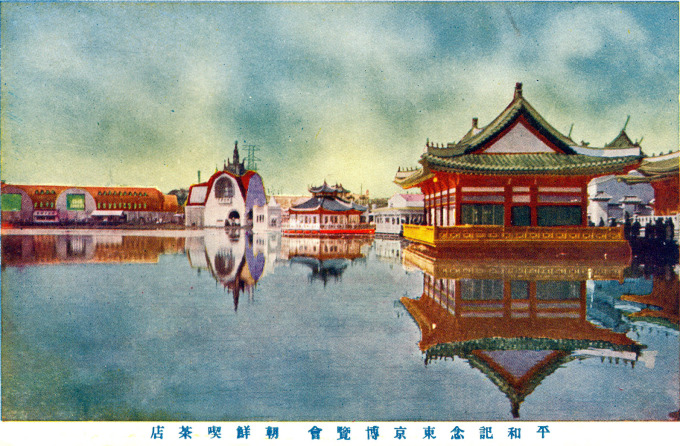

“The main center of the Exposition is the pretty little lake, in the center of which is a famous shrine to Benten, now completely overshadowed by clustering teahouses, a hanger for the hydroplanes, which never leave the surface of the water, and gaudy advertisements of beer and other daily necessities.

“On the farthest side of the lake from the entrance cluster the principal and most artistic structures, the majority being of typical Oriental architecture, but including some ornate modern halls.

“From here, around the lake, runs a wide promenade, lined on the shore side with buildings of many kinds, almost each one being an architectural oddity, with unexpected humps in the roofs and extraordinary bumps in walls. These include the machinery halls, electrical exhibit buildings and other educational displays, with dozens and dozens of other places where money can be spent.

“… The exposition covers a big space and cannot be seen in its entirety short of three or four days visits.”

– “Tokyo Peace Exhibition”, The Japan Magazine, February 1922

- 1922 Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park.

- 1922 Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park.

- 1922 Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park.

- 1922 Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park.

Exhibition Halls

International Village, Peace Commemorative Exhbition, 1922. Right-hand flag reads “South Seas” (南洋, Nan-you), identifying an exhibit for the former German colonies in the South Pacific Ocean that Japan acquired as mandates after World War I.

- Main Entrance. The five entries are hollowed out to represent the shape of Mt. Fuji.

- Heiwa-kan (Peace Hall).

- Hokkaido Pavilion.

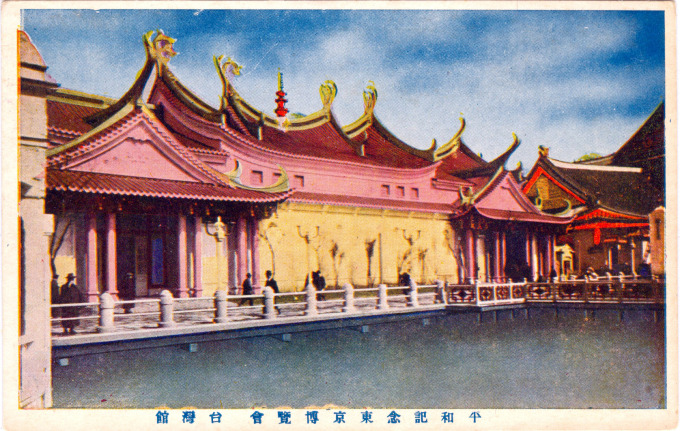

- Formosa Pavilion.

- Karafuto (Sakhalin) Building.

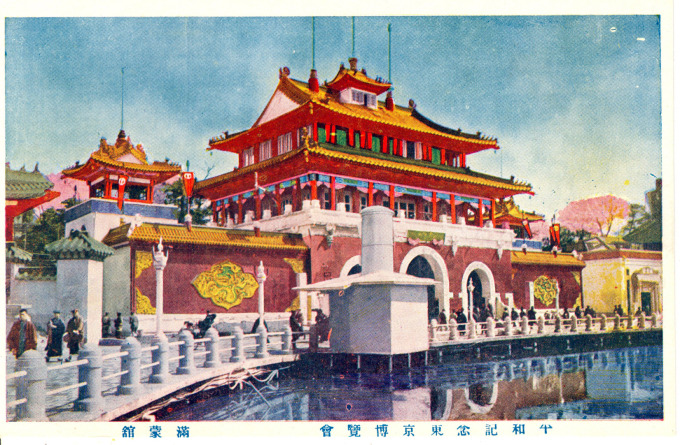

- Manchurian-Mongolian Building.

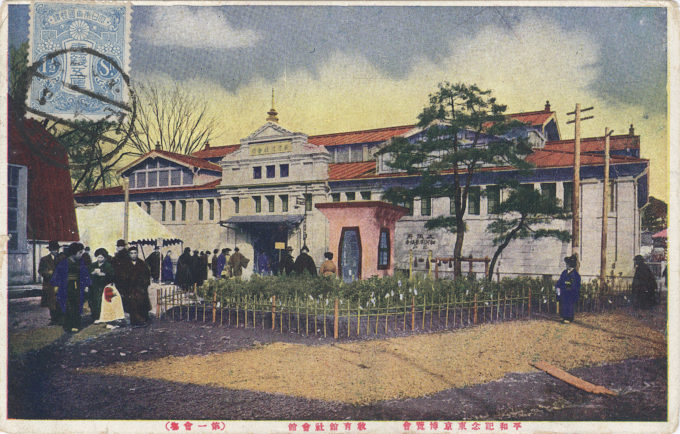

- Sanitary Building.

- Aquatic Products and Provisions Building,

- Textiles Building.

- Foreign Lands Building.

- Sumitomo Pavilion (center-left).

- Culinary Building.

- South Seas Building.

- Vegetable and Flower Garden Building.

- Education and Sports Hall.

- Sericulture Building. (Colorized)

- Agriculture Building. (Colorized)

- Overview of Shinobazu Pond. (Colorized)

Hydroplane amusement ride on Shinobazu Pond, Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. Mock-triplanes sped around Shinobazu Pond (without taking to the air) thrilling spectators and carrying thrill-seeking fairgoers.

“In the public park of Ueno the Universal Peace Exposition hums its merriest. A multicolored crowd throngs about strange edifices which combine all styles of architecture and house the most diverse wares.

“But for the public the chief attraction is to be found on the pond of Ueno … All day long three noisy machines go spluttering back and forth across it while the crowd stares in amazement; these are the hydroplanes.

Hydroplane amusement ride on Shinobazu Pond, Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. (Colorized)

“Thirty passengers can be accomodated in each, sitting in a spacious car supported on floats. On each side are canvas wings, small enough so that there is no danger of flying away. The propeller whirls at terrific speed and makes a tremendous roar, and the machine moves forward – but not fast enough to overtake the black swans on the water; the motor is six horse-power and no more.

“Tickets cost ten sen. For that modest price one hears astounded the terrific back-firing which preludes the departure; then before the eyes of all one makes a tour of the pond, and one disembarks at last, laughing, one’s ears still deafened and utterly convinced that one has gone aloft in an airplane.

“For most of the visitors this is the most beautiful memory of the Exposition.”

– The Honorable Picnic, by Thomas Raucat, 1924

Pingback: Meiji Industrial Exhibition, Ueno Park, 1907 | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Exposition of Shining Technology (2,600th National Foundation Anniversary), 1940. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Oscar V. Babcock in the 'Death Trap Loop and Flume', Peace Commemorative Exposition, Tokyo, 1922. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Ueno Park, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Taisho Exhibition, Ueno Park, 1914. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Japan Electrical Exhibition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1918. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Lotus Flower at Shinobazu Pond, Ueno, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “Culture Village”, Peace Commemorative Exposition, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1922. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Tokyo Exposition for Domestic Industry Promotion in Commemoration of the Great Coronation, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1928. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Viscount Shibusawa Eiichi, “Father of Japanese Capitalism”, various postcards, c. 1907-1928. | Old Tokyo