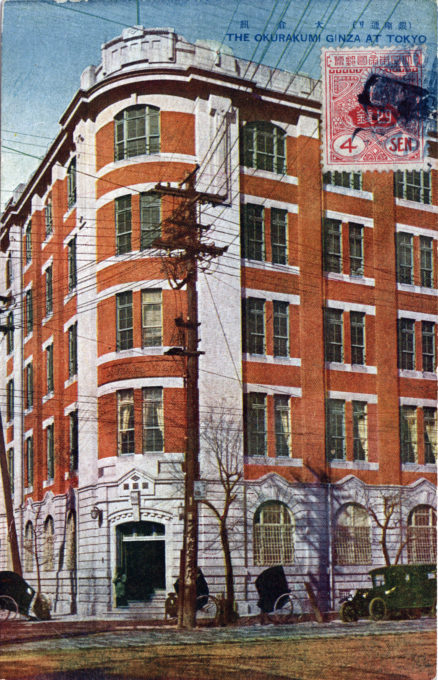

“The Okurakumi, Ginza,” 1921. The Okura Partners company headquarters, completed in 1915, replaced an earlier building on the site dating back to Okura Gumi’s incorporation during the “Ginza Brick Street restoration project” (1873-1876) funded by the government following the Ginza Fire of 1872. This building (pictured) would be replaced in 1965.

See also:

Okura Shukokwan (Okura Museum), c. 1920

Hotel Okura, c. 1970

Kawana Hotel, Izu, Shizuoka, c. 1960

Imperial Hotel (1890-1922)

“At eighty-five, Baron Okura is still strong and active. In Japan, men not only live to ripe old age but usually die in harness.

“Being a second son, Baron [Kihachiro] Okura ran away from home when he was a boy and his first work was as coolie on the docks at Yokohama. Afterwards, he became a fishmonger. In those days – the 1850’s – every alien was looked upon as a foreign devil. Okura was shrewd enough to see that in these despised ones lay the business hope of his country. As soon as he heard about guns and ammunition, he decided that they would be the best articles for him to deal in, so he began a more or less surreptitious trade in them. On account of his negotiations with foreigners, two attempts were made to assassinate him.

“With the overthrow of the Shogunate in 1867, Okura became an army contractor. He realized that the cotton uniforms were of no service, so in 1872 he visited America and brought back samples of woolen clothes which he introduced into the Japanese army. With them he laid the foundation of his fortune, because he then started the great firm of Okura & Co. which is today a strong competitor of Mitsui & Co. and Suzuki & Co., the leading import and export firms. Baron Okura is not only the active head of Okura & Co. but is chairman of the board director or auditor of forty-five other corporations which include practically every important financial or productive activity in Japan.

“I went to see him at the headquarters, Okura & Co., which are in a big building on the Ginza, the leading thoroughfare of Tokio. The baron wore a simple black kimono with the family crest embroidered in white on the sleeves. He speaks no English; our conversation was carried on through his son [Kishichiro] who studied at Cambridge and who will succeed him as head of the house.

“… Like many other Japanese, Baron Okura’s hobby is penmanship. This means that he takes delight in writing the Japanese ideographs in which great artistic skill may be developed. Over his desk hangs one of his favorite mottoes, which he has written in Japanese with such precision that it looks like a work of art. Translated it reads:

‘One need not bequeath fortune to one’s descendants,

as they have their own fortune to make by themselves.’ “– ‘The Changing East’, The Saturday Evening Post, September 16, 1922

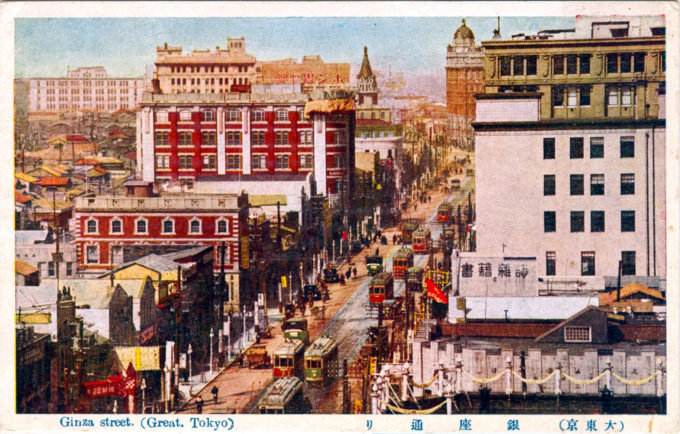

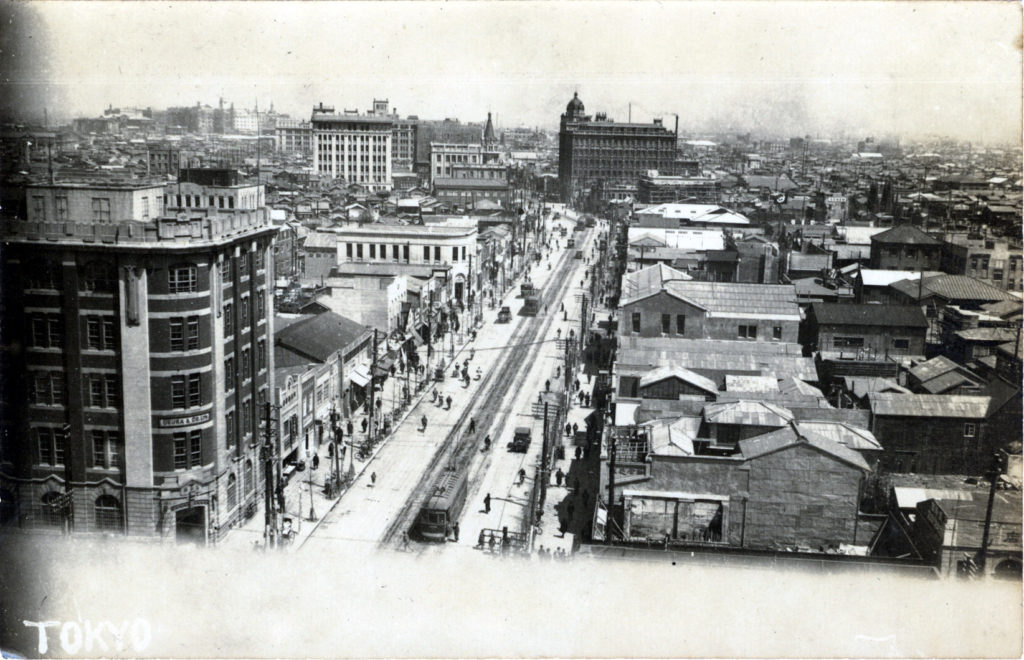

The Okura Kumi headquarters (left) from the roof of the Matsuya department store, c. 1930. In the distance is the Dai-ichi Sogo building at Kyobashi. In contrast to most of the zaibatsu (literally, “financial clique”; industrial conglomerate), the Ōkura zaibatsu was founded by someone from the peasant class. Kihachiro Ōkura moved from what is now Niigata Prefecture on the north shore of Honshū to Edo and worked for three years before starting his own grocery store in the 1850s. After selling groceries for eight years, he became a weapons dealer during the turbulent years between the arrival of Commodore Perry’s Black Ships (in 1853-54) and the eventual overthrow in 1867 of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

“While Andrew Carnegie gives out libraries, the Baron Kihachiro Okura endows commercial colleges; and whereas the one is founder of the Carnegie Foundation, the other shares with the Emperor in the support of the Imperial Charitable Society; one made his money in iron and steel, and the other in arms and ammunition. But, for all these differences, there seem to be some rounds for identifying these two men and for calling the latter as they do in his own country, ‘The Carnegie of Japan’.

“Looking down the city from the roof of Matsuya”, Tokyo, c. 1930. The Okura Kumi building can be seen at left-center.

“Baron Okura, who now proudly bears the Second Order of the Rising Sun and is a Junior of the Fifth Grade in court rank, began his independent career in a dried-fish shop. Before that, he was apprentice to a pawnbroker. Such a start is familiar in the lives of our American captains of industry, and for a Japanese to start so and to attain the eminence of Okura is a proof of the permeation of Western democratic standards into Japanese life. An idea of the position he now occupies in Japan may be gained from the list of activities gleaned from Who’s Who in Japan

“… We are told that Baron Okura takes great personal care of his health always insisting on seven hours sleep every day. Once a day he insists on having broiled eels with rice called unagimeshi. He is a man of cheerful temperament and robust constitution; and though now 79, he does not seem an old man.

“Baron Okura is fond of art and has a taste for vocal music and poetry. His one motto in life is ‘self independence for every man.’ He holds that every hard worker is certain to gain independence. He says that he has lived that motto and proved its truth. He does not believe in speculation as such, and has never engaged in it. He does not believe in saving money to leave to children to spend in self indulgence, and has brought up his own children after this principle.”

– “An Oriental ‘Andy'”, The Literary Digest, March 25, 1916

- Okura Building (red building left of center) at Kyobashi, c. 1920.

- Okura Building (left), Kyobashi, c. 1930.