See also:

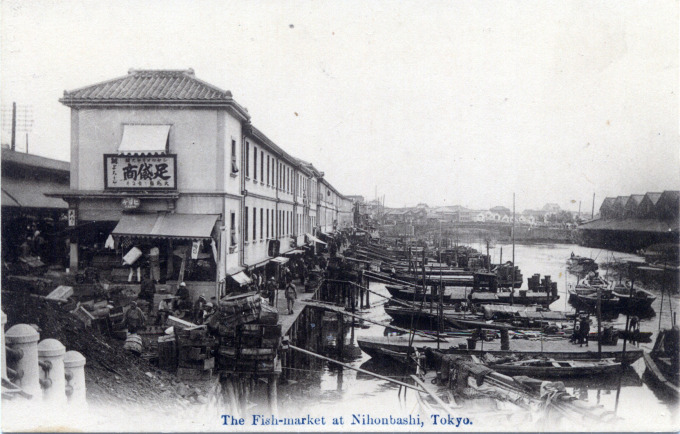

Uogashi (Fish Market) at Nihonbashi, c. 1910

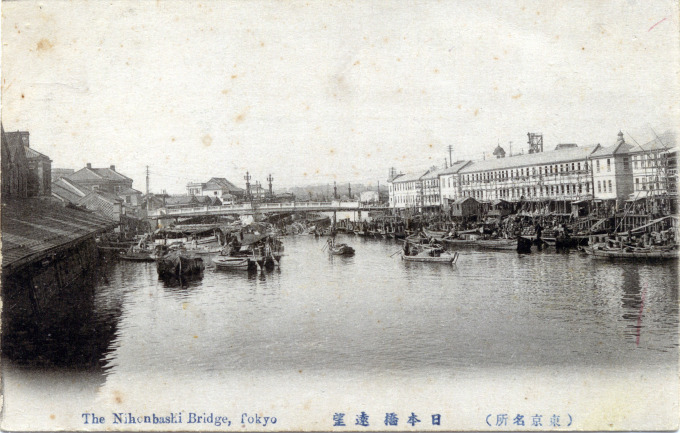

Nihonbashi Bridge

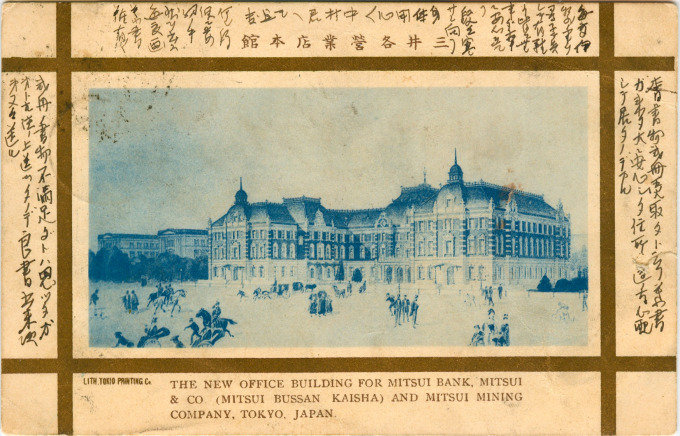

Mitsukoshi Department Store, c. 1903-1923

“The new neighborhoods flourished as part of an integral part of the commercial center of Edo that ran from Hon-cho through Nihonbashi south to Nakabashi and Kyobashi.

“The four quarters were fortuitously located, adjacent to Nihonbashi Bridge, terminus for the great Tokaido highway. But even more important … people and commodities moved on water in early Edo.

“The Nihonbashi and Kanda rivers constituted key links in an extensive network of waterways that tied the city together, and it is small wonder that the wharfs of Yokkaichi-cho and Zaimoku-cho become busy transshipment points for goods arriving by sea or that flourishing rice and fish markets could be found on the northern bank of the Nihonbashi River.”

– Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era, edited by James L. McClain, John M. Merriman, Kaoru Ugawa, 1997

“In 1889 the fish market‘s location became an urban planning issue. Tokyo officials sought to remove the market from the commercial heart of the modernizing city. The unseemliness of a messy, smelly marketplace in the center of the city’s financial district – outside the windows of the new Bank of Japan – offended Meiji bureaucratic sensibilities, and officials argued for relocation on the grounds of sanitation, public health, and the logistical difficulties of transportation around Nihonbashi.

“Many Nihonbashi fish merchants stoutly resisted pressure from the Tokyo municipal government to move, and proposals to relocate the marketplace were delayed, derailed, or debated to a standstill again and again.

“… The issue was settled – as if by a deus ex machina – on September 1, 1923, when the Kanto earthquake struck the city just before noon, when cooking fires were alight everywhere.”

– Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World, by Theodore C. Bestor, 2004

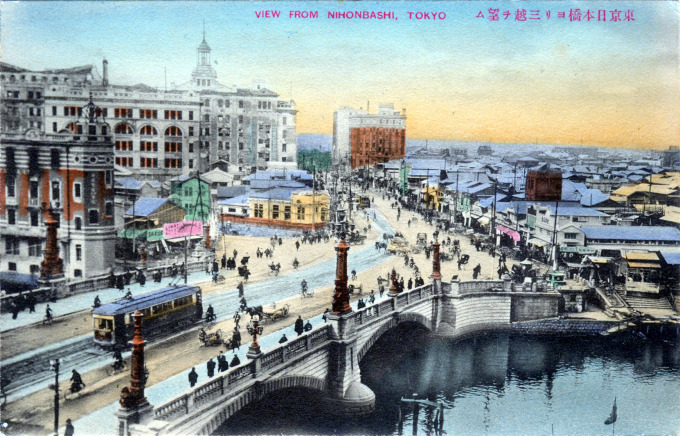

At the dawn of the 20th century, the Nihonbashi [Japan bridge] district (named for Japan’s most prominent bridge from which all distances in the country were measured) still had a marketplace atmosphere about it. The presence of canal-side warehouses, shophouses, and fish markets, important purveyors of goods and services during the Tokugawa era, would remain until the last of the fishmongers were relocated to Tsukiji following the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake.

The district gained Imperial and artistocratic financial importance when, after the completion of the Nippon Ginko [Bank of Japan] in 1896, the national mint was moved to Nihonbashi. Other, private banks had already located head offices in Nihonbashi including Mitsui (in 1876), Dai-ichi Sogo, Sumitomo, Yasuda and the Yokohama Specie Bank. The Tokyo Stock Exchange opened for securities and equities trading in 1878 near the Yoroi bridge.

- Bank of Japan, street view, c. 1910.

- Mitsui Bank at Nihonbashi, c. 1905.

More domestic needs were accommodated on each side of Nihonbashi bridge at two fashionable department stores, Mitsukoshi Gofukuten and Shirokiya. As in all of Tokyo’s neighborhoods, numerous small shrines and temples dotted the backstreets. Within Nihonbashi’s Ningyo-cho [doll district] mothers-to-be could visit Suitengu Shrine where they received protective amulets for their unborn, and long strips of blessed white cotton to wrap around their stomach for good health and protection.

- Nihonbashi Bridge, elevated tinted view north toward Mitsukoshi department store, c. 1920.

- Looking south from Nihonbashi toward Ginza, c. 1910.

- In the distance is the Tokyo Stock Exchange at Kabujocho in the Nihonbashi district, c. 1910.

- Nihonbashi residential area, looking toward the Sumida River from Mitsukoshi department store rooftop, c. 1920.

Pingback: Horse-drawn trolley, Nihonbashi, Tokyo, c. 1900. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Uogashi (Fish Market) at Nihonbashi, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Mitsui Bank, Nihonbashi, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo