“Although in the early days officials discouraged settlers who had passed the prime of life, in an article published in 1942, emigrants were exhorted to ‘take the old folks with them’ to help with this second generation. ‘The birth rate among settlers is high but the incidence of miscarriage, premature birth, and infant mortality is also high. For the most part this appears to be caused by the fact that these are first births and that there is a shortage of experienced people around to help. If the grandparents were available their experience would save not only the family but the whole village from disaster.’

“Thus, the presence of women, children, and grandparents in the imagined imperial landscape reflected the new sense of intimacy with which the Japanese now regarded Manchukuo. In this sense the idea of racial expansionism implied the Japanizing of Manchuria both literally and metaphorically. Transplanting entire households to the new empire raised the Japanese percentage of the population. At the same time, the projection of images of motherhood and connubial life domesticated the empire.”

– Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, by Louise Young, 1999

From the wiki: “During the 1920s, the Japanese Army under the influence of the Wehrstaat (Defense State) theories popular with the [German] Reichswehr had started to advocate their own version of the Wehrstaat, the totalitarian ‘national defense state’ which would mobilize an entire society for war in peacetime. An additional influence on the Japanese ‘total war’ school who tended to be very anti-capitalist was the First Five-Year Plan in the Soviet Union, which provided an example of rapid industrial growth achieved without capitalism.

“At least part of the reason why the Kwangtung Army seized Manchuria in 1931 was to use it as an laboratory for creating an economic system geared towards the ‘national defense state’; colonial Manchuria offered up possibilities for the army carrying out drastic economic changes that were not possible in Japan. From the beginning, the Army intended to turn Manchukuo into the industrial heartland of the empire, and starting in 1932, the Army sponsored a policy of forced industrialization.

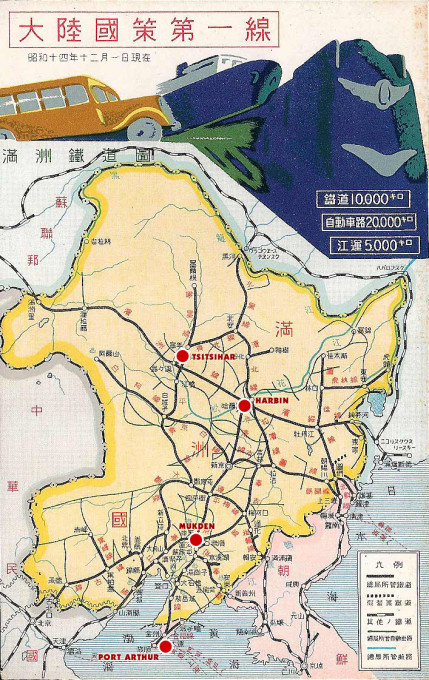

Manchukuo (Manchuria), c. 1940, and the major railways and roads connecting its four largest population centers – Port Arthur, Mukden (the largest), Harbin, and Tsitsihar – and its capital city, Hsingching [‘New Capital’, between Harbin & Mukden; now, Changchun] to the various areas of development in the colony.

“Reflecting their dislike of capitalism, the Zaibatsu were excluded from Manchukuo and all of the heavy industrial factories were built and owned by Army-owned corporations. ‘Reform bureaucrat’ Nobusuke Kishi persuaded the Army to allow the zaibatsu to invest in Manchukuo, arguing that having the state carry out the entire industrialization of Manchukuo was costing too much money. Kishi pioneered an etatist system where bureaucrats such as himself developed economic plans, which the zaibatsu had to then carry out. American historian Mark Driscoll described Kishi’s system as a ‘necropolitical’ system where the Chinese workers were literally treated as dehumanized cogs within a ‘vast industrial machine’. The system that Kishi pioneered in Manchuria, of a state-guided economy where corporations made their investments on government orders, later served as the model for Japan’s post-1945 development, albeit not with same level of brutal exploitation as in Manchukuo.

“By the 1930s, Manchukuo’s industrial system was among the most advanced making it one of the industrial powerhouses in the region. Manchukuo’s steel production exceeded Japan’s in the late 1930s. Many Manchurian cities were modernized during Manchukuo era. However, much of the country’s economy was often subordinated to Japanese interests and, during the war, raw material flowed into Japan to support the war effort. Traditional lands were taken and redistributed to Japanese farmers with local farmers relocated and forced into collective farming units over smaller areas of land.”

“Born as a by-product of Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 to 1905, Mantetsu [Minami Manshu Tetsudo Kabushiki-kaisha, ‘South Manchurian Railway Company‘] had a profound economic and political impact on the region’s development and the outcome of World War II in Asia. The 40-year history of the Mantetsu fascinates not only Japanese historians but also the general public, partly because of the image that Japanese were building a new semi-autonomous state outside of Japan.

“More than 1 million Japanese civilians migrated to Manchuria to begin a new life in better economic conditions. They had a western colonial lifestyle, enjoying golf clubs, large parks, and western style housing. The special [American-built] express trains called ‘Asia’ were among the fastest, best appointed trains in the world. The capital of Manchukuo, Hsinching (now Changchun), was built with modern urban planning with avenues and streets akin to Paris.

“In 1937, the Mantetsu owned 15 companies, 32 subsidiary companies, and invested in 33 more companies. They operated transport (rails, shipping, and airline), industry (steel mill, chemical, oil refinery, cement, textile, sugar), commerce (trading, retail), construction, lumber, minerals (coal and gold), electric and gas power, real estate, telecommunication and the press, and hotel chains. By its end, the Mantetsu ran or owned 71 companies with 340,000 employees, including 248,000 Chinese and Russians.”

– From a review by Fumiko Halloran of The Comprehensive History of South Manchurian Railways Company, by Kiyofumi Kato, 2006

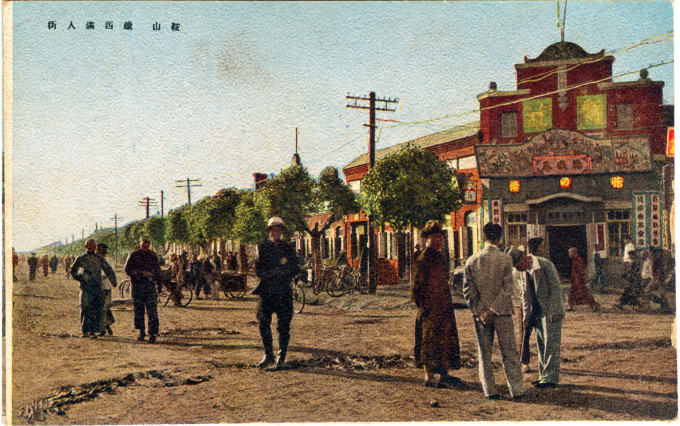

- Street scene, Manchukuo, c. 1940.

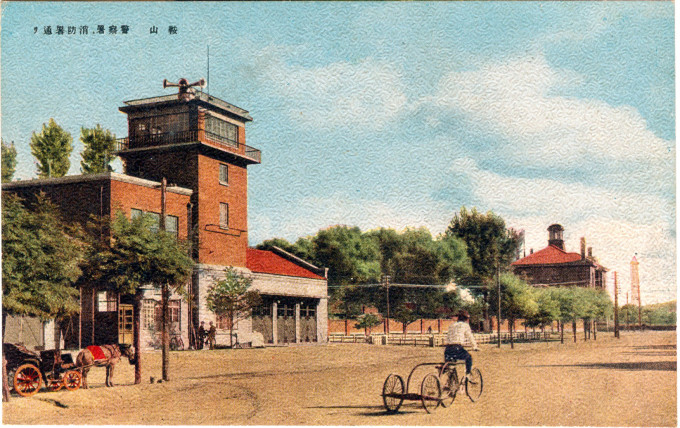

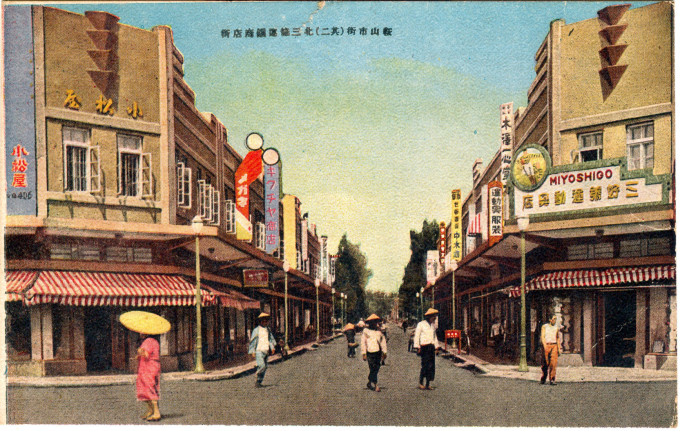

- Street scene, Manchukuo, c. 1940.

Pingback: Patriotic Youth Brigade Farmers propaganda postcard, Manchukuo, c. 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Yamato Hotel, Dairen, Manchuria, c. 1930. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo