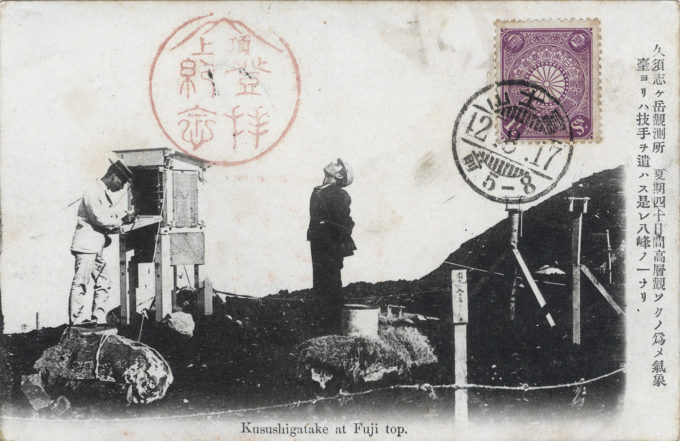

Kusushigatake Observatory meteorological station, Mt. Fuji, 1937. “Kusushigatake” refers to one of the eight peaks, the hachiyo (eight petals), surrounding Mt. Fuji’s volcanic crater. Each peak’s name is associated with Buddha’s hachiyo kuson (eight-petaled lotus). The caption reads “The summer season is [only] forty days of high-altitude observation, so you must use your skills to the utmost for weather observation.”

“It was on August 1, 1932 that Japan’s Central Meteorological Office commissioned its first officially funded observatory on Mt Fuji. Gathered round the small summit hut almost four kilometres above sea-level the weathermen must have felt themselves as far above the era’s murky politics and foreign policy as ‘clouds from mud’. [T]he government had seen fit to approve just one year of continuous weather observations atop Mt Fuji, as part of Japan’s contribution to the Second International Polar Year in 1932-33.

“As a single year’s weather readings would be scientifically of little worth, the government’s stinginess made no sense to the weathermen. So, in mid-December 1933, when the last approved summit crew were ordered to bring down the portable gear after they finished their month-long shift, they fell to plotting. How would it be, they mused, if they just sat out the winter in the summit hut, continuing their work in a kind of high-altitude sit-in strike.

“The team leader – not to say ring leader – in this enterprise was Fujimura Ikuo, who later went on to head up the observatory in a meteorological career spanning three decades. At first, he and his crew cast about for some plausible-sounding pretexts for disobeying their orders – for instance, the slopes would be too icy to let them bring down delicate instruments, and so they’d have to stay on at the summit to look after the kit.

“In the event, they made no such excuses. On arriving at the summit, they simply told the outgoing shift that they would stay until summer and keep up the observations. With that, Fujimura handed over a missive to the Meteorological Office’s directors and, together with his rebel crew, shut himself up for the winter. Fortunately, his resolve wasn’t put to the test. On New Year’s Eve, a telegram arrived from Fujimura’s superiors: ‘Observations temporarily extended; you are instructed to descend when relief crew arrives.’

“The following September, the funding crisis was eased when a foundation set up by the Mitsui zaibatsu stumped up seven thousand yen. A year later, in October 1935, the government switched the summit station’s funding to the regular budget, so that it could continue operating indefinitely.

“… On March 13, 1945, one of the weathermen climbed the observation tower above the hut and, looking westwards in the direction of Nagoya, saw a reddish glow in the sky, beyond the shoulder of Akaishi-dake. Soon the spectacle would be repeated, and in almost all quadrants of the compass. Feelings of despair overcame the summit crews as, night after night, they watched these false dawns.”

– “Mt. Fuji at War: How Japan’s mountain-top meteorologists rode out the dark years of early Shōwa”, Published by Project Hyakumeizan, One Hundred Mountains, 2014