See also:

Uogashi (Fish Market) at Nihonbashi, c. 1910.

“One of the attractions of the island for Tokyo residents through the years has been the odor of soy sauce permeating the air on Tsukudajima, for the fisherman developed a culinary delight by simmering fish in seaweed and soy sauce. Preserved in this boiled-down sauce along with salt, tsukudani became a much-desired delicacy.”

– Tokyo: A Cultural Guide to Japan’s Capital City, by John Martin & Phyllis Martin, 2013

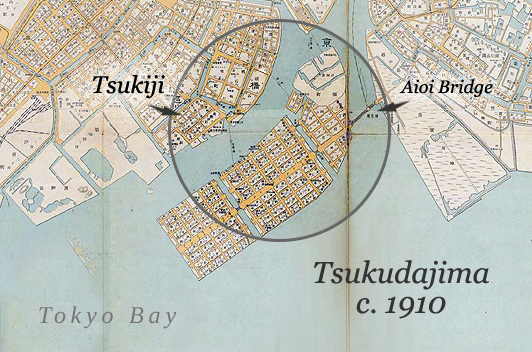

Aioi-bashi, connecting Tsukudajima with the mainland at Fukugawa , c. 1910. By this time, life on the island was evolving from seafaring to warehousing.

Tsukudajima was one of two islands formed at the mouth of the Sumidagawa (the other being Tsukishima). It was given its name by the first Tokugawa shogun, Ieyasu, after he issued a special decree moving thirty-three specialist shiraou [whitefish] fishermen to the island from the village of Tsukudama, near Osaka. The fishermen brought with them the cult of the Sumiyoshi deity, the protector of seafarers. In return for exclusive fishing rights to the waters of upper Edo Bay, the fishermen supplied Ieyasu’s court with fish – in particular, the first catches of shiraou each winter.

The fishermen were also allowed to sell their excess catch on the quay at the fish markets at Nihonbashi, becoming the first proprietors of what would become the Tsukiji fish market, across from Tsukudajima, after 1923. One of the island’s culinary attractions was a delight the fishermen created by simmering shiraou in soy sauce and seaweed, tsukuda-ni. And, as excellent watermen and navigators, the fishermen also served another purpose for the shogun: they could recognize any strange boats in the bay and warn the shogun of any potential hostile threats.

During the Meiji era, the fishermen of Tsukudajima were gradually squeezed out as the island became the site of warehouses, for goods on- and off-loaded from tall-masted sailing ships, and small manufacturers, including a dry ice factory. But, some of the old communities survived well into the 20th century. Physically isolated from the mainland and surrounded by water, Tsukudajima managed to escape the destruction of both the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake and the 1945 wartime firebombings of Tokyo, and many Meiji-era residences still existed there until the 1980s.