See also:

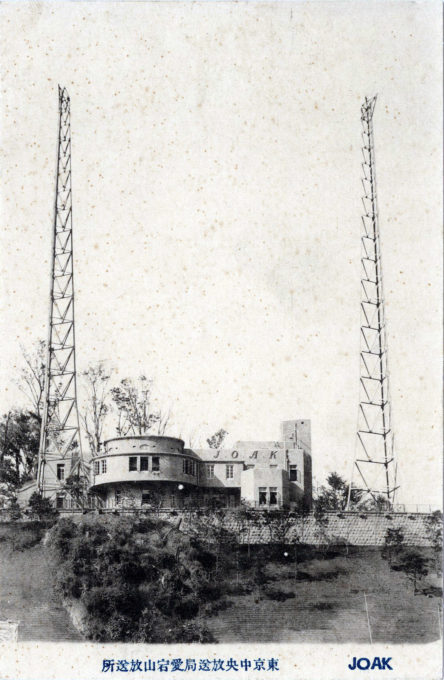

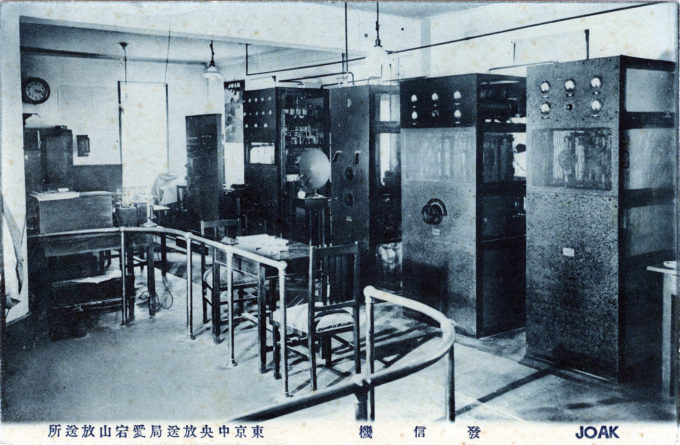

The Tokyo Broadcasting Office (JOAK), Atago Hill, Tokyo, c. 1925.

JOBK (NHK) Radio, Osaka, 1926.

Atagoyama (Atago Hill), Tokyo, c. 1910-30.

“On the evening of August 13, 1925, the Tokyo Broadcasting Station (call sign JOAK) broadcast a radio drama entitled Tanko no naka (In a Coal Mine). Although it wasn’t the first radio play ever to be broadcast in Japan, it was the first to be designated as a radio drama (rajio dorama), as opposed to a radio play (rajio geki) or some other name.

“Tanko no naka was a translation by playwright and director Osanai Kaoru of a radio drama entitled Danger … produced by Nigel Playfair for the BBC. That radio piece had had its premier in London on January 15, 1924, and is widely considered the first play written in the United Kingdom specifically for the medium of radio.

“Danger is set in a coal mine in Wales. A young couple, Jack and Mary, and an old man, Mr. Bax, find themselves lost in a coal mine after an electrical failure. Since the action is set in complete darkness, the announcers introducing the play for both the London and the Tokyo broadcasts advised their respective audiences to turn off their lights as they listened in.

“Tokyo Broadcasting Station at the time was housed in a building in central Tokyo, atop a twenty-six-meter-high hill called Atagoyama with an impressive view of the surrounding streets and buildings. Producer Kobayashi Tokujiro later recalled that after the announcer had finished his introduction, ‘if you looked outside the window, you could see the lights in the houses down below going off one by one.’ A magazine reporter present during the broadcast wrote that there was ‘an unusual tension in the air, like Paris bracing itself for a night attack from a German Zeppelin. All the homes listening to the radio were shrouded in darkness.'”

– Electrified Voices: How the Telephone, Phonograph, and Radio Shaped Modern Japan, 1868-1945, by Kerim Yasar, 2018

“It wasn’t long before the need for sound effects became apparent. According to Yamato, the July 19, 1925, broadcast of Taii no musume (‘The Captain’s Daughter’), adapted from the novel Gendarm Mobius by the German poet and novelist Victor Bluthgen, was the first work produced for the radio that called for a sound effect – in this case, a fire bell.

“The producer of the broadcast looked around for an acceptable approximation and wound up using a real fire bell. Because the studio was small and the sound of a real bell would be too loud for the microphone to pick up properly, the stage assistants opened the door of the studio and rang the bell as they walked through the hall. The sound of the fire bell thus escaped in the surrounding area, and alarmed neighbors called the fire department.

“Later experiments revealed that banging the rim of a kettle was an even better approximation than the real thing for the purposes of radio. Yamato Sadaji suggests that this episode revealed two of the fundamental challgenges of sound effects, which persist to this day: First, the sound of the real thing often does not sound like the real thing when broacast or recorded; and second, it’s often difficult to gauge the right amount of distance to place between the sound source and the microphone.

“… The production [of Tanko no naka, in August,] called for a number of [other] different sound effects: The sound of a pickax was created by striking together two storm door rollers; the explosion in the coal mine was represented by striking piano wires and a kettle drum; and the sound of the mine flooding was created by loosening the cap of a gas cylinder in a tub full of water. The echoes one would imagine being produced in a coal mine were approximated by positioning two large taiko drums next to the microphone, a method that was arrived at through a long process of trial and error.”

“… In February 1936 JOAK established a Gion kenkyukai (sound effects research group), which met every Tuesday and Friday. Kimura Hajime taught the younger effects technicians about the fundamentals, and the group also explored and experimented with new possibilities … By 1937 Japanese sound-effects technicians were producing their own sound-effects records.

“All this suggests that the real hotbed of sound-effects innovation in Japan in the late 1920s and 1930s was radio. In that sightless medium, anything that doesn’t sound in effect doesn’t exist; it can be referred to, but if no sound is ascribed to it, it has no presence. This is obviously very different from cinema, where things generally have a presence by being visible.

“… Sound-effects know-how did transfer between radio specialists and film specialists, but the transfer was not very extensive. The institutional structures of the two industries made the sharing of personnel unusual (though not impossible), and the techniques developed by individual groups were considered proprietary knowledge jealously guarded from both other industires and competitors in the same industry. Thus, even though Tokyo JOAK and Osaka’s JOBK were united under the NHK umbrella and didn’t compete for the same audience, the effects technicians at one station didn’t share their most recent inventions with their colleagues at the other station.”

– Electrified Voices: How the Telephone, Phonograph, and Radio Shaped Modern Japan, 1868-1945, by Kerim Yasar, 2018