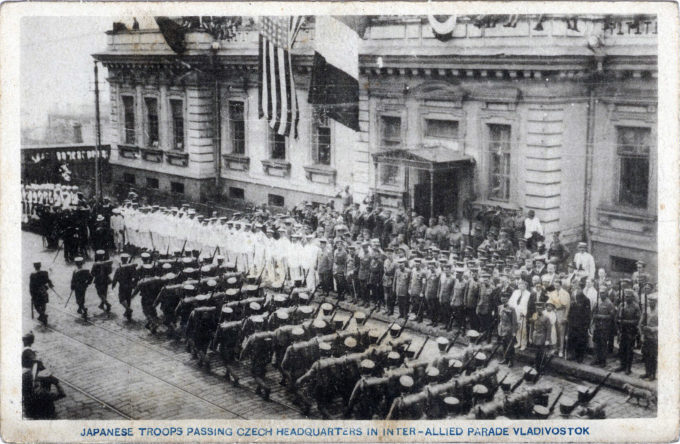

“Japanese troops passing Czech [Legion] headquarters in inter-Allied parade”, Vladisvostok, Russia, c. 1920. The Japanese Siberian Intervention (Shiberia shuppei) of 1918–1922 was the part of a larger effort by the western Entente (Allied) powers, along with Japan, to support White Russian forces against the Bolshevik Red Army during the Russian Civil War, and the “rescue” of the Czech Legion. The Japanese eventually deployed 70,000 troops. The last of the retreating Czech Legionnaires arrived in Vladivostok in July 1920.

See also:

Siberian Intervention commemorative postcard, c. 1920.

“[C]onditions in Siberia were going from bad to worse.

“The Bolsheviki were everywhere fraternizing with German and Austrian prisoners of war whom they had released … The number of liberated war prisoners in that region was estimated variously between 30,000 to 60,000.

“At that critical period a new and important factor was injected into the Siberian situation in the advent of a large number of Czecho-Slovaks who came into collision with the Bolsheviki and their German [POW] allies.

“These Czecho-Slovaks were originally part of the Austrian army. They had, fifty thousand strong, deserted Austria and joined the Czarist Russian army at the eastern front, intending to help defeat the Central Powers with the hope of securing the independence of their native land [from the Austro-Hungarian Empire].

“When Russia collapsed under the Bolshevik regime, the Czecho-Slovaks took possession of Siberian trains and moved eastward with the intention of going to the western front [to fight Germany] by reaching Vladivostok and sailing across the Pacific Ocean and sailing across the Pacific Ocean to reach Europe by way of America. By the summer of 1918 many of these Czecho-Slovaks reached eastern Siberia, and there engaged the Bolsheviki and [liberated] Germans in fighting.

“With the advent of these soldiers, alien to Russian soil, [U.S.] President Wilson saw a gleam of hope for restoring order in Siberia. In June, 1918, Mr. Wilson began to negotiate with Japan with a view to sending a Japanese-American force to Siberia for the aid of the Czecho-Slovaks.”

– Japan and World Peace, by K.K. Kawakami, 1919

Pingback: Siberian Intervention commemorative postcard, c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo