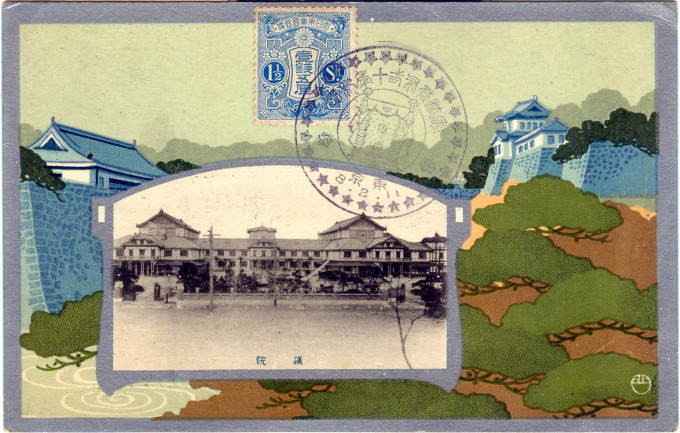

The second Imperial Diet Building (1891-1925), near Hibiya Park, similar in design to the first Diet which was destroyed by an electrical fire shortly after completion in 1890.

See also:

Kasumigaseki (Government District), c. 1910

Justice Ministry, Kasumigaseki, c. 1910

Taishin-in (Supreme Court), c. 1910

Josiah Conder: Department of the Navy, Kasumigaseki, c. 1910

“From the time of the earliest stages of planning in the 1880s, people recognized the future Diet Building’s potential to represent a vision of Japanese national identity both domestically and internationally. Yet no consensus was ever reached on how the Diet could most effectively fulfill that role.

“The protracted debates over the Diet’s design testify to the complex cultural contradictions generated by the process of appropriation through which Western ideas were incorporated into Japan as part of the ambitious project of modernization.”

– Japan’s Imperial Diet Building: Debate over Construction of a National Identity, Jonathan M. Reynolds, Art Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1996

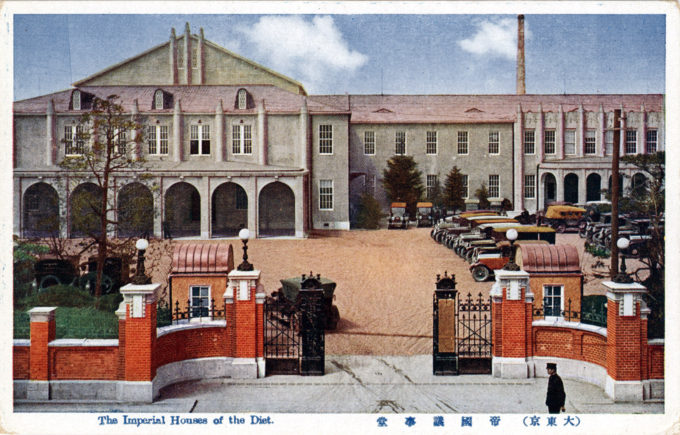

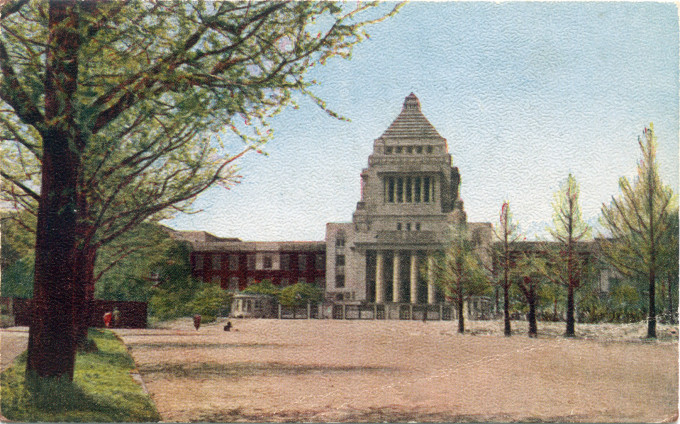

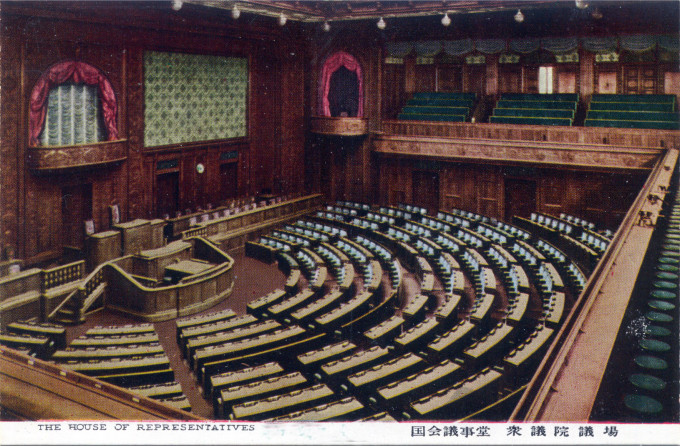

House of Representatives (Diet), Tokyo, c. 1920. Imperial Diet sessions were held in this building (the second Diet) 48 times before it burned down in 1925. A third Diet was rushed to completion in only 80 days, and served as a temporary site until 1936 when the long-planned present-day structure, the fourth Diet, was completed.

“Japan’s first modern legislature was the Imperial Diet established by the Meiji Constitution in force from 1889 to 1947. The Meiji Constitution was adopted on February 11, 1889 and the Imperial Diet first met on November 29, 1890 when the document entered into operation. The Diet consisted of a House of Representatives and a House of Peers. The House of Representatives was directly elected, if on a limited franchise; universal adult male suffrage was introduced in 1925. The House of Peers, much like the British House of Lords, consisted of high ranking nobles.

“The word Diet derives from Latin and was a common name for an assembly in medieval Germany. The Meiji constitution was largely based on the form of constitutional monarchy found in nineteenth century Prussia and the new Diet was modeled partly on the German Reichstag and partly on the British Westminster system.

Exterior views, Imperial Diet Building (1891-1925)

- Diet, House of Representatives, c. 1910.

- Diet, House of Peers, c. 1910.

“The construction of the building that would become today’s Diet building began in 1920; however, plans for a Diet building date back to the late 1880s when German architects Wilhelm Böckmann and Hermann Ende were invited to Tokyo in 1886 and 1887, respectively, on the eve of the Meiji Constitution promulgation in 1889. Böckmann’s initial plan was a masonry structure with a dome and flanking wings, similar to other legislatures of the era, which would form the core of a large ‘government ring’ south of the Imperial Palace at Kasumigaseki. Ende and Böckmann’s Diet Building was never built (due to public resistance to Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru’s internationalist policies, but their other ‘government ring’ designs were used for the Tokyo District Court and Ministry of Justice buildings.

“With an internal deadline approaching, the government enlisted Ende and Böckmann associate Adolph Stegmueller and Japanese architect Yoshii Shigenori to design a temporary structure. The building, a two-story, European-style wooden structure, opened in November 1890 on a site in Hibiya. An electrical fire burned down the first building in January 1891, only two months later. Another Ende and Böckmann associate, Oscar Tietze, joined Yoshii to design its replacement.

“The second Diet (above) was larger than the first, but followed a similar design. Imperial Diet sessions were held in this building 48 times before it, too, burned down, in 1925. A third Diet was rushed to completion in only 80 days, and served as a temporary site until 1936 when the long-planned present-day structure, the fourth Diet, was completed.

“The Finance Ministry first sponsored a public design competition in 1918 for a more permanent Diet building, and 118 designs were submitted. The first prize winner, Watanabe Fukuzo, produced a design similar to that of Ende and Böckmann.

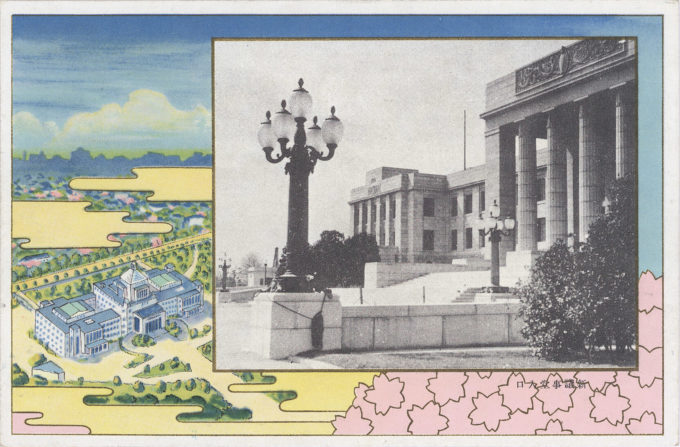

“The present-day Diet Building was eventually constructed between 1920 to 1936 across from the Imperial Palace with a floor plan based on Fukuzo’s entry. The roof and tower of the building might have been inspired by another entrant, third prize winner Takeuchi Shinshichi, and are believed to have been chosen because they reflected a more modern hybrid architecture than the purely European and East Asian designs proposed by other architects.

“While the exact source for the ‘pyramid’ roof remains unclear, Japanese historian Jonathan Reynolds suggests it was ‘probably borrowed’ from Shinshichi’s third-place design; although an image of the entry is not provided Reynolds instead thanks fellow historian of Africa studies at Columbia, Zoe Strother, for mentioning that Shinshichi’s design resembled the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus [Wikipedia] which was a model for some prominent Western designs in the early 1900s such as John Russell Pope’s 1911 award-winning House of the Temple in Washington, D.C. and the downtown Los Angeles City Hall, completed in 1928.”

– Wikipedia

“The Diet Building stands majestic and imposing in Nagata-cho, the White Hall St. of Tokyo, and its stepped white tower is seen from most parts of the city. The building is in a modified Renaissance style, with its exterior finished with white granite. Its front entrance measures 681 ft. from end to end and it is 292 ft. high. There are 393 rooms in the structure and the auditoriums of the Upper and Lower Houses are provided with 635 seats each, while the gallery has 770 seats for the Upper and 922 seats for the Lower House.

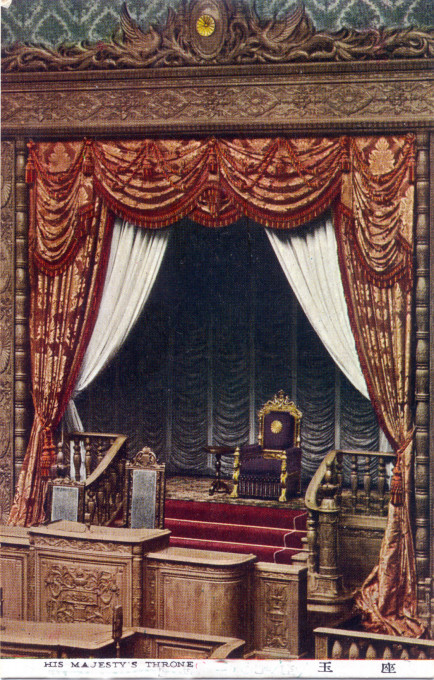

“… The materials used in the building of the Diet were brought from different parts of the country: granite and marble from Hiroshima, Kyushu and Okayama Prefecture, and lumbers from keyaki and hinoki (Japanese cypress) from many different provinces. Most decorative motifs used in the wood carvings and mouldings represent ancient Japanese folklore and mythologies, the phoenix in bas-relief being the Japanese symbol for eternity.”

– We Japanese, Vol. 2, Sakai Atsuharu, Fujiya Hotel, 1937

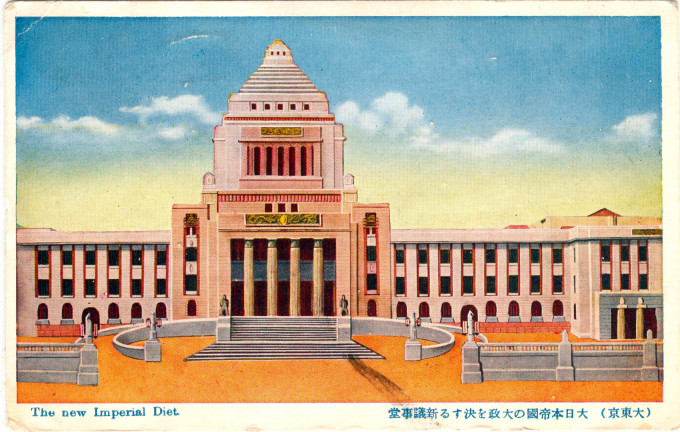

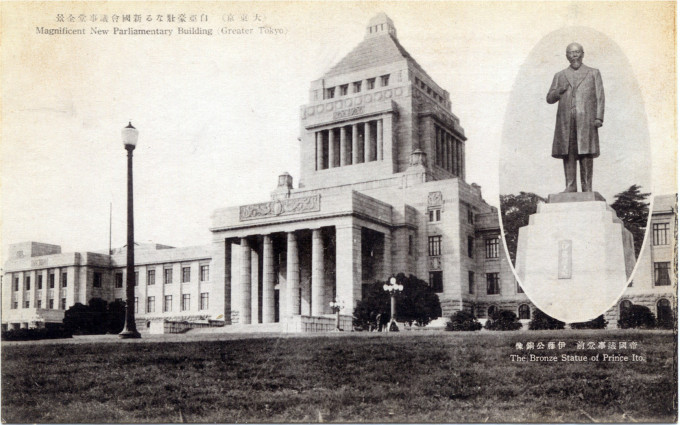

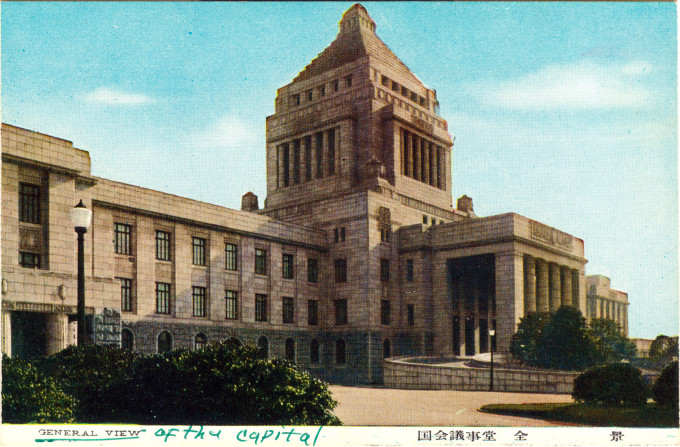

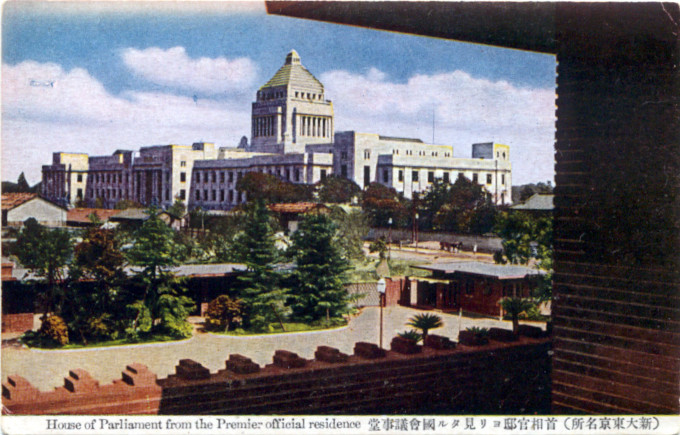

Exterior views, Imperial Diet Building, c. 1940

- Imperial Diet, c. 1936.

- Imperial Diet & Bronze statue of Prince Ito, c. 1936.

- Imperial Diet, exterior, c. 1940.

- Elevated view of the Imperial Diet, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, as seen from the Prime Minister’s residence, c. 1940.

- The National (formerly Imperial) Diet, c. 1950.

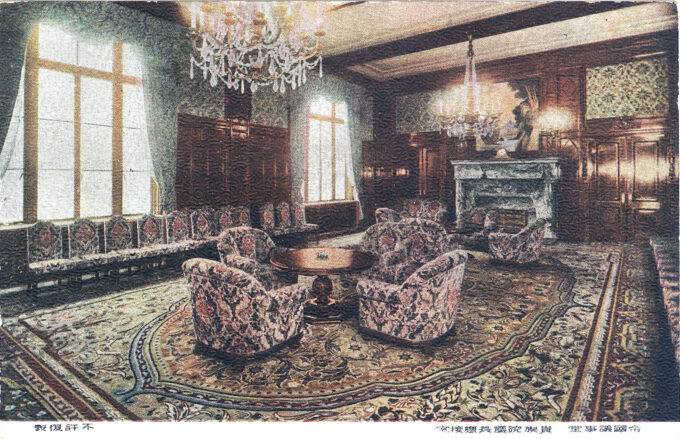

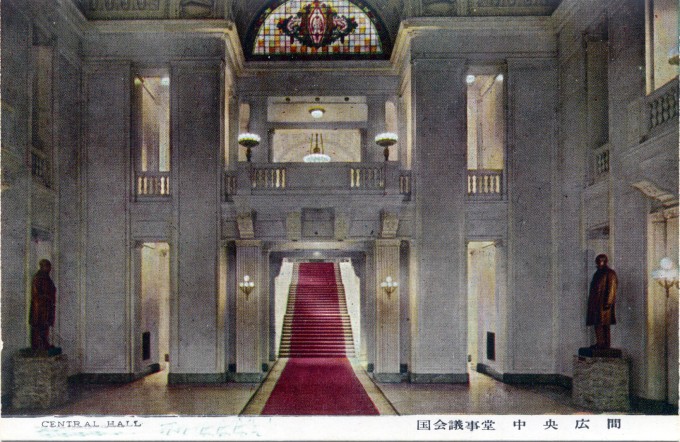

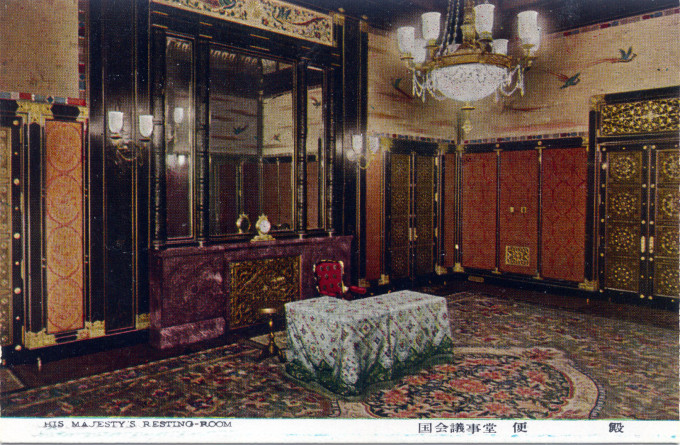

Interior views, Imperial Diet Buildiing, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, central porch, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, central hall, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, His Majesty’s resting room, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, House of Representatives, c. 1940.

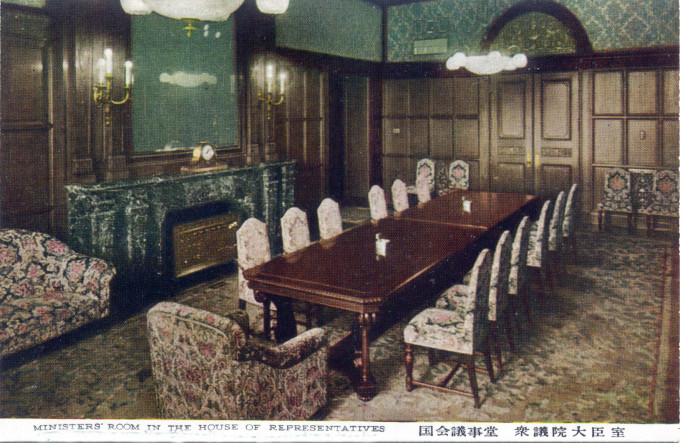

- Imperial Diet, Minister’s room, c. 1940.

- Imperial Diet, member’s dining room, c. 1940.

Pingback: Tokyo City Hall, c. 1910-1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Exposition celebrating the 70th anniversary of the “Meiji Assembly”, Ueno Park, Tokyo, 1938. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo