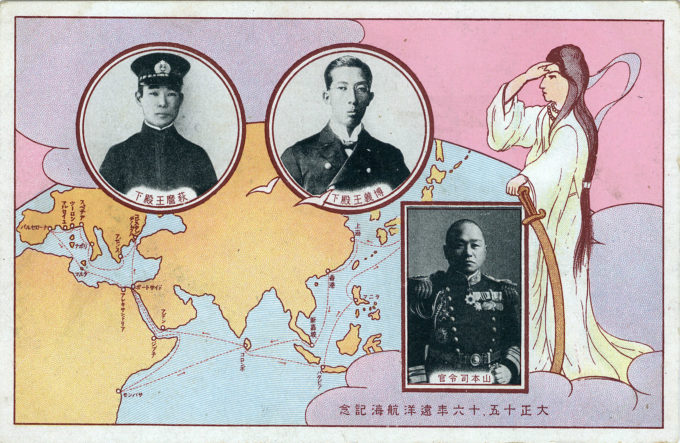

I.J.N. training cruise to the Mediterranean Sea, 1926-1927. The armored cruisers Azuma and Izumo departed the Naval Academy at Yokosuka on June 30, 1926 with a crew of cadets of the 54th academy class for the Mediterranean Sea with goodwill port calls in Shanghai, China; Hong Kong; Colombo, Ceylon; Port Said, Egypt; Constantinople, Turkey; Athens, Greece; Naples, Italy; La Spézia, Italy; Toulon, France; Marseilles, France; Barcelona, Spain; Malta; Alexandria, Egypt; Djibouti; Mombaza, Kenya; Batavia, Dutch East Indies; and Manila, Philippines before returning to Yokosuka on January 17, 1927. The training fleet was commanded by Vice-Admiral Yamamoto Eisuke (pictured at lower-left, no relation to Marshal Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku). Also pictured are Prince Hagimaro (left), a cadet of the 54th class, and Prince Fushimi (right), a graduate of the 45th class (1920) who was serving on board the Izumo as the chief torpedo officer. The training voyage coincided with the death of Emperor Taisho on December 25, 1926.

See also:

Imperial Japanese Navy training cruise to Hawaii, the U.S. and Canada, 1914.

The Tokyo Nautical School training ship “Taisei Maru”, 1906.

“While the [training voyages] had the primary purpose of providing long-spell sea experience to cadets, they were also part of the grand adventure Japan had embarked on to interact with and learn from the West.

“The visits to port cities were official, and well-advertised; relatively large numbers of men were involved; the officers were generally articulate and good speakers of English; and there was growing interest in (and eventually disquiet about) Japan. All of this meant that training ships visits were big events and attracted a lot of popular and media attention.

“The earliest visits were in the 1870s and 1880s, when the ‘artistic, quaint Japan’ had entered the Western consciousness, but the ‘assertive, modernising Japan’ was yet one or two decades away. In Japan itself, questions about its place in the world, and consequent self-image, were only beginning to be seriously considered. This is reflected in the cultural representation aspects of the early navy visits, in the sense that there appear to have been few formal attempts at representation of nation as such.

“The navy men did, however, present entertainment. There were very popular public fireworks displays and open-ship days. There were also the invitation-only At Homes, where the officers entertained hundreds of local prominent citizens on the ships. This all fitted in nicely to the spectrum of Western, particularly British, formal entertainment; and herein is one key to examining the reception of the navy men: their audience perceived their behaviour as representation of a culture with many features identifiable in terms of the ideals of the Anglo-Saxon world.

“… The ‘spectacle’ aspect of training ships visits continued post-World War I [but] the step-up in friction between Japan and the white Pacific from the

Versailles Conference onwards was also keeping Japan in the news. This latter, along with the end of the [Anglo-Japanese] Alliance, brought even more self-conscious Japanese awareness of the need to harness the ‘spectacle’ to serve their public relations ends.“Vice-Admiral Kobayashi was quite open in 1928 when he told his audience at an Auckland Rotary dinner that an important aim of the training cruises was ‘to meet influential people, speak with them, eliminate misunderstandings, if there are any, and to cement the good relation between our two countries’ (New Zealand Herald 3 Aug. 1928).”

– Floating Theme Parks: The Cultural Relations Role of Japanese Imperial Navy Training Ship Voyages in an Anglo-Saxon World, by Ken McNeil, 2010

Vice-Admiral Yamamoto Eisuke graduated from the 24th Naval Academy (1899) and the 5th Naval War College. He was ranked 8th out of 18 students when he entered the Naval Academy, and ranked second out of 17 students upon graduation. Yamamoto participated in the Russo-Japanese War as a staff officer of the 2nd Fleet, and fought in the Battle of the Sea of Japan and other battles. In 1909, when he was a staff officer in the military command, he submitted a written opinion to his superior Yamaya , the commander of the second division in the military command, advocating the research and adoption of “flying devices”. Yamamoto would lead the Japanese Navy to develop air power, becoming the first person of rank in the I.J.N. to pay attention to its potential.

Yamamoto served as military attaché in Germany, was the principal of the Naval War College and, later, commander of the training fleet, before becoming the first chief of the newly established Naval Aviation Headquarters in 1927. After that, he held important positions such as Commander-in-Chief of the Yokosuka Naval Base and Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet (1929-1931).

Prince Fushimi graduated from the 45th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1920, ranked first in a class of 89 cadets. Prince Fushimi served his midshipman tour on the cruiser Iwate, and as a sub-lieutenant on the battleships Fusō and Kawachi. After completing coursework in naval artillery and torpedo warfare, he served as a crewman on Kongō, Hyūga, Kirishima and Hiei. After completing advanced training in torpedo warfare, he was assigned as Chief Torpedo officer on the destroyers Shimakaze, Numakaze, and cruisers Izumo and Naka. On 10 December 1928, he received his first command, the destroyer Kaba. He was subsequently captain of the destroyers Yomogi, Kamikaze, and Amagiri.

Prince Hagimaro graduated from the Naval Academy in March 1926. On April 20 of the same year, he was appointed as a member of the Imperial Family in the House of Peers. On January 20, 1928, he completed his aeronautics training by flying a Type 13 trainer aircraft. In July 1928, he joined the battleship Haruna, and after that served at the Yokosuka Naval Base and at the Naval War College (military history research), he was promoted to lieutenant in the Navy in November 1929. However, due to poor health, he was forced to retire from the navy in March 1932. On August 26, 1932, Prince Hagimaro died of acute peritonitis at Hase Bettei (Kamakura City). He was 26 years old. In 1936, his book Jutland Naval History Theory was posthumously published, a subject he had devoted his academic life to beginning after completing the 1926-1927 training cruise.