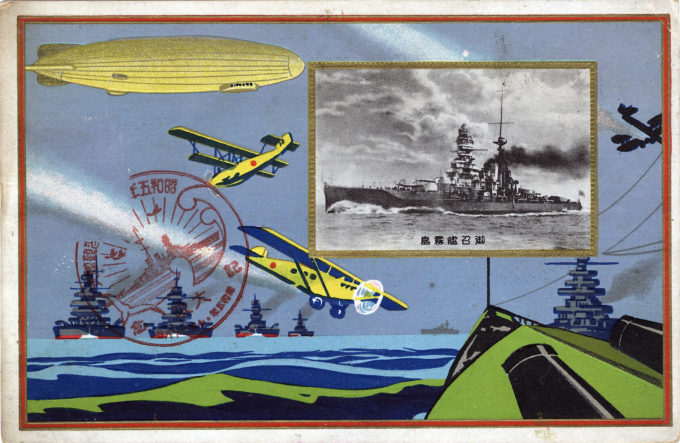

Grand Fleet Review, Osaka, October 1930. Pictured is the Emperor’s designated flagship, the battleship Kirishima, from which he conducted his review of the assembled Imperial Japanese Navy in the waters of the Inland Sea between Kobe and Osaka. The 1930 fleet review would be the first with participation by the newly-created Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service. Illustrations above include the air service’s Type 3 rigid airship, used for reconnaissance. Its design was based on the Italian Nobile N-3 design and was built under license in Japan.

See also:

I.J.N. Nobile N-3 semi-rigid airship, c. 1927.

Final Imperial Japanese Navy Fleet Review, 1940.

Emperor Meiji at the Grand Fleet Review, 1905.

Naval Battles of Miyako Bay and Hakodate (May 1869), Boshin War commemorative postcards, c. 1930.

Japan’s first naval review took place off-shore from Osaka the first year of Meiji Era, 1868.

The six warships that participated, Emperor Meiji’s ‘fleet’, were the property of the feudal lords of six pro-Imperial clans (Saga, Chōshū, Satsuma, Kurume, Kumamoto and Hiroshima). The review was directed by the Prince Minister of the Navy, with the Emperor reviewing the fleet from a stand erected on the coast of Osaka.

The entire fleet [in 1868], only a couple of which were considered ‘modern’ even by 1868 standards, displaced little more than the tonnage of a modern-day first-class torpedo destroyer, one of the smallest present-day battle vessels. The few ships-of-the-line considered ‘modern’ by 1868 standards, including the paddle-wheel steamer Kasuga, had been built in foreign shipyards and purchased by individual clans.

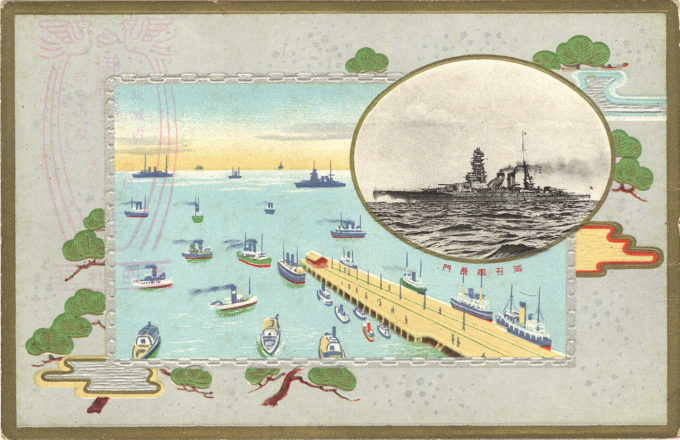

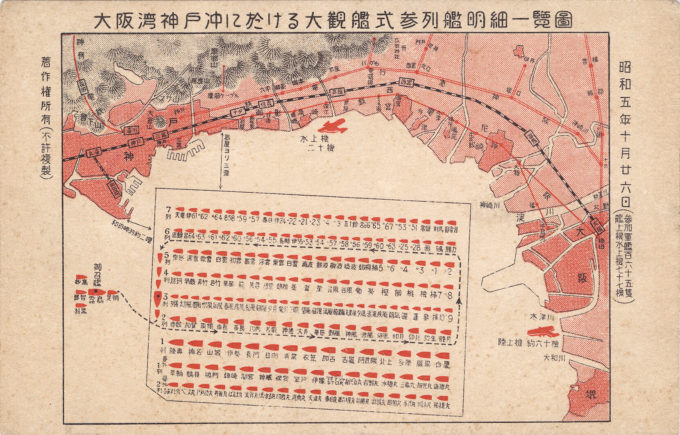

In sharp contrast, one-hundred sixty-four modern ships, the great majority launched from Japanese shipyards, along with 72 aircraft and one airship, participated in the 1930 Naval Review held on October 26 in the waters between Osaka and Kobe.

Grand Fleet Review, Osaka, 1930, showing the relative positioning of the Grand Fleet between Kobe and Osaka and the path took for the emperor’s fleet inspection from on board his designated flagship, the battleship Kirishima.

By 1920, the Japanese Imperial Navy was the third largest navy in the world, behind those of the British Royal Navy and the United States Navy, and was supported by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service for naval aircraft and airstrike operation from the fleet. Fixed-winged aircraft were augmented by the commissioning of rigid and non-rigid airships, including an airship, the Type 3, built under license by Fujikura-Mitsubishi based on the Nobile N-3 from Italy (illustrated in the postcard at the top of the page).

In 1921, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched Hōshō, the first purpose-designed aircraft carrier in the world. It would go one to develop a fleet of aircraft carriers second to none. At the 1930 Grand Fleet Review, the Hōshō was joined by two more recently-commissioned carriers, Akagi and Kaga.

Grand Fleet Review, 1930. The general public was able to view the Grand Fleet from the vantage of ferry boats that circled through the assembly. Inset photo: Nagato-class battleship.

“In general, the strategic outlook of the Imperial Japanese Navy was from its beginning decisively shaped by limits on its armaments.

“The navy went to war against the Peiyang Fleet of the Ch’ing Dynasty in 1894-95 with well-gunned but lightly armored ships, being unable to afford the heavy vessels that German yards provided to the Chinese. It opposed the Russians in 1904-05 with the best battleships Britain could supply but, because of Japanese financial and industrial weakness, fewer than the Russians had. The naval arms limitations treaties of the interwar era created a situation for Japanese naval planners that was different from the past only in that limitations came from the outside, in the form of international agreements.

“The Washington Treaty put a ceiling on the size and number of capital ships starting in the early 1920s, and the London Treaty further curtailed strength in other types of ships from 1930 onward. The result was that, even in the period of naval rearmament during the 1930s, Japanese naval strategy continued to reflect a strong conviction of material inferiority. While becoming one of the most powerful navies on earth, the Japanese navy still thought of itself as an underdog.

“… The navy might be consigned to a permanent position of inferiority under the [treaties], but its leaders felt that it might well exceed the United States in the seriousness of its commitment to its task. Even before this period the navy upheld the tradition of the seven-day workweek – one navy slogan was ‘getsu, getsu, ka, sui, moku, kin, kin,’ meaning that the navy week was ‘Monday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Friday’.

“Around 1927 high priority was assigned to night fighting as the principal means of attrition operations to precede the decisive battle. In the organization of the Combined Fleet for 1929, the command and responsibility for night raids was assigned to a night battle force under the commander of a heavy cruiser squadron. This commander also became head of the advance guard forces.”

– Japanese Naval Preparations of World War II, by Rear Admiral Hirama Yoichi, JMSDF (Retired), Naval War College Review, Spring 1991

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. The Emperor [beneath the awning] on board his launch, to be transported to his personal flagship, the battlecruiser Hiei to review the Fleet.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. Kongo-class battlecruiser Hiei, the Emperor’s personal flagship.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. “The sight of all the ships in the harbor at night, turning it into a fortress.”

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. The Emperor’s flagship, Hiei (left), passing the assembled fleet in review.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. On board Hiei, reviewing the destroyer squadrons of the fleet.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. On board Hiei, reviewing the fleet.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. The naval aviation units fly-by the destroyer and submarine squadrons at the viewing ceremony.

- Grand Fleet Review, Osaka-Kobe, 1930. The emperor’s flagship, Hiei, completing its review of the assembled fleet.

Pingback: Kobe Port Opening Exhibition and Naval Review, Kobe, 1930. | Old Tokyo