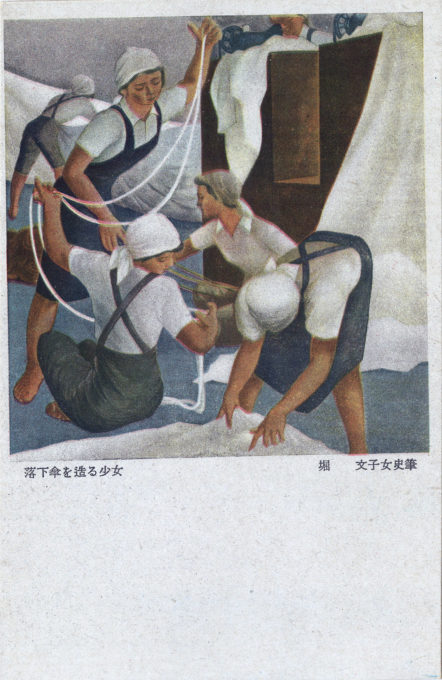

“Girls manufacturing parachutes”, propaganda postcard, c. 1945. Silk manufacturing in Japan had expanded rapidly during the Meiji Era but, primarily because of the creation of man-made fabrics (principally rayon), experienced an equally dramatic decline in the Taisho and early Showa periods. Then, a US embargo in 1940, imposed because of Japan’s 1937 invasion of China, effectively eliminated Japan’s overseas market for silk. With the onset of the Pacific War, when the large-scale production of parachutes for the Imperial army and navy spurred a rapid increased demand for silk, wartime labor shortages soon brought millions more women into the Japanese work force than in any prior period since the Meiji Restoraton.

See also:

Imperial marine paratroopers at the Battle of Manado (Menado), propaganda postcard, c. 1940.

“Grab the weapon for production increase”, propaganda postcard, c. 1940.

“A few months before the Pearl Harbor attack, the Japanese military added a novel type of airborne infantry to its war machine. Japan’s new paratroop units, set up secretly and quickly sent into action, were to have a long-lasting impact on the country’s home front and industry.

“… Within days after their initial deployments [in 1942], Japan’s paratroopers saw their role change radically. Secret shadow warriors turned into media stars that were thrust into the limelight … While the media engaged in such idealistic glorification of the airborne soldier and his silk parachute, Japan’s silk industry was bound to reap great material benefits from the paratroopers’ exploits.

“… One manufacturer reaped the greatest profits from the parachute boom. Fujikura, founded in 1901, initially engaged in the production of rubber and electric wire. In June 1913, the company began experimenting with silk and cotton fabric for balloons, airships, and aircraft. Fujikura also engaged in the research and design of parachutes and presented its first rescue parachute for balloon and airship crews in 1919 … In October 1939 Fujikura set up its new branch, Fujikura Aviation Industry, that successfully established a monopoly on parachute production in Japan.

“… In many ways the paratroopers’ saga is closely interwoven with that of the workers at Fujikura’s factories. Both would come to share a common narrative of devoted volunteers, determined warriors, and, ultimately, patriotic self-sacrifice.

“Before Fujikura could establish itself as a major segment of Japan’s wartime industry a serious problem had to be solved. The company’s dramatic production increase required an equally massive workforce expansion—a major challenge at a time when military conscription caused a severe labor shortage.

“To compensate for the lack of male factory workers, Fujikura began to recruit girls and women as volunteer workers from all over Japan. Mass recruiting was successful, and soon these female volunteers made up about a half of the factory workers. After silk reeling and weaving, parachute production also developed into a highly gendered workplace.

“Fujikura’s management aimed to further improve production capacity by boosting workers’ morale. The book that the company published in 1943, Rakkasan o tsukuru kokoro (The Spirit of Making Parachutes), celebrated the importance of the Fujikura workers and their products.

“The book featured several contributions from Fujikura’s employees … They suggest an attitude that goes beyond the purely material aspects of parachute production. One worker declared that ‘before the paratroopers carry out their crucial missions, they put their parachutes on an altar and pray for victory. Likewise, with every stitch, we Fujikura workers instill our wishes for victory into each parachute.’

“A factory girl from Fujikura’s Honjo [Tokyo] plant contributed a poem that draws a telling parallel between the young factory girls and the soldiers on the battle front:

We young maidens brace up our frail bodies for the country.

Today we will stitch the white silk again.

While we make parachutes our mind is pure,

strong, and calm just like the white silk.

When we are stitching with our sewing machines our mind

is just like that of a soldier carrying his gun to the battlefield.

– “Heavenly Soldiers and Industrial Warriors: Paratroopers and Japan’s Wartime Silk Industry”, by Jürgen Paul Melzer, The Asia-Pacific Journal, September 2020

Pingback: “Assembling a comfort bag” propaganda and advertising postcard, c.1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “Student at Tokyo Army Aviation School” propaganda postcard, c. 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo