“Japan’s first fire service was founded in 1629 during the Edo period, and was called hikeshi (lit. ‘fire extinguish’).

“During the Meiji Period, the hikeshi was merged into the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department in 1881. During this period, pumps were imported and domestically produced, and modern firefighting strategies were introduced.

“The fire service would remain part of the police department until Occupation era police reforms in 1947 separated it from the police to become an independent agency. The present-day TFD is the largest urban fire department in the world with a paid firefighter roll call of 18,408 and a volunteer firefighting corps of over 22,000 people.

“The Tokyo Fire Museum is at Yotsuya 3–10, Shinjuku-ku. It has a large collection of historic firefighting apparatuses. The museum has firefighting history of the 17th and 18th centuries with large, scale-model dioramas showing scenes of destruction from past events. Models shows the uniforms and equipment that was used during that time.”

– Wikipedia

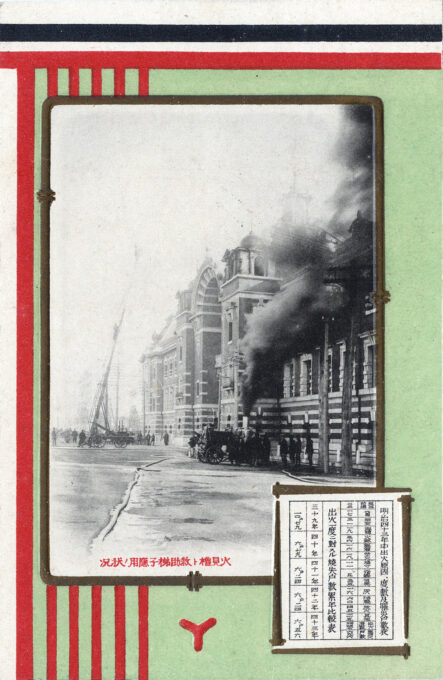

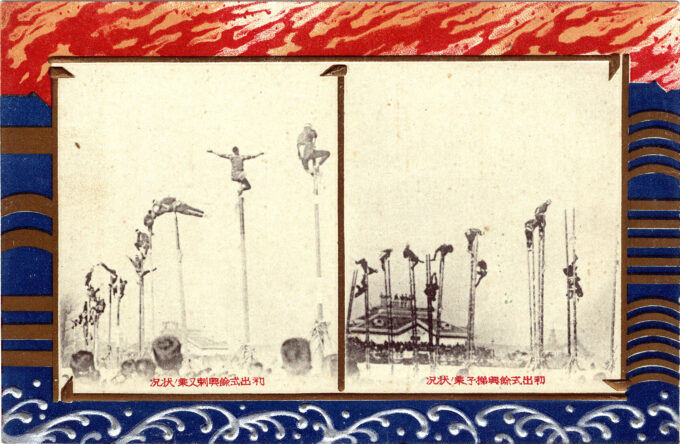

Fire Brigade Parade, New Year’s Day, Tokyo, 1912. The annual tradition of dezome-shiki is still performed by stunt firefighters to welcome in each new year.

See also:

Dezome-shiki (“First event”), New Year’s Day, c. 1910 & 1960.

2600th Founding Anniversary Nissan pumper fire truck, c. 1940.

“Firemen of the Edo period held a dual reputation among the Japanese citizenry. On one hand, firemen were admired for their bravery. On the other hand, they were loathed because of their lower class origins; nothing more than rowdies, criminals and drunks.

“Fire fighting jobs provided these unsavory characters with an income and a heroic reputation that would not ordinarily be available to them. Overall, ordinary citizens lionized the hikeshi-firemen as honorable bandits and brave troublemakers.

Fire Brigade Parade, New Year’s Day, Tokyo, 1912. What might first appear to be a fire out of control (all that black smoke!) is, in reality, a coal-fueled steam-powered pumper being demonstrated during the day’s festivities.

“Body tattoos, widely popular among the men of the Edo fire brigades, displayed courageous and fearsome symbols, like dragons, and mythical battle heroes. Flamboyant tattoos demonstrated their masculinity and solidarity with one’s comrades. However, that changed when the Edo period ended and the Meiji Restoration began.

“… Among one of many changes, the new government regarded tattooing as a sign of barbarism, and in 1872, prohibited all body tattoos even for the respected firefighter.

“The new tattooing regulation did not set well with the spirited firefighters but nevertheless they understood that the law must be strictly obeyed. And, suddenly at the same time, thousands of tattoo artists were out of a job. What to do? Someone came up with the bright idea of having the former tattoo artist embellish the interior of the fireman’s jackets in the tsutsugaki dyeing method with the same heroic images that were once allowed as body tattoos.

“The tattoo artist created a permanent replacement occupation and the firefighter could continue displaying the same prideful heroic images that were once body tattoos. Thus, the genesis of the colorful and dramatic reversible Japanese fireman’s hikeshi-bantan [Wikipedia] fire jacket.”

– History of Japanese Hikeshi-bantan Fire Jacket, KimonoBoy.com