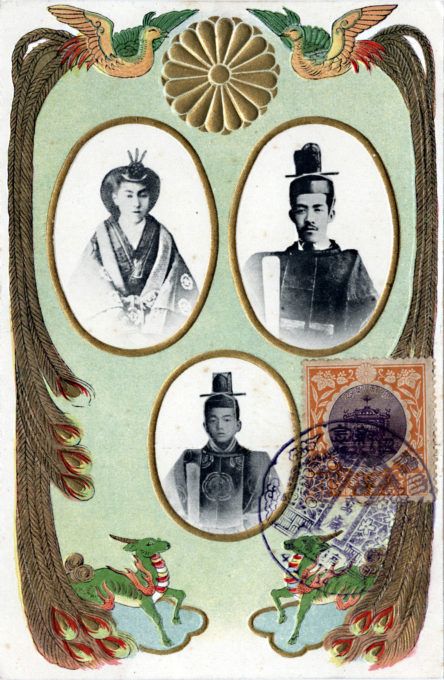

Commemorative postcard of Emperor Taisho’s enthronement, 1915. The emperor had ascended to the throne in 1912, upon the death of his father, Emperor Meiji. A young (14-year old) Prince Hirohito – the future Emperor Showa – is seen in the lower photo inset. Hirohito would ascend to the throne in 1926. His own enthronement rites would occur in 1928.

See also:

Celebrating the Enthronement of Emperor Showa, 1928.

“In 1883, the Imperial Rescript was announced to designate Kyoto as the site for the Emperor’s sokui-shiki (enthronement rites) and its related Daijosai (Great New Food Festival). Not everyone comprehended the clothing rules for these ceremonies – the types and how to wear them. Instructions were given by specialists called yusokukojitsu, who researched the old aristocratic records. ‘Clothing Training Sessions,’ or Emon koshu-kai, were arranged at the Imperial Household Agency and led by the Yamashita and Takakura families, who had been in charge of the emondo (techniques for dressing) until 1870.

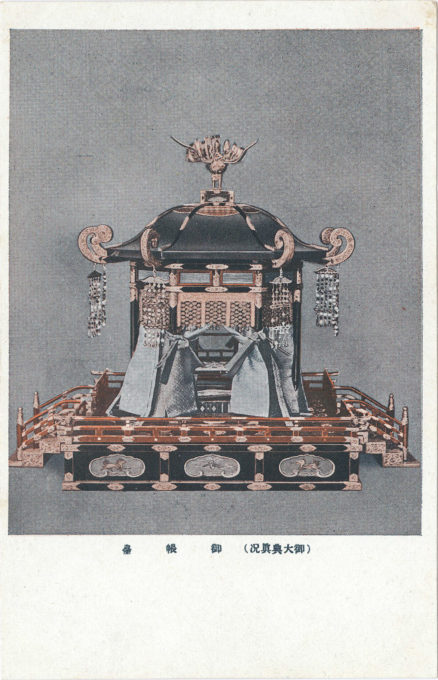

A 1915 postcard image of the special throne, Takamikura, used for the enthronement Emperor Taisho. First came a 3-hour ceremony in which the new emperor ritually informed his ancestors of his impending enthronement, followed by the enthronement itself which took place, per tradition, in an enclosure called the Takamikura, containing a great square pedestal upholding three octagonal pedestals topped by a simple chair. This was surrounded by an octagonal pavilion with curtains, surmounted by a great golden Phoenix.

“The result can be seen in the November 1915 Taisho tairei, Emperor Taisho’s enthronement rites. For this event, he departed Miyagi in a state carriage, transferred at Tokyo Station to the Tokaido Main Line to Kyoto Station, from there rode a carriage to the Palace.

“In the morning of the enthronement (November 10), he worshipped at the Palace Sanctuary (Kensho), reporting his impending succession to his imperial ancestors. For the ceremony, he wore a white imperial robe of the sokutai type, then changed to a dyed-yellow imperial robe (korozen no goho) also of the sokutai type in the afternoon for his enthronement at Shishin Hall, Kyoto Imperial Palace.

“… Among the attendants were some dressed in attire from former eras. Prime Minister Okuma Shigenobu wore an ikan-sokutai and his wife an uchiki-bakama (a simplified version of the twelve-layer robe). The attendants in the Emperor’s carriage procession wore Western grand ceremonial garb and formal uniforms of the army and navy.

“… Such important traditional practices and attire related to imperial succession did not substantially change at the subsequent Showa and Heisei enthronements.”

– Fashion, Identity, and Power in Modern Asia, edited by Kyunghee Pyun & Aida Yuen Wong, 2018