See also:

Kinkiro Hotel, Enoshima, c. 1910

Katase Beach, Enoshima, 1910-1960.

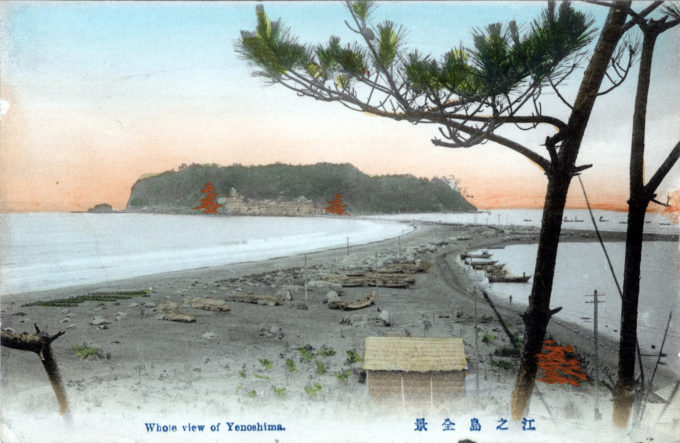

“Whole View of Yenoshima” from Katase, c. 1910.

“I, of course, have been to Enoshima, like other people — lovely Enoshima, an island at high tide, a peninsula at other times, beautiful under all circumstances and at all seasons of the year; not less attractive, perhaps, in winter, when the great Pacific rollers on the beach are shadowed with deep violet, more threatening to look on than those fairy walls of emerald and pearl that rose and fell under the summer sun.

“You may be taken to Enoshima by a guide in a train, if you like, and if you are a tourist that is what you are almost sure to do. But the true plan is to go by yourself on a bicycle and lose your way. Then you will see charming visions innumerable that never show themselves from the train, and you learn incidentally how gross a fallacy is that which asserts the necessity of a road for a bicycle to travel on.

“For you prove experimentally that a track a few inches wide — its width regulated by a time-honoured prescription, though not so, perhaps, its innumerable hills and holes — will answer the same purpose excellently well, and, over and above the picturesque and antiquarian interest of the trip, you have the chance of falling into the very dubious black water on either side, and the excitement of steering yourself over bridges of a single plank largely gone in the middle.

“Whether this be the best way or not, in any case it was the one I chose for my first pilgrimage to Enoshima.”

– Present Day Japan, Augusta M. Campbell Davidson, 1908

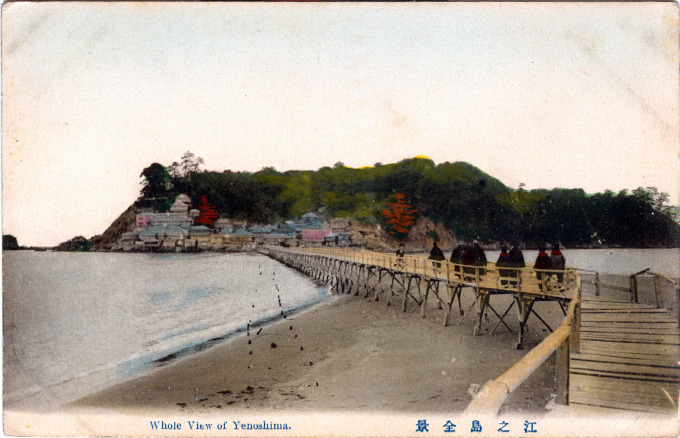

“Driving five miles down the beach, the island of Enoshima is reached. At low tide the jinrikisha can go to the foot of one of the steep streets, but at high tide a ferryboat plies across a stretch of water. There are beautiful walks through the temple groves crowning the island, and the cave temple to the Goddess Benten may be visited at low tide. Its tea houses serve fish dinners and each one commands some specially fine view.”

– East to the West: A Guide to the Principal Cities of the Straits Settlements, Japan and China, by Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, 1898

“Enoshima presents a high wooded aspect, and through the foliage on the heights one can obtain glimpses of many tea-houses. From the earliest ages the island was sacred to Benten, the Buddhist goddess of love.

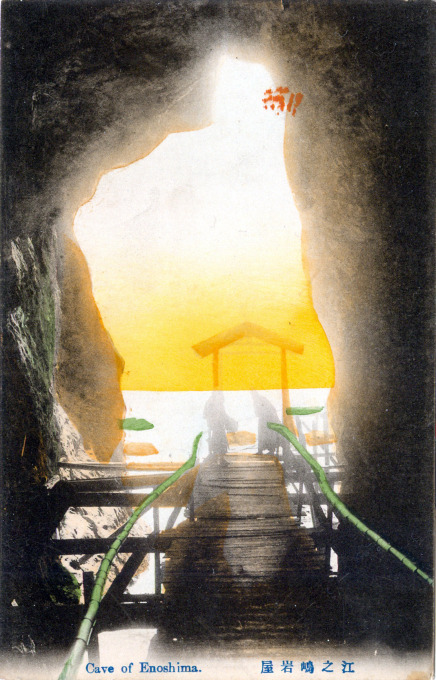

“Nearly all of the temples are dedicated to Shinto goddesses. The most sacred spot is a cave on the far side of the island, one hundred and twenty-four yards in depth, the height at the entrance being at least thirty feet.”

– Travels in the Far East, by Ellen Mary (Hayes) Peck, 1909

Part playground, part reverential retreat, Enoshima was said to have arisen out of the sea in the 6th-century CE. It is home to two religious icons: Benzaiten, the deity of music and entertainment; and a shrine marking the entrance to the anatomically-shaped Iwaya cave.

Enoshima’s heritage was rooted in Buddhism and Shinto and, until 1870, numerous shrines and small temples dotted the island. The area later developed into a romantic resort (served by the Odakyu Line’s “Romance Car” express) and, with post-war prosperity, the area surrounding Enoshima became a very popular “a day at the ocean” destination for urban dwellers.

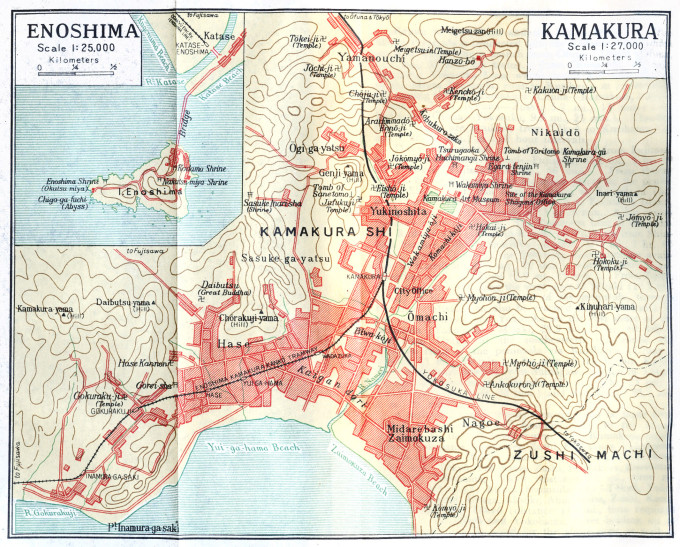

Fujisawa, on the mainland, is now a resort town with easy access to Tokyo and Yokohama. Amenities there include Katase Beach and the scenic Enoshima Line (Enoden) running between Kamakura and Fujisawa along Sagami Bay.

“Enoshima, being a popular holiday resort, is full of excellent inns. The best are the Iwamoto-in and Ebisu-ya in the village, and the Kinkiro higher up. There is fair sea-bathing. The shops of Enoshima are full of shells, corals, and marine curiosities generally, many of which are brought from other parts of the coast for sale.

“The beautiful glass rope sponge, called hosugai by the Japanese, is said to be gathered from a reef deep below the surface of the sea not far from the island of Oshima, shoe smoking top is visible from the south on a clear day.”

– A Handbook for Travellers in Japan: Including the Whole Empire from Yezo to Formosa, Basil Hall Chamberlain & W. B. Mason, 1900

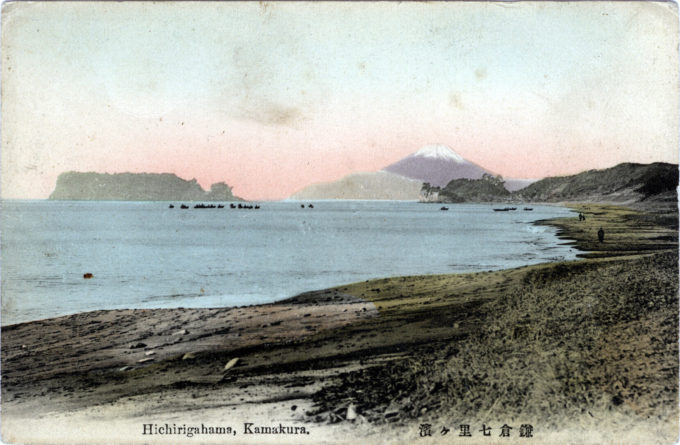

- Untitled, c. 1910. Long view of Enoshima, at high tide, overlooking Hichirigahama.

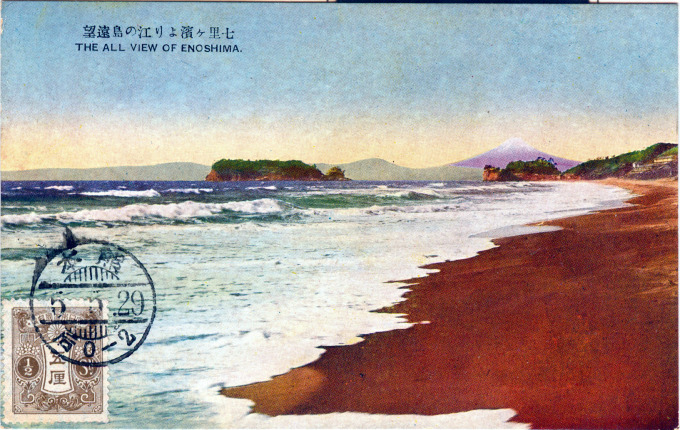

- “The all view [sic] of Enoshima”, c. 1910, looking down the length of Hichirigahama. Mt. Fuji can be seen in the distance.

- “Natural Beauties at Enoshima”, Enoshima, c. 1950, from Katase Beach.

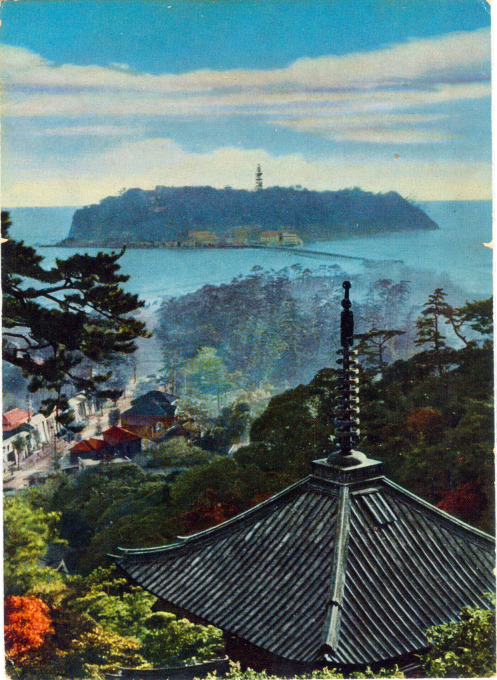

- Scenic view of Enoshima, c. 1950.

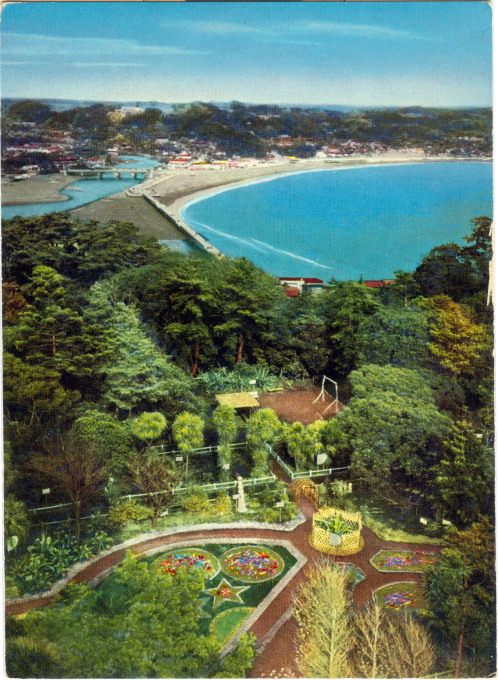

- Aerial view of Cocking Botanical Garden, looking toward Fujisawa, c. 1960, from atop Heiwa Tower.

- Untitled, c. 1960. View of Enoshima from Fujisawa. Heiwa Tower stands above the island.

A 19th-century British merchant, Samuel Cocking, bought much of the island uplands in 1880 for the building of an electricity-generating plant while co-developing an extensive botanical garden (which still exists). The botanical greenhouse was destroyed in the 1923 earthquake and never replaced. The Heiwa Tower, erected in 1951, stood for many years atop the island’s peak, used as both lighthouse and public observation deck. (It was replaced in 2003 by Enoshima Sea Candle.)

“Straight before us lay the picturesque island in the waning light, an irregular outline of rock, crowned with a forest of trees from amid which glimmering lights shone out. To the right stretched an arm of the sea rolling up its wavelets on the long low sandbar.

“From the sea rose up the dim faint outline of Fujiyama, purple in the gloaming, and around above her were piled up rich clouds of crimson and gold, behind which the sun had just sunk leaving but a train of his splendor behind.”

– Clara’s Diary: An American Girl in Meiji Japan, by Clara A.N. Whitney, edited by M. William Steele & Tamiko Ichimata, 1979

Pingback: Kinkiro Hotel, Enoshima, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Inamuragasaki, Enoshima, c. 1960. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Yuigahama Beach, Kamakura, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Hayama Beach, Kamakura, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Seven Lucky Gods of Japan, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: "Whole View of Yenoshima" from Katase, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Heiwa Lighthouse, Enoshima, c. 1960. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Enoshima Island at low tide, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo