See also:

Daibutsu at Kamakura, c. 1910

Hachiman Temple, Kamakura, c. 1910

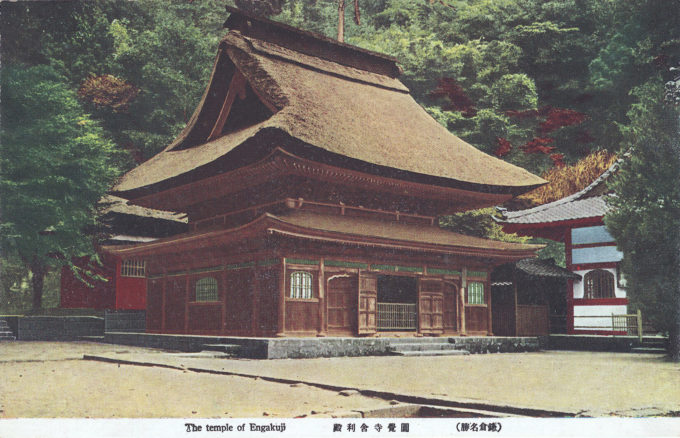

“I stood before the great gate at Engakuji. The naked guardians grimaced, the carved eaves stretched above me, the roof soared and touched the pines. I was about to enter the abode of the Buddha, the world of Daruma, the land of Zen. I said the word softly to myself – the cicada-like drone of the syllable, the sudden halt of the consonant.

“As I did a soft summer breeze struck the overhead pines. The needles rustled and from them fell a fragrance I had known as a child. Looking up, deep into that glimmering green, I felt a memory surface, then turn and disappear before I could recognize it. But its passing brought a tear – just one, but real.

“Then I was walking through the gate and into the temple, only an hour from Tokyo but already another world to me … Around in back I found the small tiled-roofed house. There I waited, letter and gifts in hand, waited for my teacher. I had read that the Zen adept waited all day – all night, too, through rain, through snow. None of this, however, proved necessary, for the man I had come to see, who had not known I was coming or that he was my teacher, soon noticed the large foreigner standing in the cabbage patch and came out on the veranda.

“… Every Sunday I would appear with my crackers and cheese, canned meats, peanut clusters – offerings from the PX for my sensei. These he would graciously receive and carry off to the larder. In return I would be given my cup of tea and a talk. It was always about Zen and I never understood a word. Or, rather, it was the words alone I understood – and sometimes the sentences, but never the paragraphs. Still, I was learning.

“Other discourses I had heard were rational, logical, but Dr. Suzuki’s were something else. The process seemed associative, one thought suggesting another, apparently at random. But, as one idea followed another, I saw the randomness was only apparent. Each was attached to the other by the linearity they formed.

“And as I listened I understood that there were other means of structuring thought, ways of thinking different from those I had always known and believed unique.

“This was really all I ever learned from my teacher but it was a lesson of the greatest importance. Dr. Suzuki never gave me satori in exchange for my Velveeta, but he gave me the priceless apprehension of other modes of thought.”

– The Japan Journals: 1947-2004, by Donald Richie, edited by Leza Lowitz, 2004