Emperor Meiji funeral hearse. Postcard dated 9 Dec 1912. By the end of the Meiji era, in 1912, Japan was still primarily an agrarian nation but had rapidly developed its industrial might and capacity during Mutsuhito’s 45-year reign. With its victory over Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), Japan joined the world’s Great Powers.

See also:

Dedication of Meiji Shrine, Tokyo, 1920.

Count (General) Nogi Maresuke

“On the night of 13 September 1912, the funeral procession for Emperor Meiji left the palace grounds.

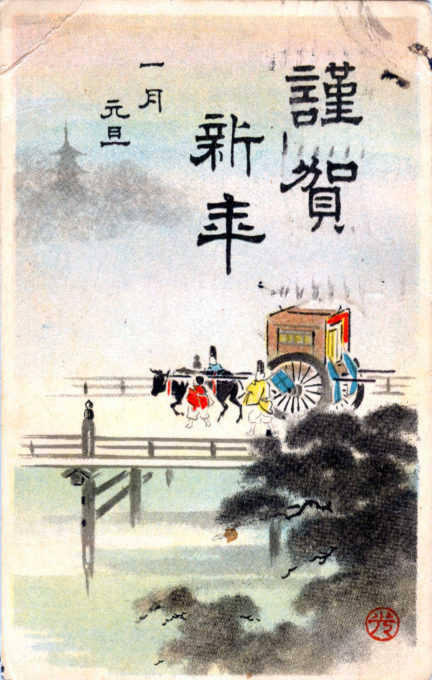

Emperor Meiji’s ox-drawn funeral hearse New Year’s postcard, 1913 (coincidentally the Year of the Ox).

“Born in 1852, the year before the Perry Expedition’s first visit, the emperor had ascended the throne in 1867 and presided over an era of unprecedented change.

“As his funeral cortege made its way through the streets of Tokyo, the black lacquer wheels of his ox-drawn cart reflected both the glow of torches and the glare of arc lights. Crowds of mourners lined the three-mile route and watch silently as thousands of courtiers, officials, military guards, and Shinto priests accompanied the imperial casket. Cannons thundered and temple bells tolled in salute.

“To a character in Natsume Soseki’s 1914 movel Kokoro, the booming of the cannon ‘sounded like the last lament for the passing of an age.’ Soseki, modern Japan’s most beloved writer, had felt Japan shift under his feet.”

– Outposts of Civilization: Race, Religion, and the Formative Years of American-Japanese Relations, by Joseph M. Henning, 2000

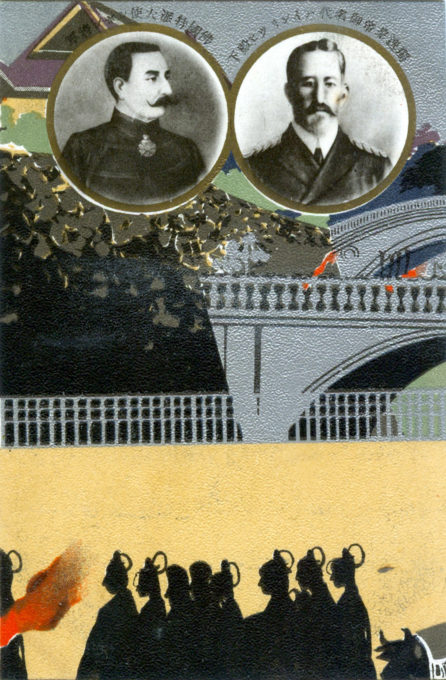

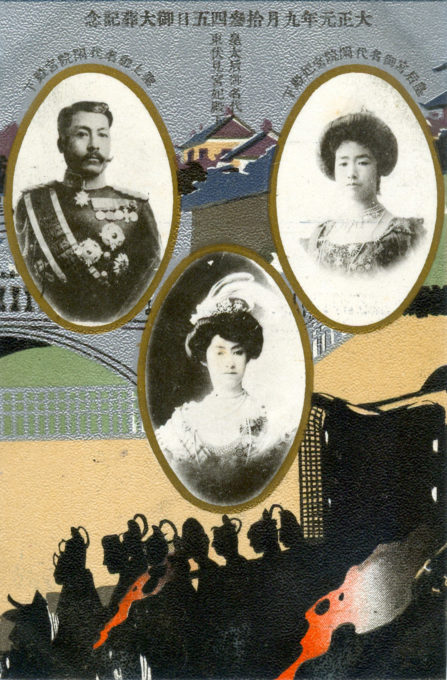

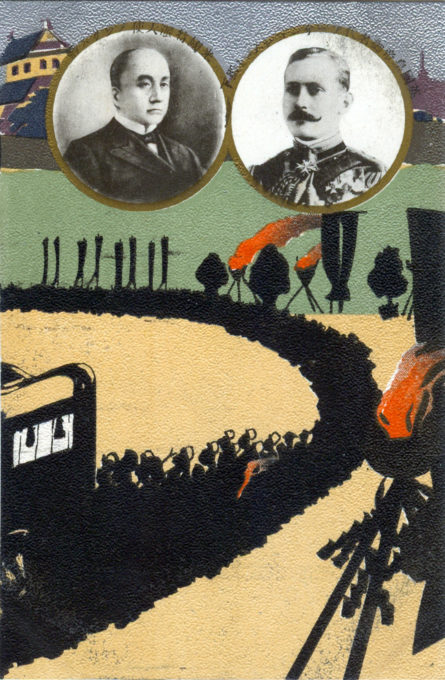

The Emperor Meiji funeral cortege, departing the Imperial Palace, and official government representatives in attendance

- Left: King Albert I, of Belgium. Right: King George V, of Great Britain.

- Top: Prince Kan-in Kotohito and Princess Chieko. Bottom: Empress dowager Shōken, widow of Emperor Meiji.

- Left: Secretary of State (U.S.) Philander C. Knox. Right: Kaiser Wilhelm II, of Germany.

“The tone of voice of the newsboy selling extras was not the animated tone one hears during war time; nor was it the flippant tone characteristic of some trivial event being deliberately overplayed, or the intrigued tone of a political reform. Rather, it was a sad, despondent voice that one heard as the newsboy ran down the street.

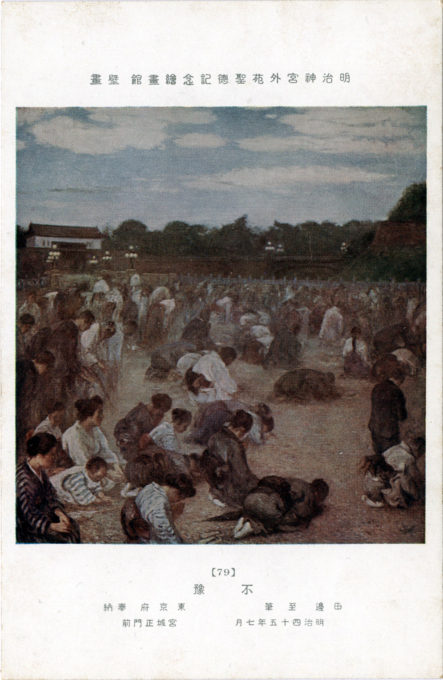

No. 79: Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery, c. 1960. “The Emperor’s Final Illness (July 1912).” People gather outside the Tokyo Imperial Palace to pray for his recovery.

“‘His Majesty’s condition is critical’ … ‘His Majesty’s state of health as of yesterday’ … and then, over the next four or five days, it was reported that crowds had gathered near Nijubashi to pray constantly for His Majesty’s recovery.

“The whole nation was stricken with grief. Everyone spoke in hushed tones, with a look of sorrow on their face.

“It was impossible to stop nature’s forces entering the Palace grounds and into the very of the Palace itself to where the Emperor lay. The best doctors in the nation were powerless.

“Who could fail to be moved to tears by the thought of the illustrious life of His Majesty Emperor Meiji, ‘Mutsuhito the Great’, Lord of the Restoration, who despite being raised in adversity surmounted all manner of obstacles and perils to lead Japan to the state of wonderful international nationhood it enjoys today?

“There comes a time when one must bid farewell even to an emperor. It was no just me who felt this. The whole nation felt the same way.

“… I had been too young to pay my respects at such ceremonies as the accession and the change of capital [from Kyoto to Tokyo], but every time the Imperial Guard of Honour went in procession through the streets I was always to be found standing amongst the crowd at the roadside, paying my respects to His Majesty in an indirect way … I had never dreamt that the Imperial Funeral would take place so soon, without our even being able to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the accession.”

– “The Death of Emperor Meiji”, by Tayama Katai, Thirty Years in Tokyo, 1917 (translated by Kenneth G. Hensall, 1987)

(Clockwise, from upper-left) Emperor Taisho, late Emperor Meiji, widow Empress Shoken, Crown Prince Hirohito (future Emperor Showa), and Empress Teimei, c. 1915, commemorating the enthronement of the new emperor in 1915.

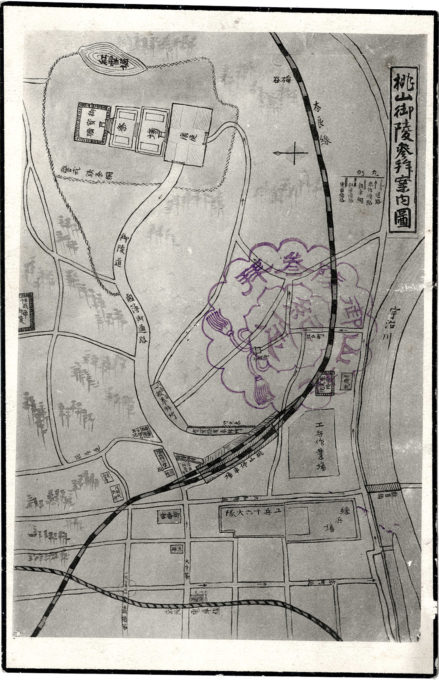

“Peach Hill [Momo-yama] was known anciently as Fushimi-yama, and for more than a thousand years it has reflected Kyoto’s greatness. Already heavy with the bones of long-dead Mikados, it was the scene, at 11 o’clock on the night of Sept. 14, 1912, of one of the most gorgeous and singularly impressive ceremonies ever witnessed in New Japan.

The Grounds of the Momoyama Imperial Mausoleum, Kyoto, c. 1915, built on the grounds of the former Fushimi-jo Castle.

“To the distant crashing and the reverberating roar of minute-guns; the wailing of bugles and the booming of gigantic temple bells; to the sound of the wild minstrelsy of priests and bonzes, the pattering of a weeping, drenching rain and the sighing of a vast concourse of mourning people – Japanese and foreigners alike – the mortal remains of Mutsuhito, the 123d Mikado, of the 68th generation from Jimmu Tenno, were laid tenderly in their last resting-place.

“Squads of soldiers and civilians, priests and laymen, foreign diplomats and servants of the Imperial Household – many holding sputtering pine torches on high to light the strange cortege – awaited the arrival from Tokyo of the funeral train — the first steam railway train ever to bear a Mikado to his grave! From the station a hundred picked men carried the wonderful catafalque [raised bier] to the sepulcher, into which the coffin was lowered over an inclined track.”

– “Terry’s Japanese Empire”, T. Philip Terry, 1914