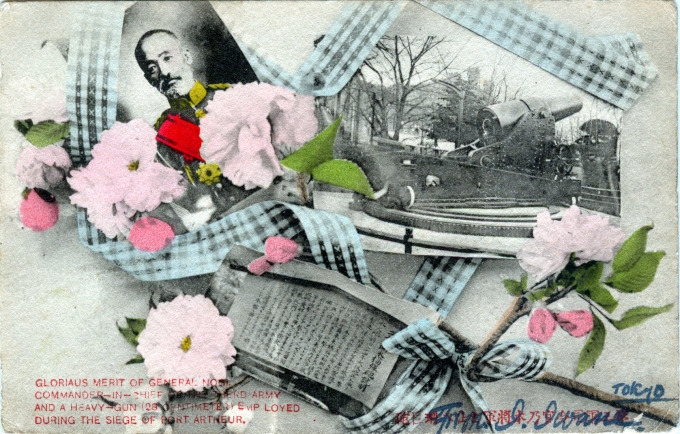

“Gloriaus [sic] merit of General Nogi, Commander-in-Chief of the Therd [sic] Army, and a heavy-gun (28 centimeter) employed during the Siege of Port Arthur.”

“Although it cannot be said that suicide is good, or that junshi is good, in the case of General Nogi it was truly a magnificent end. It was a glorious end to a bushi’s life that would have satisfied General Nogi.

“In fact, if one considers General Nogi’s usual thought, it was an event worth celebrating. However, if one considers losing a great man such as this, one must be deeply saddened. Our thought has two sides. In any case, the junshi suicide of General Nogi truly demonstrated the great strength of Bushido of our Japan. I believe it will certainly still produce great effects from now on.”

– Yamaga Soko sensei to Nogi taisho, essay by Inoue Tetsujiro, 1912 (excerpted from Inventing the Way of the Samurai: Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushido in Modern Japan, by Oleg Benesch, 2014)

Count Nogi Maresuke first distinguished himself as a military commander when he led the fledgling Imperial Army against the Satsuma Rebellion (1877) and again during the Sino-Japanese War (1895). During the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), however, his forces took heavy losses before taking Port Arthur in the final land battle of the conflict.

There were calls early in the campaign for Nogi’s removal as commander and Nogi wished to commit seppuku [ritual disembowelment] as atonement. Emperor Meiji himself stepped in with his support; that any tactical mistakes were due to Imperial orders. General Nogi was commanded by the Emperor to remain alive as long he, the Emperor, was alive.

After the war, General Nogi was elevated to peerage in 1906 and became revered as a national hero. He was also appointed head of the Peers’ School (1908-1912) where one of his pupils was the future emperor Showa. Count Nogi was also philanthropic, donating much of his personal fortune to hospitals for wounded soldiers and memorials for the fallen on both sides of the Russo-Japanese conflict.

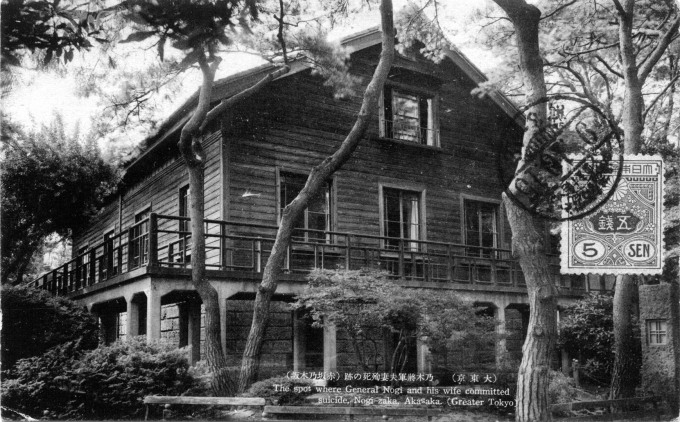

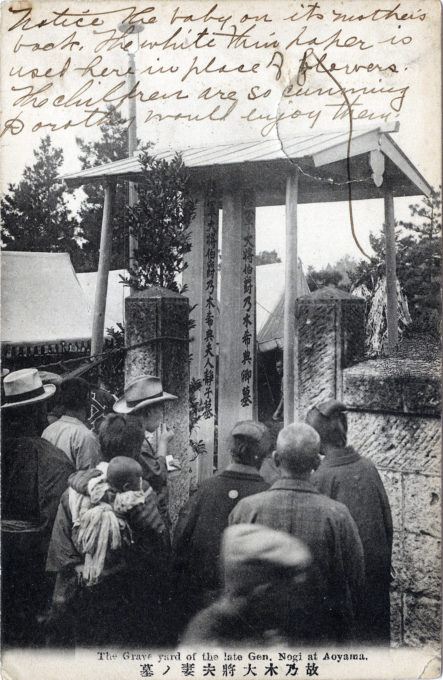

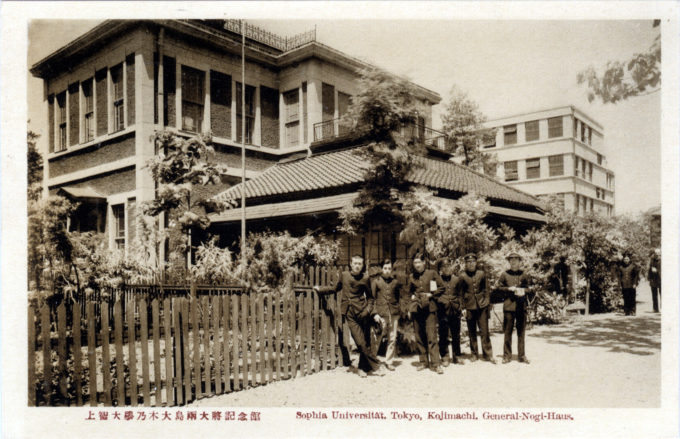

Upon the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912 both Count Nogi and his wife committed ritual suicide. (Following ones’ master into death was considered an act of extreme loyalty and sacrifice according to the Bushido code). State Shinto accorded Nogi kami [deity] status, and a shrine still stands on the grounds of his former residence in the Aoyama neighborhood of Nogizaka [Nogi hill] near Gaien Higashi-dori.

- The Nogi home at Nogi-zaka, Aoyama, c. 1920. Now a museum.

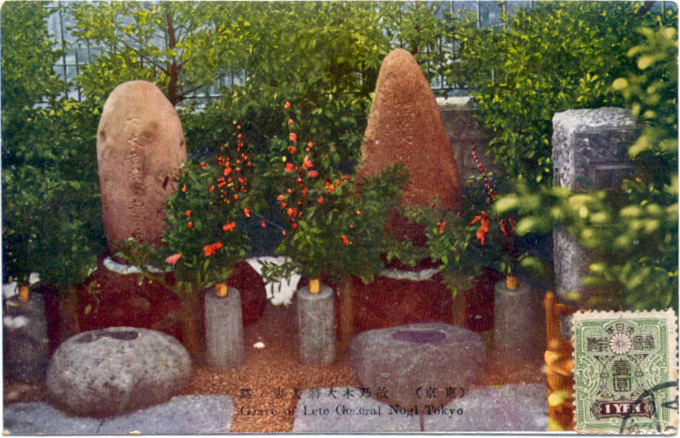

- Garden burial shrine of General and Mrs. Nogi.

“Nogi’s death poem, intended for public consumption, told the nation he was following his lord into death – a practice known as junshi that even the Tokugawa shogunate had considered barbaric and outlawed as ‘antiquated’ in 1663.

“Conservative intellectuals, given to decrying the collapse of traditional Japanese morality, interpreted Nogi’s suicide as a signal act of loyalty, pregnant with positive lessons for the nation, and its armed forces.

“Nantenbo, Nogi’s Zen master, was so enthralled with his pupil’s action he sent a three-word congratulatory telegram to the funeral: ‘Banzai, banzai, banzai.'”

– Hirohito And The Making Of Modern Japan, Herbert P. Bix, 2000

Pingback: Baron Komura, the plenipotentiary of peace negotiation, leaving Tokio, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Akasaka Mitsuke, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Sophia University, Yotsuya, Tokyo, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Emperor Meiji's funeral hearse, 1912. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: “Monument of [Hill] 203”, Port Arthur, Manchuria, c. 1910. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Exposition of Shining Technology (2,600th National Foundation Anniversary), 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Crown Prince Hirohito’s Tour of Europe, 1921. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “General Head-Quarters of the Manchurian Armies in Mukden”, 1906. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo