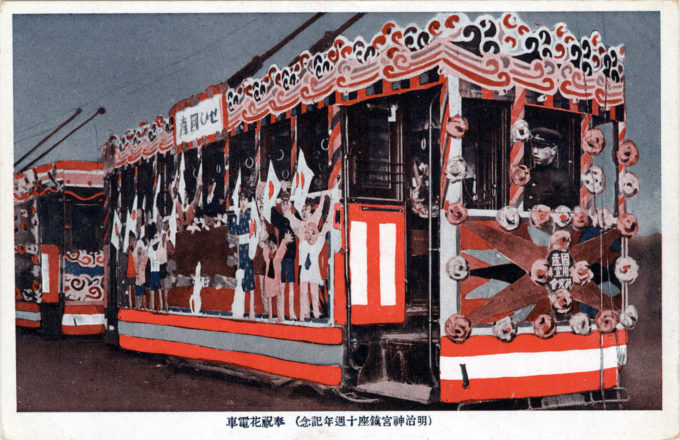

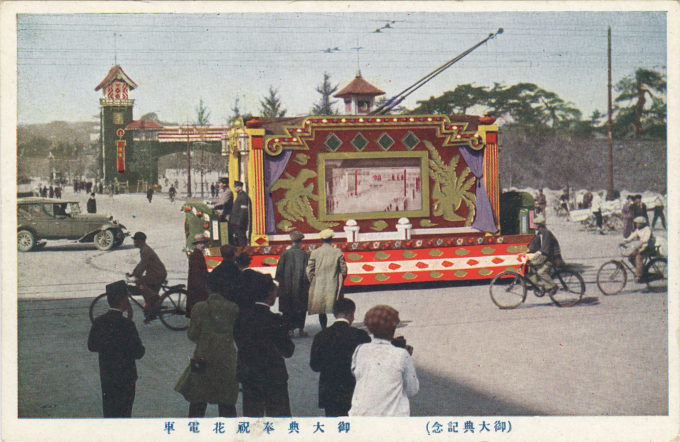

A streetcar decorated for the fifth anniversary celebration of Emperor Showa’s enthronement in 1928. The Taishō era’s end and the Shōwa (Enlightened Peace) era’s beginning was officially proclaimed on December 25, 1926, when Crown Prince Hirohito assumed the imperial throne upon his father, Yoshihito’s, death. Two years later, in November 1928, the new Emperor’s ascension was confirmed in ceremonies (sokui) conventionally identified as ‘enthronement’ and ‘coronation’ (Shōwa no tairei-shiki).

See also:

Rice culture, c. 1910

Crown Prince Hirohito’s tour of Europe, 1921

“There was no Coronation in Japan last week. There could be none. There is no Crown.

“The grand pageant of assumption of the Imperial Station proceeded amid ancient things and ceremonies whose very names and meanings are untranslatable. However, since the Tenno did sit upon what amounted to a chair, one may stretch a point and call the occasion his Enthronement.

“Preparations of the most laborious and costly sort began more than a year ago. Over $4,000,000 was spent on new equipment for railways, illumination, telegraphs, telephones, telephoto and radio. Since a little rice would be offered to the Sun Goddess by the Tenno, at one point in the ceremonials, a diligent search had to be made throughout the Empire for persons sufficiently exemplary to be entrusted with growing this rice.

“… Hirohito Tenno would now speak to the people the solemnest words of his reign. Augustly he arose and stood with the baton upraised. Then in very loud and ringing tones he cried: ‘Our Heavenly and imperial ancestors in accordance with the Heavenly truths, created an empire based on foundations immutable for all ages, and left behind them a throne destined for all eternity to be occupied by their lineal descendants. By the grace of the spirits of our ancestors this great heritage has devolved on us. We hereby perform the ceremony of enthronement with the sacred symbols …’

“… Although the ‘Enthronement’ was now complete — insofar as Occidentals understand that idea — there would be several more days of pomp, during which the Tenno would personally inform the Sun Goddess what had occurred and offer her with filial piety the sacred rice (boiled). Finally, with hearts uplifted and pure, Emperor and Empress will participate in three joyous Grand Banquets, visit the Shrines of the Imperial Ancestors, and lastly open the national Chrysanthemum Party, gayest fête of the Japanese year.”

– “Emperor Enthroned”, TIME Magazine, November 19, 1928

“The ceremonies were designed for large-scale public participation. During the celebration year, almost one million people visited the two paddy fields where the sacred rice was grown, while large crowds also attended other ceremonies. At Meiji Shrine in Tokyo, 12,532 invited guests sat at 700 tables for just one of the formal banquets at the Daijosai.

“… In concrete terms, the enthronement ceremonies served to display the nation to itself and also to extend the reach of national institutions and further implant the habit of thinking ‘nationally,’ through the power of technology and by other means … At times the connection between the modern and the supposedly ancient was quite explicit, as when the ‘celebration’ airplanes flew over the paddy fields in Shiga Prefecture as the sacred rice for the Daijosai was being planted.

“… No doubt the 1928 ceremonies further encouraged the merging in the public mind of ‘nation’ and ‘state’ – and of ‘state’ and ’emperor’ – making it harder to separate a consciousness of nation from the activities of the state and the symbol of the emperor. In that sense, the enthronement is connected with conservative nationalism. But people also loved festivals, were interested in clothes and food and celebrity, and were fascinated with the most modern things about their society.

“… Urban life was changing in the 1920s, and the ceremonies surrounding the emperor’s succession allow us a valuable glimpse of the impact of new developments on everyday life. Thanks principally to the media, people were participating more in public life and engaging with a version of the nation that was modern, unified, imperial, and technologically advanced.”

– Enthroning Hirohito: Culture and Nation in 1920s Japan, by Sandra Wilson, The Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2, September 2011

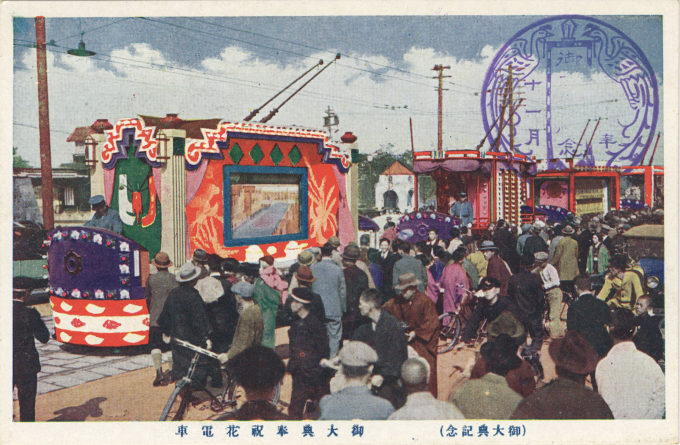

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.

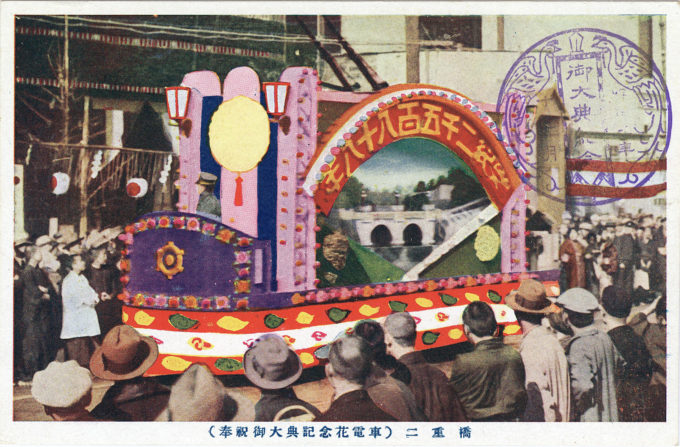

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.

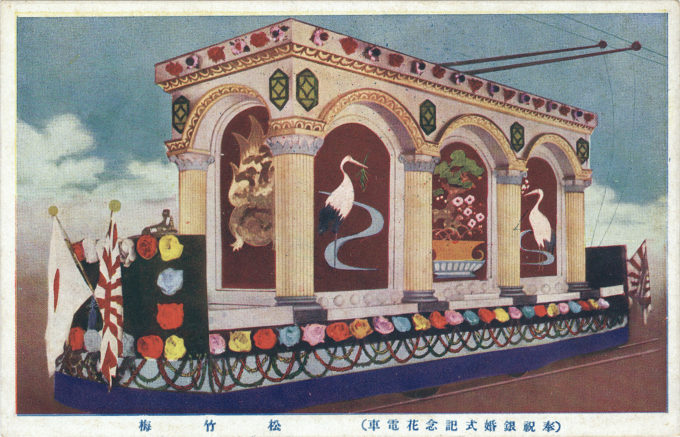

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.

- Street float celebrating the emperor’s enthronement, 1928.