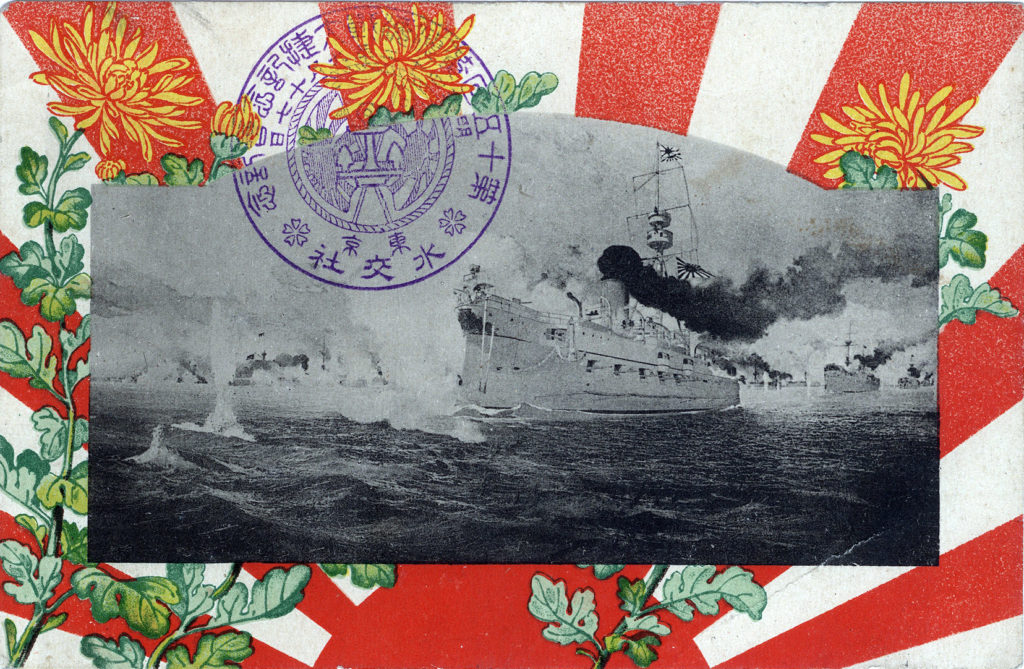

Battle of the Yalu River (1894) during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), published as a propaganda postcard for the sea battle’s 10th anniversary during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), c. 1905. The battle on Sept. 17, 1894 between twelve Chinese ironclads and eleven modern Japanese warships, including the cruiser Matsushima above, ended with a Japanese victory. Without the loss of a single ship the Japanese navy destroyed seven of the Chinese fleet and forced the others to seek refuge at Port Arthur. The sea battle afforded the world its first real view of modern steel men-of-war in action under fire, and offered naval and military experts their first opportunity to gauge the aptitude of the Japanese in their adopting of modern weapons and methods of warfare.

“Just one day after the rout of the Chinese from their defenses at Ping-Yang, another meeting between Japanese and Chinese took place not may miles from the same point, but the second battle was on sea instead of land, and its results were not as definitive as those of the battle of Ping-Yang.

“There remained room for each contestant to lay claim to certain phases of the victory. But the opinion of independent and impartial authorities, naval and military, has been that in the indirect results as well as the immediate lesson, Japan was well justified in claiming the contest to be hers.

“Admiral Ting and his fleet were at Tien-tsin awaiting the orders of the Chinese war council which was sitting at that place. He was instructed to convoy a fleet of six transports to the Yalu river and protect them while landing troops, guns and stores at Wi-ju, from which base China intended to renew operations in Corea. The transports were ready Friday, September 14.

“[Among the escorts were] five armored battle ships … The seven following were cruisers with outside armor, all of them built since 1881 and some as late as 1890. There were also in the fleet six torpedo boats and two gun boats. It is evident that the fleet was of modern construction, and without going into details as to the armament it may be said that the guns were equally modern in pattern.

“This splendid fleet arrived off the eastern entrance to the Yalu river on the afternoon of Sunday, September 16, and remained ten miles outside while the transports were to be unloaded.

“The work of disembarking troops and discharging stores proceeded rapidly until about ten o’clock Monday morning, September 17. Very soon after that hour, the sight of a cloud of smoke upon the horizon indicated the approach of a large fleet.

“The enemy was at hand, and the battle was impending. Admiral Ting immediately weighed anchor and placed his ships in battle array. His position was a difficult one. If he remained near the shore, his movements were cramped. If he steamed out for sea room he ran the risk of a Japanese cruiser or torpedo boat running in amongst his transports. He chose the least of two evils and decided to remain near the shore.

“By noon it was possible to distinguish twelve ships in the approaching Japanese squadron. The Chinese fleet steamed in the direction of the enemy and at a distance of five miles was able to distinguish the ships according to their types. Admiral Ting signalled his ships to clear for action and then brought them into a V-shaped formation, with the flagship at the apex of the angle.

“… The Japanese manoeuvred swiftly throughout the battle, and the Chinese scarcely had a chance for effective firing from beginning to end. When the Japanese were firing at the starboard section of the Chinese squadron, the ships of the port section were practically useless, and could not fire without risk of hitting their own ships.

“The Japanese cruisers attacked first one section and then the other. As soon as the Chinese on the port side had brought their guns to bear and had attained the range accurately, the Japanese would work around and attack the starboard side.

“At times as many as five Japanese vessels would bring the whole weight of their armament to bear upon one Chinese ship … As compared with that of the Japanese, the fire of the Chinese was very feeble and ineffective. The men fought bravely, however, and there appeared to be no thought of surrendering on either side, but a constant intention to fight to the end.

“… It is evident that there remained room for each side to claim the victory in this naval battle. The Chinese succeeded in disembarking the troops, which was the avowed object of their expedition. They fought brilliantly, inflicting considerable damage upon their opponents, and assert that the battle was terminated against their will by the withdrawal of the Japanese vessels.

“The Mikado’s men on the other hand, destroyed several of the best battle ships in the Chinese navy with great loss of life to the crews, and plead that the Chinese withdrew from them. The truth probably is that each fleet was so damaged and the men so exhausted with the long contest that they were mutually willing to quit.

“Inasmuch as casual spectators of impartial mind are not in a position to observe the details of a battle royal of this sort, it seems that the decision must be left unsettled except as the destruction of so many Chinese vessels may be certainly credited as a victory for the Japanese.”

– The War in the East: Japan, China and Corea, by Trumbull White, 1895

Pingback: “Imperial Head-Quarters during the [First] China-Japan War”, Hiroshima, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo