“Chicago is paying admiring homage to a young girl who has been the subject of almost as much news and editorial comment as the world war … [with] seemingly endless reams of paper of the Orient, explaining the impression that Katherine Stinson – a mere slip of a girl – made in China and Japan.

“About seven months ago this little lady ‘tied her airplane in a bundle’ and crossed the Pacific to the Orient. A constant series of exhibition flights in Japan and China followed. As she quaintly puts it, it was the first time the Orient ‘looked up’ to a woman. The way they looked up may portend much in international diplomatic circles. For, while some scholars of the Orient merely marveled at her grace and nerve (writing column after column in their queer hieroglyphics by way of expressing adulation), others saw more far-reaching consequences.

“The more learned of Japanese writers looked upon her visit as an indirect warning. It meant to them that if a mere girl could perform wonder feats in aviation the nation which produced that girl must have developed aviation to a point calculated to make it reckoned with in world circles.

“… She did more than visit and entertain Japan and China – she studied them. The Orient looked upon her as a sort of a goddess, and she responded with a sympathetic understanding of the people who idolized her.

“‘It is a great mistake to imagine the Chinese and Japanese belong to an inferior type of civilization,’ says this girl student gravely.”

– “Katherine Stinson Now in the Windy City”, The Billboard, June 16, 1917

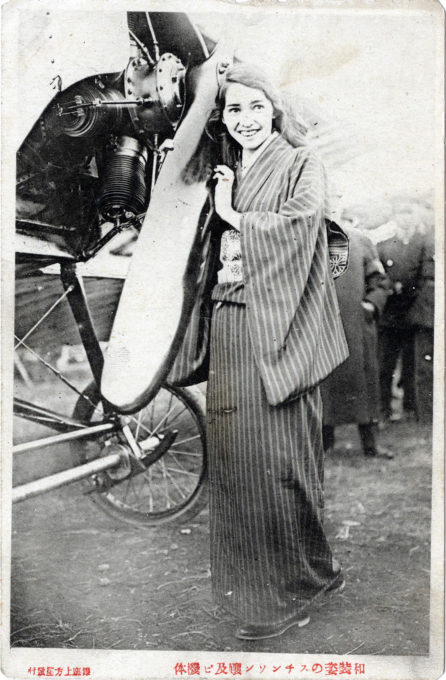

Aviatrix Katherine Stinson, “The Air Queen” and “Flying Schoolgirl”, in Japan, 1916. Stinson would make two visits to Japan … in December 1916 and again in September 1917. The “Flying Schoolgirl” was not all show. She was the first woman to fly solo at night, the first pilot (male or female) to perform skywriting, the first woman to fly for the U.S. Postal Service and, in December 1917, she set the American record for long-distance flying – 606 miles from San Diego to San Francisco. Stinson later broke her own record with a 783-mile flight from Chicago to New York.

See also:

Aviator “Bud” Mars, Japan, c. 1911.

Juichi Sakamoto, Pioneer Aviator, c. 1914

Aerial daredevil Art Smith, 1917

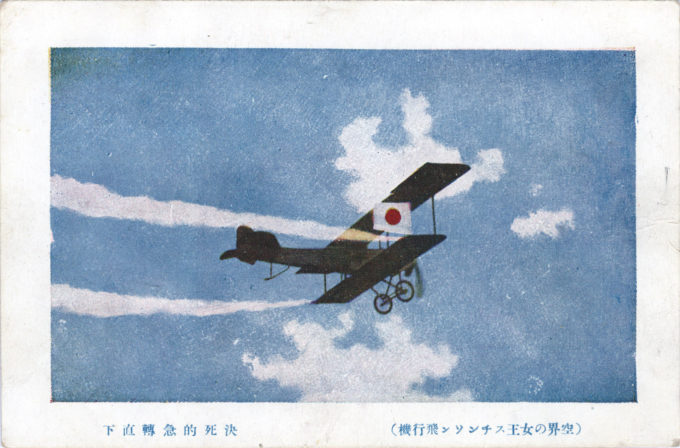

Katherine Stinson in Japan, piloting a Laird B-4 biplane loaned to her by its creator, Emil “Matty” Laird, c. 1916.

“During [Stinson’s] training period [in 1912], her first flight alone was a memorable near-disaster, as she recalled it years later. She had barely gotten up when the motor stopped. She remembered thinking: ‘Here is Mr. Lillie [her trainer] down below, and he has the $250 [she gave him for lessons] and I have the plane in the air and not knowing how to get down.’

“… Showing unusual deftness, she landed just inside the circle on the field, for a precise landing, a neat performance for a beginner and, more important, both pilot and machine were uninjured. Remembering the incident, Katherine felt she couldn’t fail, because people were very helpful; they were ‘all boosting for you.’

“After three weeks of instruction, Katherine applied to take the test for FAI (Fédération Aéronatique Internationale) certification. She passed her tests on July 19, 1912, earning license No. 148, issued on July 24 by the Aero Club of America – the American representative of FAI – to become the fourth U.S. woman pilot. The cover of Aero and Hydro featured her as ‘the only feminine Wright pilot in the world.'”

– Before Amelia: Women Pilots in the Early Days of Aviation, by Eileen F. Lebow, 2002

Katherine Stinson performs a nighttime barrel roll over the Kasumigaseki government district, Tokyo, 1916. Stinson is reported to have performed no fewer than six loops and was, according to some observers, garbed in Japanese kimono while barnstorming.

“Katherine Stinson was the fourth woman in the US to earn a pilot’s license, which she did on July 24, 1912 in a Wright Model B.

“On July 18, 1915, at Cicero Field in Chicago, Stinson became the first woman to perform a loop; she was also the first person of either gender to fly an airplane at night. She became known as the ‘Flying Schoolgirl’, flying exhibitions all over the country, even adding lights to her airplane and completing loops at night. She set many records, performed in Japan and China, and was the first woman sworn in by the Post Office as an air mail carrier.

“In 1916, the year Amelia Earhart graduated from high school, Stinson became the first woman to fly in the Orient. Fan clubs developed all over Japan to honor the ‘Air Queen’.

“When the United States became involved in World War I and the army asked for volunteer pilots, Stinson applied, but the military twice rejected her applications because she was a woman. Undaunted, she volunteered her services as an ambulance driver and was accepted. The combination of Europe’s cold climate and brutal wartime conditions proved, ironically, to be more injurious to her health than her career as a stunt pilot had been.

“When she returned from the war, she struggled to overcome tuberculosis by moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Her recuperation called for a new, less frenetic life, so Stinson traded in aviation for training in architecture. At the age of eighty-six, the ‘world’s greatest woman pilot’ died in Santa Fe on July 8, 1977. She is buried in Santa Fe National Cemetery.”

– Wikipedia