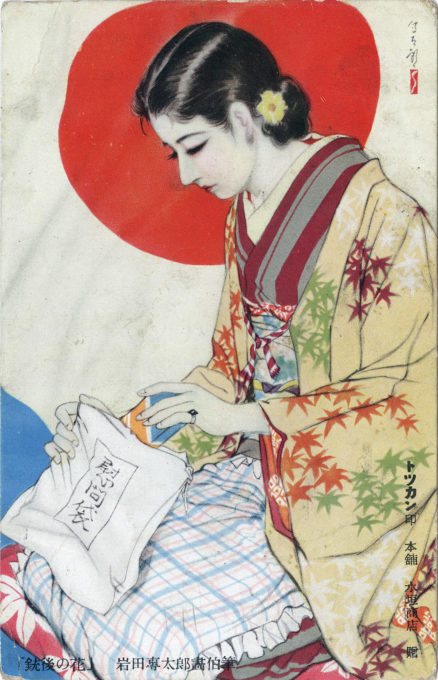

“Assembling a comfort bag” propaganda and advertising postcard, c. 1940. A “comfort bag” [imon-bukuro] was a gift package prepared by civilians to be sent to Imperial Japanese Army soldiers at the front containing articles not normally distributed in a soldier’s kit, e.g. toiletries, dried fruits, canned foods, and letters of encouragement. “Comfort bags” were as much of a morale booster for the civilians who assembled them as the bags were for the soldiers who received them. This postcard, while propagating the practice of imon-bukuro, also advertises Mizugako Shoten’s “Tokkan” [‘rush into the enemy’] branded bags for use as imon-bukuro.

See also:

Thousand-person Stitches (Sennin-bari) propaganda postcard, c. 1940.

Dai Nihon Kokubo-fujin (Greater Japan National Women’s Defense Association), c. 1940.

“Girls manufacturing parachutes”, propaganda postcard, c. 1945.

“A ‘comfort bag’ (imon-bukuro) was a bagged gift package prepared by civilians to be sent to Imperial Japanese soldiers for the purpose of encouraging them. The bag typically contained comfort articles not issued by the Japanese Military, e.g., toiletries, dried fruits, canned foods, sewing kit, protective amulets, and letters of encouragement. Bags were prepared by schoolgirls or local patriotic women’s societies.

“Among the items in the bags, the often-packaged comfort doll became significant to many Japanese soldiers. One account describes a soldier fighting in China holding onto a comfort doll, given to him by an anonymous young Japanese girl. The soldier, Obayashi, had no family to send him letters or extra supplies, so he relied heavily on the government distributed comfort bags. The doll became incredibly important to him as it represented a mother or a little sister that he is missing from his real life. When Obayashi was filled in combat, still in possession of his comfort doll, his fellow soldiers then preserved the doll and even redressed it with clothes created by the same young girl.

“Imon-bukuro made consumerism patriotic and in a time of rationing and privation, still profitable. An industry grew up around selling goods for imon-bukuro, such as Shiseido advertising it’s high-quality toiletries as ‘ideal’ for imon-bukuro making. Suntory produced miniature bottles of whisky designed to fit into the bags. Confectioner Morinaga made a special imon-bukuro tin for its delicious soft caramels.

“The imon-bukuro’s origin goes back to the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) and was popularized by Yajima Kajiko, a women’s education proponent and president of the Japan Women’s Christian Temperance Union. She believed that sending sweets and snacks from home would keep troops from drinking. Organized imon-bukuro gathering and distribution began with wives of the aristocracy funding and conducting charitable activities to support the military now being deployed abroad. This included sending imon-bukuro to the troops in Korea, Manchuria and even Japanese POWs in Russian prison camps.

“Early membership was made up of financially well-off elites who could afford such expenditures, but in time newer government-subsidized women’s organizations would come into being that the average woman could (or would be required to) join. The primary distributors of imon-bukuro from World War I onward until 1945 were various patriotic women’s associations.”

– Wikipedia