See also:

Electric Tram-Cars, Tokyo, 1904 (on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War)

Victory (Triumph) celebrations, 1905

Manseibashi Station (1912-1936)

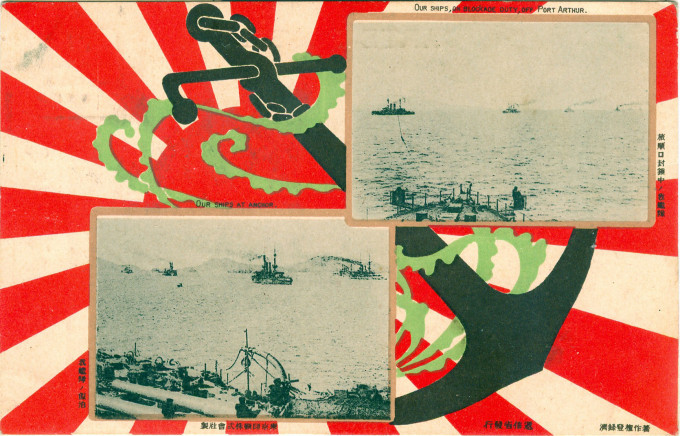

“Of all the phases of the war, it was the siege of Port Arthur which most gripped the imagination of the world. Indeed, towards the end its emotional significance clearly exceeded its strategic significance. For the Japanese, Port Arthur was the base which had been ‘stolen’ from them by the Russians, and symbolized what the war was all about. For the Russians, Port Arthur revived proud memories of the defense of Sevastopol during the Crimean War and was confidently expected to bring forth new acts of heroism to embellish their military tradition.”

– Russia Against Japan, 1904-1905: A New Look at the Russo-Japanese War, J. N. Westwood, 2002

From the wiki: “The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904–5 September 1905) was ‘the first great war of the 20th century.’ It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over Manchuria and Korea.

“Russia had demonstrated an expansionist policy in Manchuria dating back to the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century. Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of Korea as a Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused this, and demanded that Korea north of the 39th parallel be a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan. The Japanese government perceived a Russian threat to its strategic interests and chose to go to war by attacking the Russian eastern fleet at Port Arthur, a naval base in the Liaotung province leased to Russia by China.

“The resulting campaigns, in which the Japanese military attained complete victory over the Russian forces arrayed against them, were unexpected by world observers. The Russo-Japanese War would be concluded with the Treaty of Portsmouth, mediated by US President Theodore Roosevelt at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.”

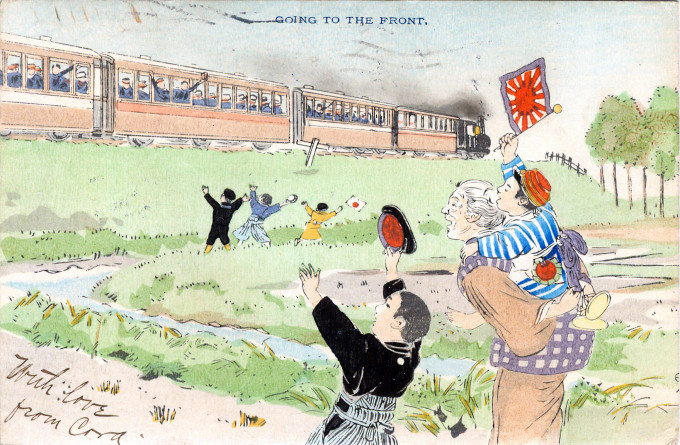

“The patriotism of the Japanese people strikes even an American as something extraordinary and phenomenal. I have seen women stick little cotton flags in the fists of the babies on their backs, and stand for hours beside a railroad track, waiting for a train-load of troops, satisfied if they could only throw a pack age of cheap cotton towels into an open window, or even wave their handkerchiefs once to the men who were going to the front.

“Soldiers who bid their friends or their families good-by bid them good-by forever, with the expectation and the assurance of death. Three or four days ago an English lady living on the ‘Bluff’ in Yokohama received a letter from a Japanese boy who had been employed in her house as a servant, and who had gone to Korea with the first reserves. After giving her some news of his health and his movements, he concluded by saying, in quaint and imperfect English:

‘Please remember, that though I will die, Nippon Teikoku [Great Japan] should have victory and honor.

(Signed)

Youth who unfear death,

Hiro Yamamoto’– First Impressions of Japan, by George Keenan, The Outlook, June 11, 1904

“At dead of night Japanese destroyers found the Russian Pacific Fleet at anchor in the outer harbour, peacefully asleep with its lights on. They fired their torpedoes and hit two Russian battleships, the Tsarevich and the Retvizan, and the cruiser Pallada. When day came, Japanese battleships shelled the Russian warships, which had retreated into the protection of their shore batteries. On the same day a Japanese army took control of Seoul, the capital of Korea, and on the 10th, Japan declared war.

“The Russians naturally complained at the breach of internationally accepted rules, but opinion in Britain generally favoured ‘Gallant Little Japan’ and in London The Times pronounced that ‘The Japanese Navy has opened the war by an act of daring which is destined to take a place of honour in naval annals.'”

– The Battle of Port Arthur began on February 8th, 1904, History Today, 2004

Pingback: Baron Komura, the plenipotentiary of peace negotiation, leaving Tokio, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Electric Tram-Cars, Tokyo, 1904 | Old Tokyo

Pingback: While her maid makes ready her bed, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Imperial Japanese Navy Cruiser “Soya”, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Anglo-Japanese Alliance, c. 1905 | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Benten-dori, Yokohama, c. 1906. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Victory (Triumph) celebrations, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Manseibashi Station (1912-1936). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Japan-US Relations, c. 1908. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Secretary of War Howard Taft & First Daughter Alice Roosevelt in Japan, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Emperor Meiji at the Grand Fleet Review, 1905. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: The Funeral of Commander Hirose, Tokyo, 1904. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Miyata Bicycle Co. New Year's card, 1933. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: “This is the Japanese greatest admiral …”, Admiral Togo, 1906. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “‘Eight-Eight’ Fleet Program”, Imperial Japanese Navy, c. 1925. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: St. John’s Episcopal Church, Asakusa, Tokyo, c. 1920. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “In commemoration of the Establishment of Direct Cable Communication between Japan and America” commemorative postcards, 1906. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: “The peace envoys of Japan and Russia at Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard”, 1905. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Ambassador’s residence, U.S. Embassy, Akasaka, Tokyo, c. 1950. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: Cruiser “Takasago”, c. 1900. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo

Pingback: “Battle of the Yalu River”, Russo-Japanese War commemorative postcard, 1906. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo