“Throughout the early Meiji years, factions of Confucianists, kokugakusha (national scholars) and Western scholars sought control of children’s education … The various accounts, policies, and proclamations of the early Meiji officials present a somewhat ambivalent view of children.

“On one hand, children were the embodiment of Japan’s hopes for the new era; on the other, a source of danger that could only be subdued through a rigorous regime of indoctrination, drills and endless recitations.

“A simplified narrative of this period would describe an initial phase of zealous Westernisation guided by liberal leaders, followed by a conservative reaction during the 1880s, culminating in the Imperial Rescript on Education of 1890 which sought to reconcile Confucian ethics with the new ideologies of nationalism and state Shintoism.”

– Raising Subjects: The Representation of Children and Childhood in Meiji Japan, by Rhiannon Paget, 2011

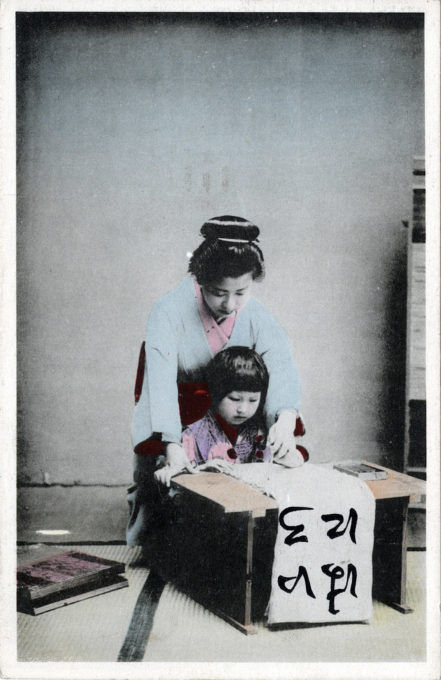

“Writing lesson”, c. 1910. A youngster practices writing hiragana, one of two Japanese-derived phonetic kana writing systems that supplement and complement the imported Chinese kanji system. Hiragana and katakana are used to write okurigana (kana suffixes following a kanji root, for example to inflect verbs and adjectives), various grammatical and function words including particles, as well as miscellaneous other native and non-native words for which there are no kanji or whose kanji form is obscure or too formal for writing.

In the postcard image above, the student has written “i-ro-ha-ni” [いろはに]. “Iroha” is a well-known Japanese poem, the first record of which dates from 1079 CE. It is famous because the poem is a perfect pangram, containing each character of the old 48-character man’yōgana syllabary exactly once. Because of this, it is also used to determine the ordering for the base characters of the present-day hiragana and katakana syllabary, in the same way the A-B-C-D sequence is used for the Latin alphabet. The first line of the poem, i-ro-ha-ni, can be interpreted as saying “The fragrant colors …”

See also:

Daini Middle School, Sendai, c. 1910.

The 1st Higher Middle School, Tokyo, c. 1910.

Early history of school lunches in Japan.

Iroha-zaka, Nikko.

“[T]he Japanese language in the early decades of the Meiji era can best be described as being in a state of chaos. Communication difficulties were compounded in the written form because the various spoken dialects bore little resemblance to kanbun (‘Chinese writing’).

“Literacy rates were very low perhaps because one had to master approximately 10,000 characters in order to be considered fully competent in kanbun. Instead, as Japan entered the Meiji era, it needed written and spoken forms of the language that were capable of acting as a unifying force for the new nation.

“Though several prominent language-reform advocates had begun to consider how written Japanese might best be reformed, the ruling elites could reach no consensus in the first two decades of the Meiji era.

“Men of renown such as Maejima Hisoka (1835-1919), Mori Arinori (1847-1889) and Fukuzawa Yukichi (1834-1901) had suggested ways kanbun might be simplified or somehow made more accessible to the average Japanese citizen. Mori, who would later become Minister of Education, had even considered a proposal to substitute English for Japanese! Nishi Amane (1829-1897), a prominent script-reform advocate of the era, recommended the complete abandonment of Chinese characters and that the Latin alphabet instead be adopted to write Japanese.

“By the late 1890s, the numerous options which had been bandied about by language-reformers in the early Meiji years had been narrowed to two: Either they would select a simplified version of the classical language (futsubun) or use a written form of the colloquial language spoken by the non-elite (genbun’itchi, which literally means ‘unity of the spoken and written language’), for example merchants, authors, managers, office workers, etc.

“The National Language Research Council was created by the Imperial Diet in 1903 to settle the matter. The members of this council were not revolutionaries. Members were prominent educators, journalists and government officials who wish to reform the language in a way that best suited the interests of the education system and the centralized state.

“In the end, the NLRC codified grammar, decided upon the fine points of writing characters, and agreed on a standard pronunciation (based on the Tokyo dialect). In addition, the Council considered the continuing problem of simplifying the large number of kanji and their complexity but came to no conclusion.

“Further kanji reforms had to wait until the end of the Pacific War amidst the reorganization and restructuring of the Japanese education system during the Occupation period. Students in Japan today are no longer required to learn the 4,000-5,000 characters pre-war students were tasked with memorizing.

“Now, the Japanese government has an approved list of 1,945 kanji for ‘general use’ called the jōyō kanji, of which slightly more than 1,000 are taught at the primary school level, becoming the de facto threshold of written literacy.”

– The Creation of the Modern Japanese Language in the Meiji-Era, by Paul H. Clark, 2022

Pingback: Iroha-zaka, Nikko. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo