“The innocent and inexpensive recreations that missionaries introduced to Karuizawa were by and large similar to those popular in Kodaikanal and other hill stations in India.

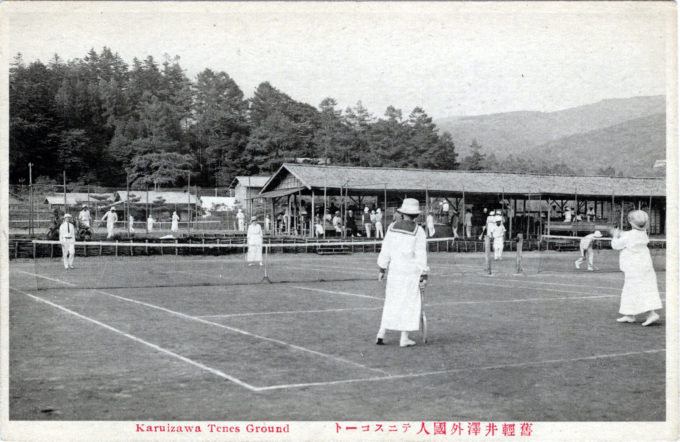

“In Karuizawa, tennis seems to have become almost the symbol of the village/town; the public tennis courts that the Summer Residents’ Association maintained was the place for social exchange as described by Kate L. Hansen:

‘Have I told you about the courts? These four together in a hollow; and just above them on the hill is a sort of covered grandstand which is the special center of Karuizawa for everybody goes there to talk, drink tea and incidentally once in a while, take a look at the games.'”

– Indian Ocean: The New Frontier, edited by Kousar J Azam, 2019

Play Ground in Karuizawa, Shinshu, c. 1930. Tennis remains a popular summertime recreation at Karuizawa, and has figured in at least one imperial wedding.

See also:

Karuizawa, c. 1920

View of Kose Station (Karuizawa), c. 1920.

Mikasa Hotel, Karuizawa, c. 1920

Imperial Wedding, 1959

International Village, Nojiri-ko (Lake Nojiri)

“[John] Nelson after completing an arduous trip up the old Usui Pass a few years before had told [Alex Shaw] Shaw about Kariuzawa’s unique climate in the summer.

“It was reminiscent of cooler areas in North America or Europe. The air was much dryer than the stifling humid summer air of Tokyo that bred epidemics of cholera, typhoid and small pox, not to mention a mosquito-borne disease called Nihon encephalitis.

“For missionaries with children, a desire to escape Tokyo for a few months in the summer could mean not only relief from hot muggy weather, but life or death.

“Now that the Meiji government had decided to put its first east-west railway connection along the Nakasendo route it was logical to come to Karuizawa.”

– Karuizawa Story: In Asama’s View, Stephen Fleenor, 2011

During the Edo period, Kariuzawa served as a post station town on the Nakasendō highway, called Karuisawa-shuku. In 1893, the trunk line from Naoestsu to Karuizawa was extended through to Tokyo. At Karuizawa, the coming of the railroad made it into an important transportation hub: all trains were coupled with or separated from the helper locomotives that were required of all trains for travel through the Usui Pass.

“What is the fascination of this little mountain ‘machi’? There are those who declare that Karuizawa in the only place in Japan where one can have the best of both worlds, the varying delights of Old and New Japan, the perfection of untouched natural scenery alongside the amenities of suburban life.

“It suits all tastes. Some go there for rest and quiet and the opportunity to study; others look forward to the golf, tennis, swimming, and even horse-racing, for there is an excellent race-course four miles away across the plain. The botanist, the bird-lover, and the entomologist all find themselves in the happiest of hunting-grounds. For the hiker, Karuizawa is beyond compare as the starting point for day-long walks through the woods and over the hills, and also for more ambitious trip to Ikao, Kusatsu, Nikko, or the Japan Alps.

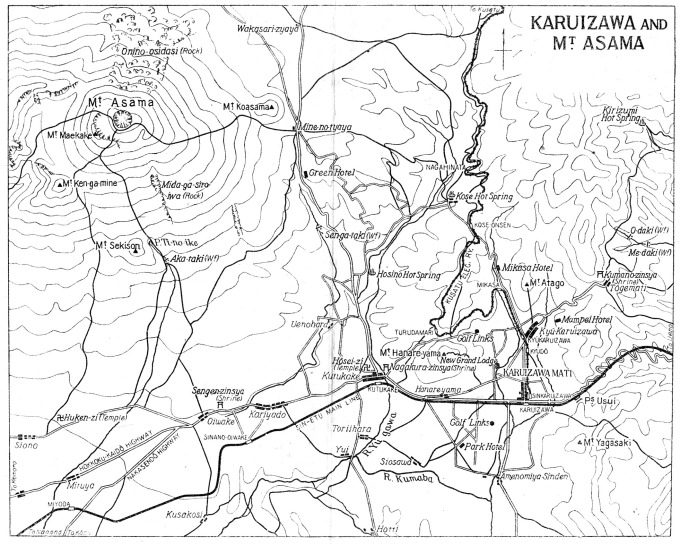

Map: Karuizawa and Mt. Asama. Kose Hot Springs is located north of Karuizawa and the Mikasa Hotel. (From “Japan: The Official Guide”, 1941.)

“… Nowhere in Japan does the air seem to fresh and cool after the sultry heat of the lowlands. An August morning in Karuizawa, with Asama clear-cut against a cloudless sky, ‘uguisu’ calling amongst the trees, the light mists trailing up Hanare-yama, and the promise of brilliant sunshine to continue, in an experience long remembered.

“… In addition to the natural charms of the neighbourhood there are the social and other interests. The organization of the resort is excellent. Not only do the hotels cater for the pleasures and comforts of all, but there is a Summer Residents Association which ensures the successful carrying out of the major activities. It arranges for concerts and cinemas, supervises the tennis, runs a summer school for children, cooperates with prefectural authorities in road repairs, issues maps and guidebooks, and exercises what H.G. Wells advocates as the ideal ‘control without government’.

“… Karuizawa’s popularity may be gauged by the fact that there are foreign residents in Japan who have expressed regret at having to return to their own country on furlough in the summer and thus miss the season at the mountain resort. It is cosmopolitan not only in its attraction for all the many nationalities in Japan, but in the appeal it makes to people abroad.”

– “Karuizawa and Nojiri”, Travel in Japan, Vol. 1 No. 2, 1935

Karuizawa’s history as a summer retreat goes back more than 100 years ago, to when British missionary Alexander Shaw visited the area in 1886. Karuizawa was by then a shabby village, a former Nakasendo Highway post station, fallen into disuse after the overthrow of the Tokugawa government and dwindling highway traffic, but Shaw fell in love with the cool climate and landscape, which is so often shrouded in mist; it reminded him of his English homeland. He found it an ideal summer retreat and built a summer house for his family — the first villa in Japan — and invited fellow missionaries and other foreigners to do the same. Wealthy Japanese and noble families followed suit, forming a unique community of intelligentsia influenced by Western culture.

In 1894, an old Japanese-style inn called Kameya was converted into a Western-style hotel and renamed Manpei Hotel. The opening of the hotel coincided with the first session of the so-called “Karuizawa Meeting”, a supra-denominational missionary meeting where hundreds of missionaries from all over Japan and China gathered every summer.

From the early 1920s through the 1930s, many distinguished Japanese artists, poets and novelists, such as Saisei Murou and Tatsuo Hori, also made Karuizawa their summer home. They left behind many works on Karuizawa that helped publicize the area and enhance its reputation.

After World War II, as Japan’s economy expanded and the middle-class grew, Karuizawa became a popular sports and leisure resort destination for the Japanese – offering tennis and golfing in the summer, skiing and skating in the winter. It was in Karuizawa, in the late 1950s, that the then-Crown Prince Akihito (the current emperor) met his future wife, Michiko, on the tennis courts. Since then, Karuizawa has also become something of a romantic destination for couples.

Pingback: View of Kose Station (Karuizawa), c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Mikasa Hotel, Karuizawa, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Karuizawa, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kumoba Pond, Karuizawa, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Imperial Wedding, 1959. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Swimming at the Seven Slope Pond, Karuizawa, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Karuizawa Union Church, Karuizawa, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: A history of tennis in Japan, c. 1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Mampei Hotel, Karuizawa, c. 1940. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo