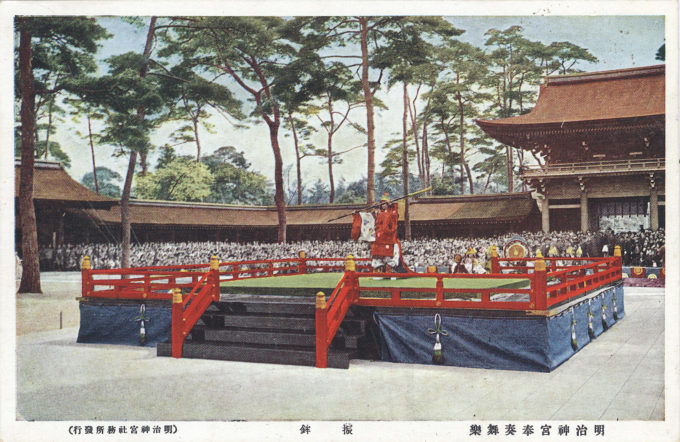

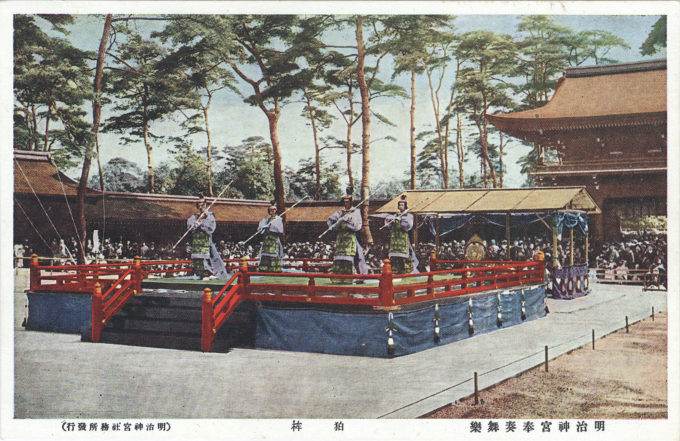

Meiji Shrine dedication, Manzairaku [“Long live the emperor” music] dance, 1920. After the Emperor Meiji’s death in 1912, the Japanese Diet passed a resolution to commemorate his vital role and leadership of Japan during its sustained drive to modernize and become equals with the West (aka the “Meiji Restoration”). An iris garden in the Yoyohata-machi area of of Tokyo (present day Yoyogi) where Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken had been known to visit was chosen as the building’s location. Construction was begun in 1915, formally dedicated in 1920, and completed in 1921 with the enshrinement of the Emperor and Empress.

(From the “Meiji Shrine priest dedication dance” postcard series.)

See also:

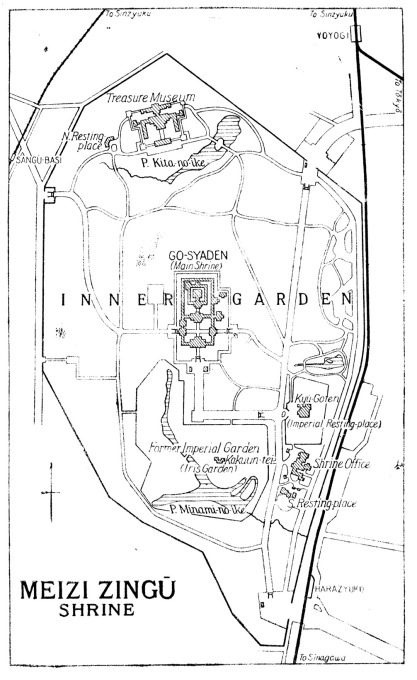

Meiji Jingu (Shrine), Tokyo.

Meiji Shrine Outer Garden & Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery under construction, c. 1925.

The building of the Meiji shrine is regarded by all as one of the best evidences of the undying quality of Japan’s faith in Shinto and the ancestor-worship for which it stands, especially the duty of worshipping the Emperor while on earth, and then after his ascension into heaven.

The triumph of the old faith of Japan is regarded as specially significant in the face of western ideas whose aggression is resented in the realm of religion. Japanese patriotism is still identified with the worship of the Imperial House, and as such must forever be different from that of other countries.

“Immediately after the emperor’s death on 30 July 1912, there was widespread support for the establishment of a place (shrine) and a date (3 November) to commemorate the late emperor.

“Notably, in many cases the establishment of these two memorials was proposed together … Furthermore, the acts of naming both the place and the date ‘Meiji’ played an important role in the process of forming the emperor’s commemorative time-space.

“… The date of 3rd November, Emperor Meiji’s birthday, was first designated as a national holiday in 1868. It was declared a day of commemoration and entitled tencho setsu [天長節, ‘Emperor’s birthday’ held from 1868-1948]. National holidays were first regulated and institutionalized during the Meiji period, serving to eliminate various folk festivals as holidays and stress the importance of imperial commemoration days.

“This designation of national holidays was an important part of the process of Meiji time formation. In the next few years almost all time measurement systems were drastically changed: the one-emperor one-era system was adopted (issei ichigensei, 1868), the calendar changed from the lunar to solar calendar, and the 24-hour [clock] system was introduced (both 1873). The resultant uniformity of the time system in the Meiji period has been associated with uniformity of power.

“… For many enterprising merchants … the inaugural Meiji shrine feast day [on 3 November 1920] was above all a good business opportunity. By late October 1920, more than 500 stalls had begun to prepare for the inaugural events. They were able to make huge profits, charging prices two or three times greater than usual … Among the cheapest souvenirs were post cards, which had become very popular collectors’ items from the end of Meiji into the beginning of the Showa period.

“Celebratory postcards for Meiji shrine completely outsold cards for the national art exhibition, which usually sold very well during November. Over 40 different sets of post cards featuring Meiji shrine were marketed by individual merchants as well as by the Home Ministry, and over 100,000 sets were sold in total.

“Particularly popular were the wide variety of cards made by individual sellers, as these were cheaper than those produced by the Home Ministry, and had more up-to-date pictures; the most sought-after cards were always those portraying the latest festive events.”

– Sacred Space in the Modern City: The Fractured Pasts of Meiji Shrine, by Yoshiko Imaizumi, 2013

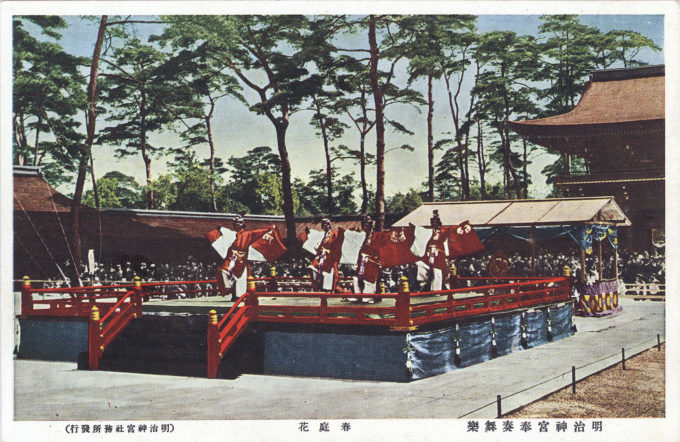

Meiji Shrine dedication, Kaniwa (incense garden flower) dance, 1920. Construction of Meiji Shrine began in 1915 under Itō Chūta, and the shrine was built in the traditional nagare-zukuri style, using primarily Japanese cypress and copper. The building of the shrine was a national project, mobilizing youth groups and other civic associations from throughout Japan, who contributed labor and funding. The main timbers came from Kiso in Nagano, and Alishan in Taiwan, then a Japanese territory, with materials from every Japanese prefecture, including Japan’s overseas possessions (Karafuto, Korea, Kwantung, and Taiwan) being utilized. (From the “Meiji Shrine priest dedication dance” postcard series.)