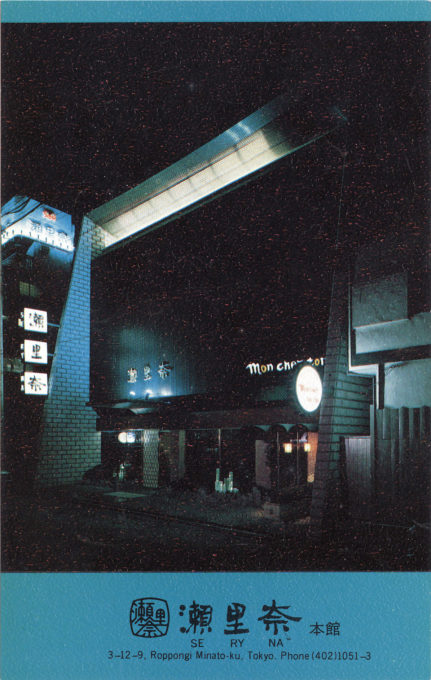

Seryna (left), serving shabu-shabu, and its sister establishment, the steakhouse Mon cher ton ton (right), Roppongi, Tokyo, c. 1970. The name “Roppongi”, which appears to have been coined around 1660, literally means “six trees”, the name derived from the fact that six daimyō [provincial lords] lived nearby during the Edo period, each with the kanji character for “tree” in their name. Legend also says that six very old and large Zelkova trees used to mark the area, with the last remaining tree destroyed during World War II firebombing.

See also:

Akasaka Mitsuke, c. 1910.

Asakusa Rokku (Theater Street), c. 1930.

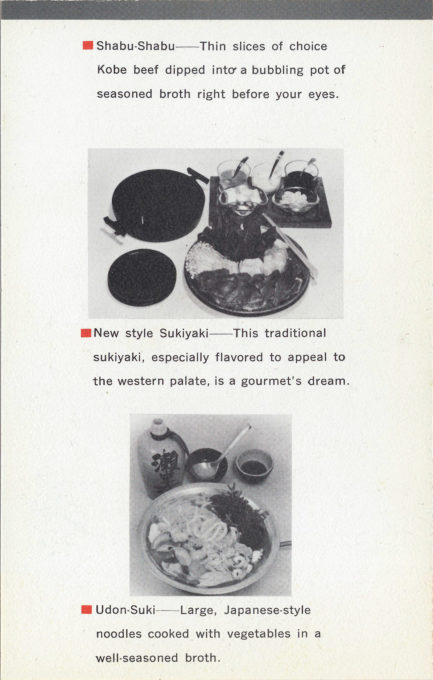

“Roppongi has many faces and many sides, and no one aspect, much less any one place of business, can represent it. Seryna Restaurant, for example, still a landmark in the neighborhood, opened in 1961 and is one of Tokyo’s largest and most famous choices for shabu-shabu and other Japanese meat dishes. It too has a history of foreigner and Japanese celebrity clients and its own ‘King of Roppongi’.

“… The iconic corner Almond coffee shop, said to be the first establishment in Japan to offer oshibori (moist hand towels) to customers as they got settled, opened at about the same time in 1964 in one of those newer structures and was reportedly overfilled from the first day.

“It too had a celebrity clientele, drawn in part from the TV Asahi studio nearby. It might be argued that the choice of Roppongi Crossing as the location for the neighborhood’s subway stop was itself a result of the presence of the television facilities.

– Roppongi Crossing: The Demise of a Tokyo Nightclub District and the Reshaping of a Global City, by Roman A. Cybriwsky, 2011

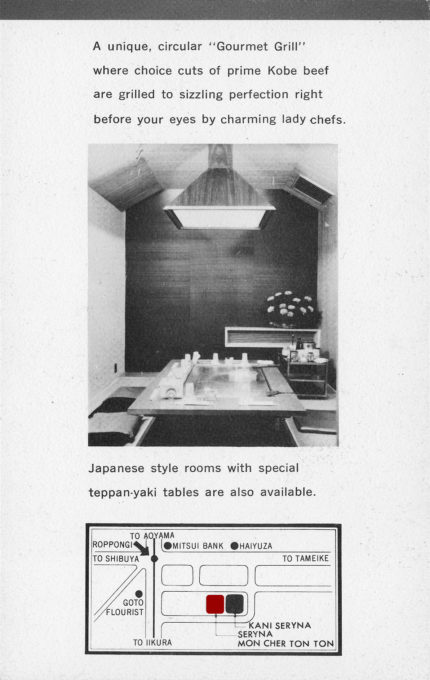

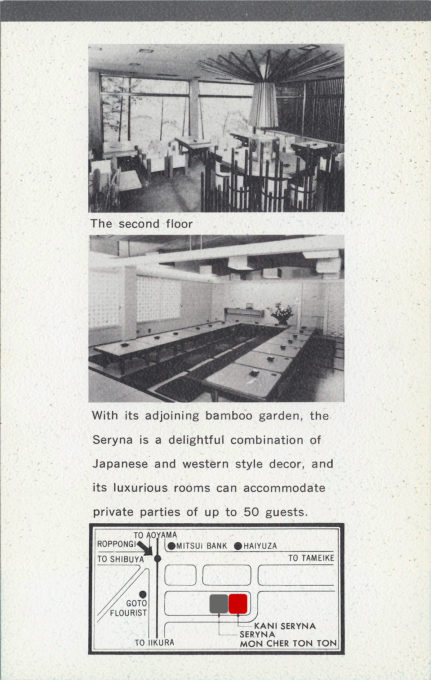

- Seryna, Roppongi, c. 1970.

- Seryna, Roppongi, c. 1970.

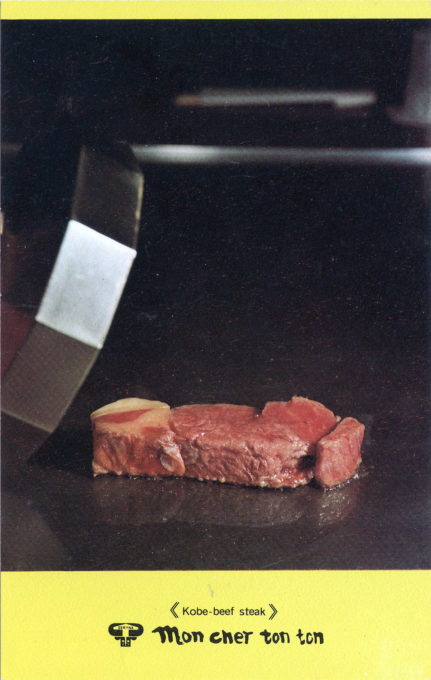

- Mon cher ton ton, Roppongi, c. 1970.

- Mon cher ton ton, Roppongi, c. 1970.

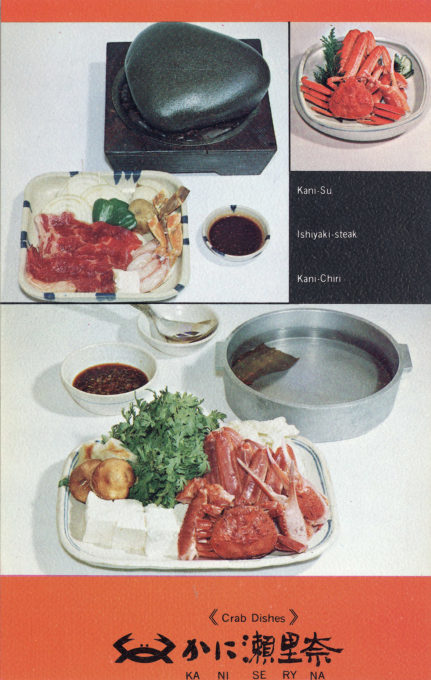

- Kani Seryna, Roppongi, c. 1970.

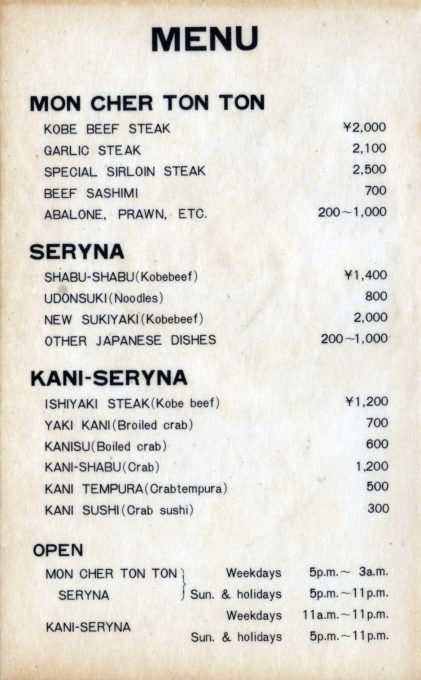

- Mon cher ton ton, et al. menu, Roppongi, c. 1970.

- Mon cher ton ton, Roppongi, c. 1970.

- Kani Seryna, Roppongi, c. 1970.

“During and after the Japan-China War of 1894, Roppongi grew famous as a heitai machi, or soldier town. Many troops shared rooms rented to them above local shops. The Russo-Japanese War in 1905 brought an even greater influx of military, and the little country town no doubt began to garner a reputation that stands today of catering to military men enjoying R&R.

“In 1911 and 1912 the jinrikisha were nosed to the roadsides by the coming of the first streetcars, stretching from Aoyama 1-chome, through Roppongi, to Mikawadai and, of course, linking with the rest of Tokyo.

“It was about this time that 13-year-old Kinzo Murata made his way from his family’s Ginza tailor shop, through the fields and woods, that still sprinkled the suburbs, to begin his life’s work stitching clothing.

“As he sewed in his shop a few yards from the main crossroads, he watched the continuing transformation of Roppongi.

“The first official foreign embassies opened in Roppongi during the early Taisho period, some 10 years before the Great Kanto Earthquake leveled nearly everything from Mt. Fuji to Tokyo. (Today, of Tokyo’s many embassies, 43 are rooted in Roppongi)

“… Murata figures the earthquake was the turning point, so to speak, of his quiet little neighborhood. The homeless stayed. Commerce prospered.

“The 600-year-old ginko tree got a few years older and life was tolerable. In 1925, the government railway’s Yamanote belt line fastened, putting Murata’s tailor shop and Roppongi permanently within the steel rail circumference of the city.

“World War II was not to be as lenient with Roppongi as the Great Kanto earthquake had been. Napalm bombs blanketed the city, converting it within a few months before the end of the war into a Dresden-like inferno. More men, women and children were killed in the fire bombing of Tokyo than in the American atomic bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“Roppongi was gone. Rubble. Standing in ruins that were once pine forest, then city, then nothing, a person could once again see clear to the sea. But there was little life between.

“Ironically, the same GIs who brought the bombs landed with the bread, and it was the Allied Occupation, with its high concentration of conquerors in Roppongi, that helped in post-war rehabilitation and internationalization of the area. The U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division and Signal Corps sprinkled the area and the Sanno military billeting facility (literally officer’s hotel) is still located only a figurative stone’s throw from Roppongi.

“… Along with, and perhaps because of, the number of international soldiers who roamed Roppongi, this Roppongi Zoku (Roppongi Crowd) as it was nicknamed, featured the latest fashions, hip slang and a tendency for keeping late hours. As the foreign troop presence dwindled, the late-night shops, bistros and boutiques found willing clientele among the Zoku and entertainers who favored Roppongi with their off-hours.

“Today, Roppongi rages like a gastronomic United Nations flaunting the culinary arts of at least 20 nations. Square foot per square foot, few districts anywhere can boast its awesome potential for killing such a myriad breadth of epicurean hunger.

“Murata has turned his tailor shop into a boutique, featuring the latest styles, denims, bell-bottoms and corduroys.

“… Kinzo Murata and his Roppongi have come a long way. The trees are gone, but Roppongi has turned into a gold mine. Murata, in addition to owning the boutique, is vice chairman and chief of the business department of the Roppongi Shopkeepers Association, as well as active politically as vice chairman of the Roppongi Town Council.

“But where does Murata – a man who has been intimately intertwined in the growth and greening of Roppongi, a man who knows its back alleys and secrets like few others – where does a man like Murata go when he steps out to dine?

“’I don’t,’ he says. ‘I never eat out. Always eat home. I can’t afford to eat out in Roppongi. It’s just too expensive.'”

– “Good ol’ six trees – the way it was”, by Gary Cooper, Tokyo Weekender, September 27, 2007