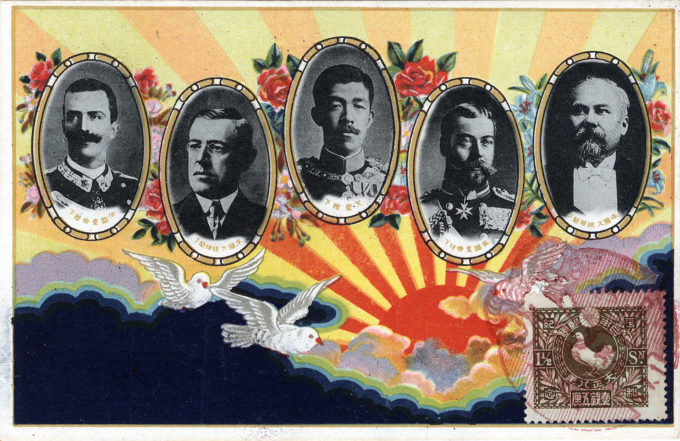

Victorious Great Powers at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. From left to right: Victor Emmanuel III (Italy), Woodrow Wilson (US), Emperor Taisho (Japan), King George V (Great Britain), Georges Clemenceau (France). Of the leaders pictured, only Wilson was in actual attendance at the Conference in Versailles, France.

See also:

South Pacific Mandates (Japan), c. 1930.

“Westerners dealing with Japan [in the spring of 1919] tended to fall back on stereotypes about the mysterious East. So much about Japan was curious, including its status in the world. Was it a major power or not? And was it entitled to have the same number of delegates as the other Great Powers? There were arguments both ways.

“Japan was very new on the world scene and until 1914 had confined its attentions to nearby East Asia. Even though it had declared war on Germany, it had not made a major effort on the Allied side. On the other hand, it did have one of the world’s three or four biggest navies (depending on whether the now-defeated German one was counted), an impressive army and a very favorable balance of trade. In the view of Borden, the Canadian prime minister, there were ‘only three major powers left in the world: the United States, Britain and Japan.’ When the League of Nations finally came into existence, Japan had the dubious honor of being ranked fifth in terms of contributions expected.

“… Japan’s delegation was dispatched to Paris with three clear goals: to get a clause on racial equality written into the covenant of the League of Nations, to control the north Pacific islands, and to keep the German concession in Shantung. Otherwise, according to instructions, it was to go along with Wilson’s Fourteen Points. The prime minister personally told Makino to cooperate with the British and the Americans. This was easier said than done.

“… The official British position at the Paris Peace Conference was to support Japan’s claims. Members of the British delegation made this quite clear when the Japanese asked anxiously for reassurance. Why did Britain only say that it would support Japanese claims, rather than guaranteeing that Japan would get the territories it wanted? Because that was all that Britain had promised to do in the secret agreement of 1917. Lloyd George himself said that Britain intended to stick by that promise.

“… [US President] Wilson was not prepared to confront Japan on the islands, because he was disputing its other demands, for instance for the German concessions in China. He confined himself to saying that the United States could not accept a Japanese mandate over Yap, which lies at the western end of the Carolines and was a major nexus for international cables. The Americans were to raise the issue of some form of international control from time to time over the next few years, but with no success. When the mandates were finally divided in May 1919, Japan got all the islands it wanted.”

– Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, by Margaret MacMillan, 2001

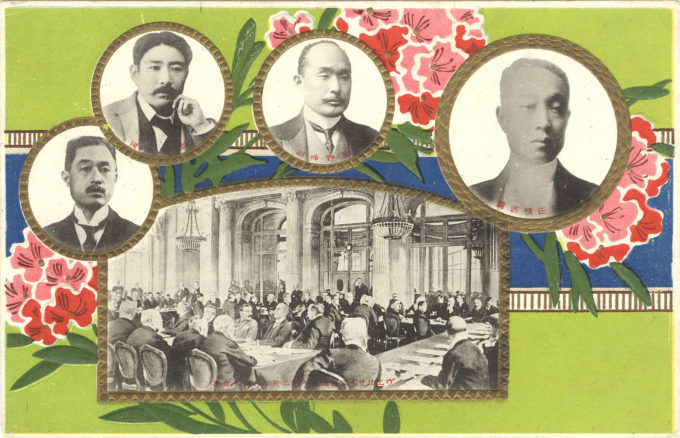

Japanese delegation to Versailles Peace Conference, 1919. From left to right: Ambassador to France and plenipotentiary Matsui Keishiro, Viscount (and former ambassador to the US) Chinda Sutemi, former Foreign Minister Baron Makino Nobuaki, and former Prime Minister Marquis Saionji Kinmochi.

“Versailles’ mixed legacy is even further complicated by a little-known attempt by Japan, one of the emerging players at the table, to move the world forward on the issue of racial equality.

“Japan asked for, and nearly got approved, a clause in the treaty that would have affirmed the equality of all nations, regardless of race.

“For all of the history forged, some historians believe the great powers missed a pivotal opportunity to fashion a much different 20th century.

“… Japan’s Racial Equality Proposal would have strengthened Wilson’s call for self-governance and equal opportunity. Yet, when the victors signed the treaty, that language was nowhere to be found … The rejection of the proposal would play a role in shaping the U.S.-Japan relationship, World War II and Japanese American immigration. It sheds light on the treatment of nonwhite immigrant groups by the U.S. and its legacy of white supremacy.

“… To be clear, historians say the Japanese were not seeking universal racial suffrage or improving the plight of black Americans, for example. But, the added language would have meant that Japanese immigrants coming to the U.S. could be treated the same as white European immigrants.

“France got behind the proposal. Italy championed it. Greece voted in favor.

“But Australia pushed back. The British dominion had instituted a White Australia Policy in 1901 limiting all nonwhite immigration. Australian Prime Minister William Morris Hughes strong-armed the rest of the British delegation into opposing the proposed clause and eventually got Wilson’s support too.

“… Wilson’s top priority at the conference was seeing the League of Nations created and the treaty ratified. The last thing he wanted was to alienate the British delegation, and he was not willing to let the Racial Equality Proposal derail those efforts. But, in a nod to appease Japan, he supported its demand to keep war-acquired territories like Shantung.”

– A Century Later: The Treaty Of Versailles And Its Rejection Of Racial Equality, by Josh Axelrod, NPR, August 11, 2019