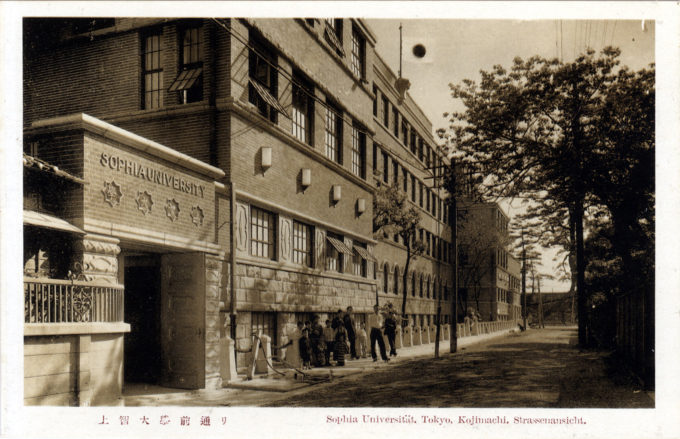

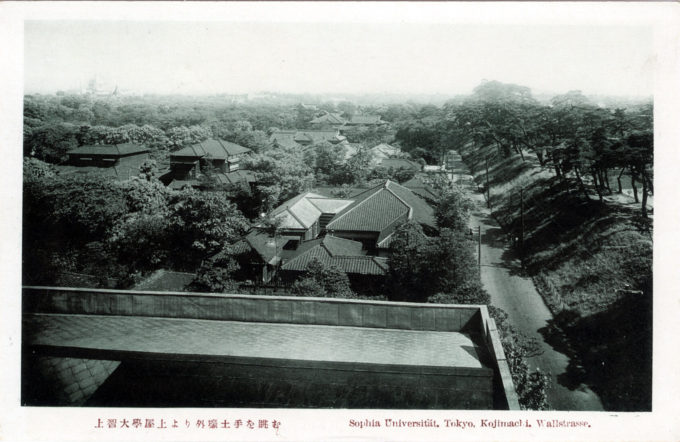

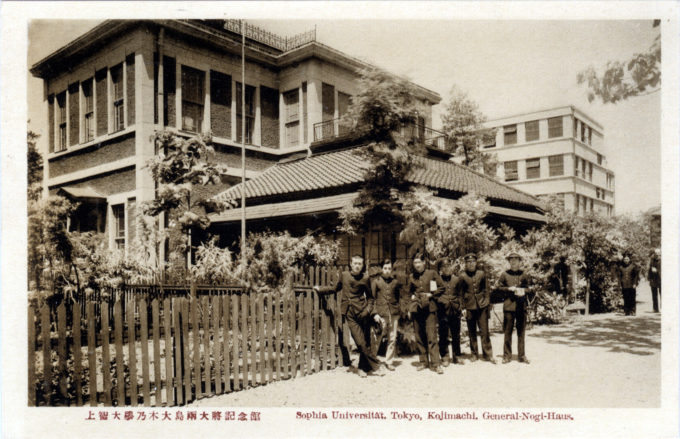

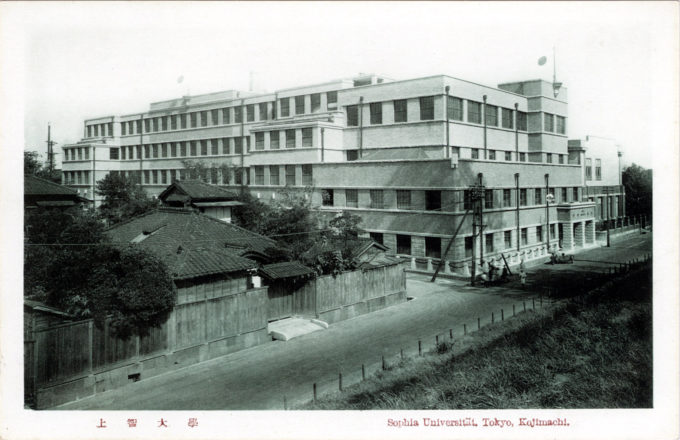

Sophia University, Kojimachi, Yotsuya, c. 1930. The university campus would be severely damaged in the waning months of World War II, during an April 13, 1945 firebombing of the capital by B-29 heavy bombers. According to the university records, 74 incendiary and two explosive bombs fell on the campus that night.

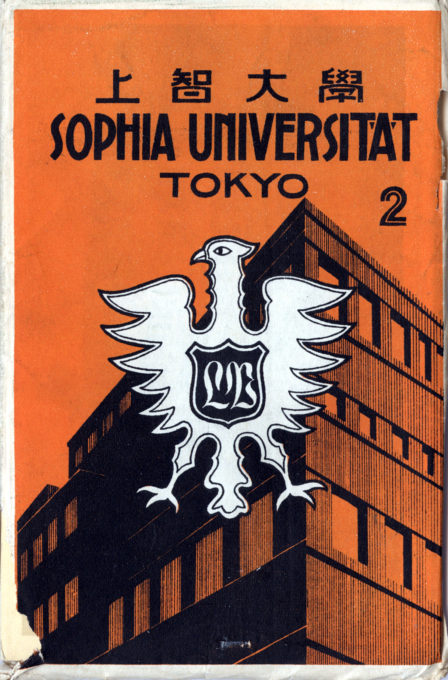

Sophia University (cover), c. 1930. The cover artwork displays the Germanic Jesuit origins of the school, featuring a stylization of the Prussian imperial eagle. Within the eagle are the initials “LV”, for the Latin Lux Veritatis (Light of Truth), the school’s motto.

“Sophia University (Jōchi Daigaku) is a private Jesuit research university in Japan, with its main campus located near Yotsuya station. Sophia University was founded by Jesuits in 1913. It opened with departments of German Literature, Philosophy and Commerce, headed by its German founder Hermann Hoffmann (1864–1937) as its first official president. Sophia University takes its name from the Greek Sophia meaning ‘wisdom’. Its Japanese name, Jōchi Daigaku, literally means ‘University of Higher Wisdom’. Sophia is ranked as one of the top private universities in Japan.

“Sophia University continued to grow by increasing the numbers of departments, faculty members and students, in addition to advancing its international focus by establishing an exchange program. Many of its students studied at Georgetown University in the United States as early as 1935. Sophia’s junior college was established in 1973, followed by the opening of Sophia Community College in 1976. With the founding of the Faculty of Liberal Arts in 2006, Sophia University presently holds 27 departments in its eight faculties.”

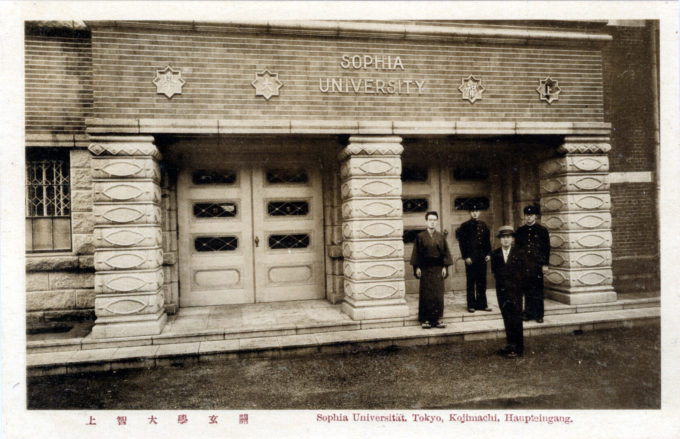

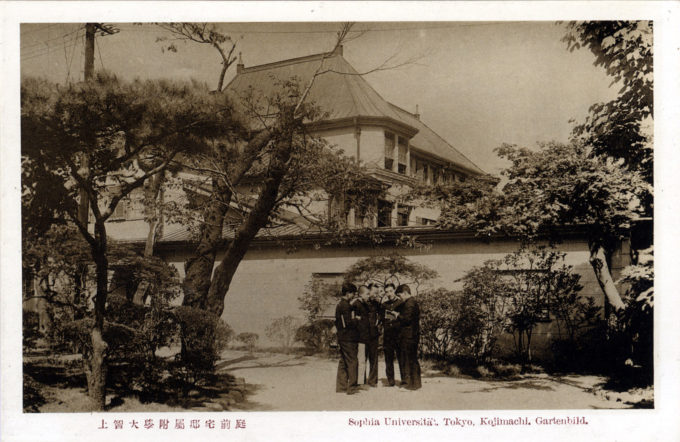

- Sophia University, Main Entrance, c. 1930.

- Sophia University, Main Entrance, c. 1930.

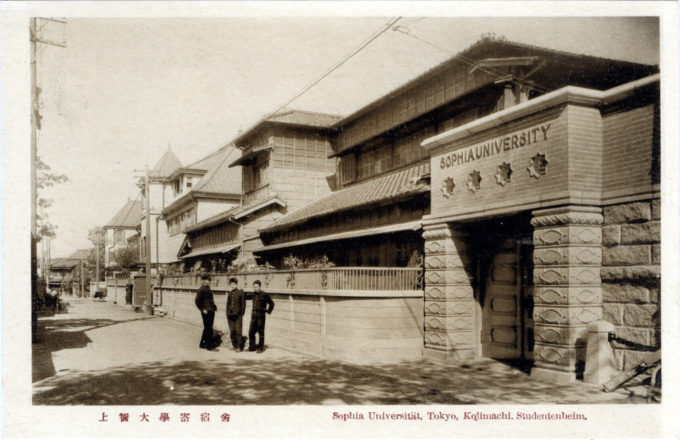

- Sophia University, student dormitories, c. 1930.

- Sophia University, Courtyard, c. 1930.

“In 1932, a small group of Sophia University students refused to salute the war dead at Yasukuni Shrine in the presence of a Japanese military attache, saying it violated their religious beliefs. The military attache was withdrawn from Sophia as a result of this incident, damaging the university’s reputation.

“The Archbishop of Tokyo intervened in the standoff by permitting Catholic students to salute the war dead, after which many Sophia students, as well as Hermann Hoffmann himself, participated in rites at Yasukuni. The Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples later issued the Pluries Instanterque in 1936, which encouraged Catholics to attend Shinto shrines as a patriotic gesture; the Vatican re-issued this document after the war in 1951.”

– Wikipedia

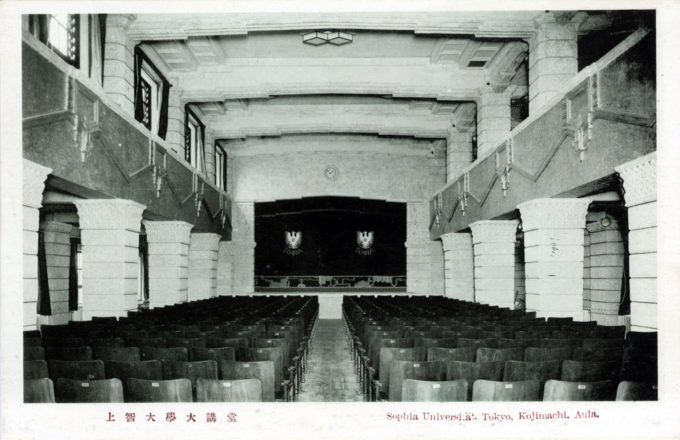

- Sophia University, Auditorium, c. 1930.

- “Wall street”, Sophia University, c. 1930.

- Sophia University garden, in summer, c. 1930.

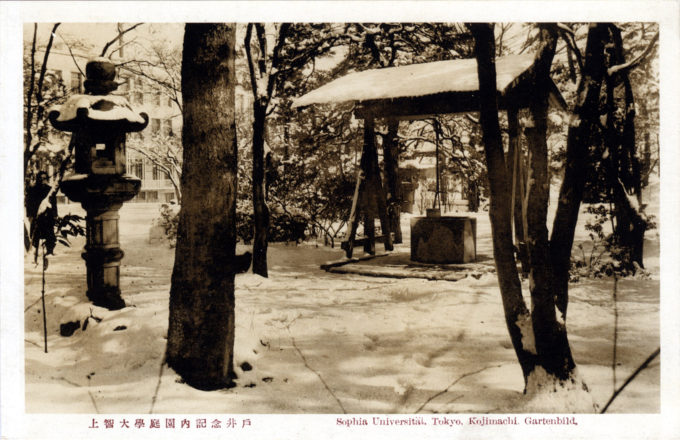

- Sophia University garden, in winter, c. 1930.

“[On the night of March 9-10, from] an overlook at the Jesuit Sophia University, Father Gustav Bruno Maria Bitter gazed out to see the first ‘circle of fire,’ which reminded him of ‘a silver curtain falling, like the lametta, the silver tinsel that we hung from Christmas trees in Germany…. And where these silver streamers would touch the earth, red fires would spring up.’ To Lars Tillitse, the incendiaries ‘did not fall; they descended rather slowly, like a cascade of silvery water. One single bomb covered quite a big area, and what they covered they devoured.’

“Bitter and Tillitse surveyed the attack from western and northern Tokyo, the hilly yamanote where the middle and upper classes made their communities. But the American targets were the packed wards of the lower, flat plain called the shitamachi, especially Honjo, Fukagawa, Joto, Edogawa, and Mukojima. ‘It was called the `plain side’ as distinguished from the `mountain side,” as it was once described, ‘the hills to the west and south dotted with residential districts.’

“The plain contained a vast overgrown tangle of wooden homes (‘massed like piles of dry wood at a building site’) and factories, finely veined with winding alleys, rather than streets, and stagnant canals. Apart from a few avenues and electric train lines, the only substantial feature was the Sumida River. On its left bank rested the Fukagawa docks facing Tokyo Bay, as well as the Honjo and Mukojima factory districts; along its right bank stretched Asakusa, Shitaya, and the outskirts of Kanda and Nihombashi. These communities, among the most densely populated in the world, had suffered heavily in the great 1923 earthquake. Lots in Tokyo typically measured twenty-five feet across at the street front but often were packed up to three houses deep. About 98 percent of the buildings were of wood and paper construction.”

– Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, by Richard B. Frank, 1999