See also:

Imperial Hotel (1890-1922)

Peacock Alley, Imperial Hotel

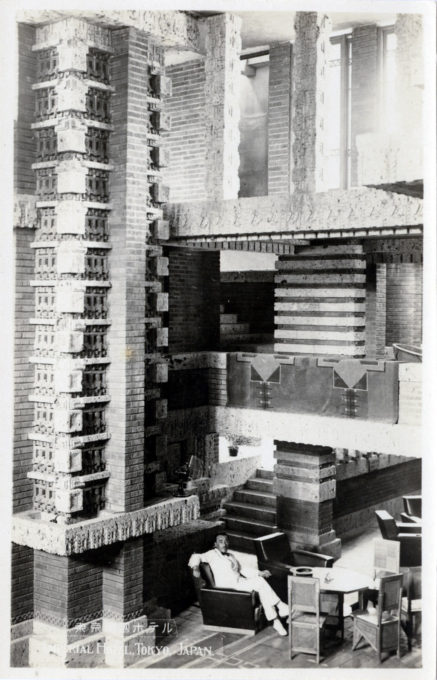

“The greatest success of the Imperial Hotel was the boldly monumental spaces Wright contrived to create in spite of restraints posed by the earthbound profile of the building with its purposely lowered center of gravity … It was valued for the opportunity it presented to distinguish building types by displaying a building’s character through a distinctive combination of ornament and plan.

“The design of the Imperial Hotel is proof of this state of affairs, in terms of which Wright hoped, as he always did, to rehabilitate and redefine architectural Truth.

“… In the Imperial Hotel, hierarchy of ornament was thus matched with hierarchy of spatial arrangement … The effect was charming and unusual, as many still alive will not hesitate to attest.”

– The Making of Modern Japanese Architecture (1868 to the Present), by David B. Stewart, 1987

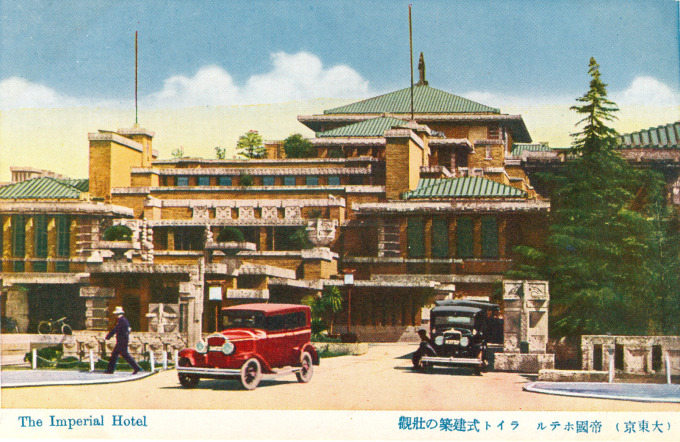

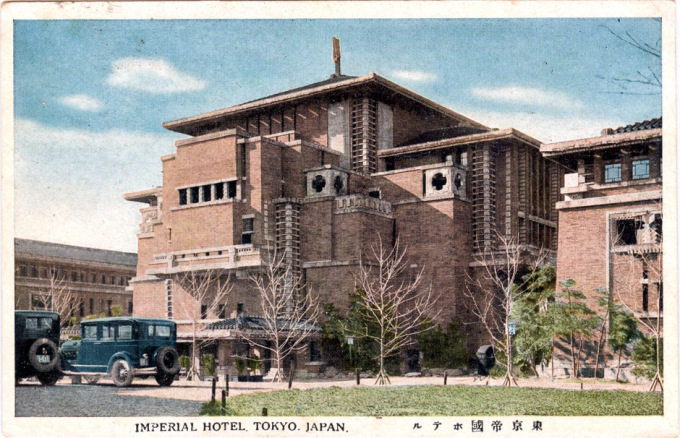

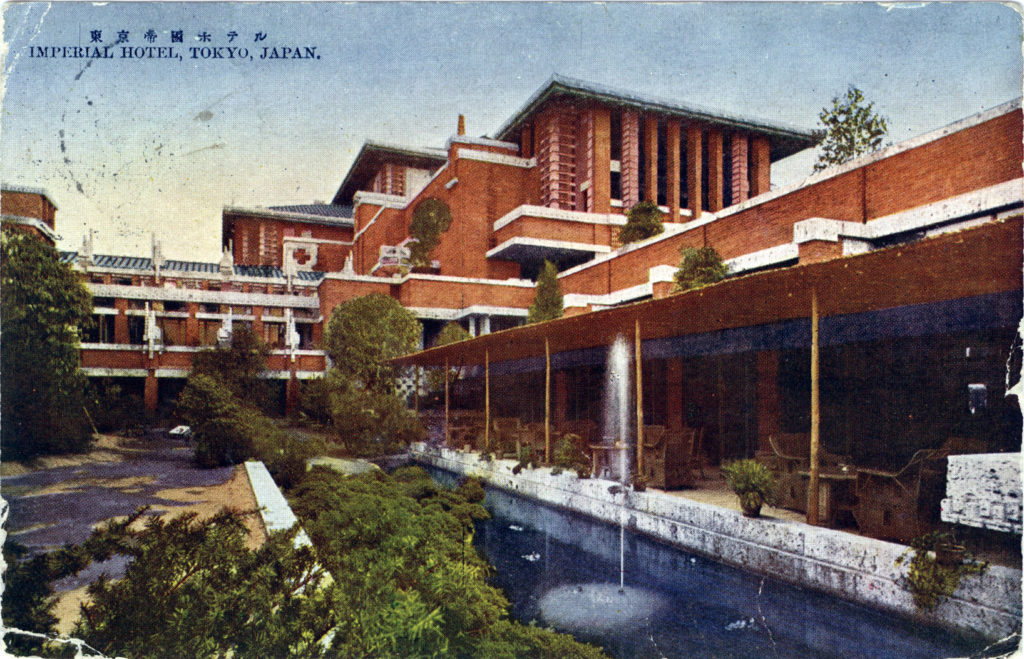

When a Tokyo old-timer recalls the Imperial Hotel [Teikoku Hoteru], they are, no doubt, remembering the luxury establishment that welcomed dignitaries and well-heeled visitors to Tokyo between 1923-1968, and which was known for two things: it famously survived the Great Kanto Earthquake only months after opening for business in June, 1923, and it was the most famous of six buildings in Japan designed and completed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright 1.

Under construction from 1915 to 1923, and made largely of volcanic stone and ferro-concrete, the Wright-designed Imperial Hotel enjoyed a 45-year reign as Tokyo’s premiere hotel. So highly-regarded was the Imperial that it was used after World War II (which it survived unscathed) as billeting during the Occupation of Japan for none but the most senior SCAP and Allied military personnel, and the leagues of Washington bureaucrats who paid the Japanese capital a visit.

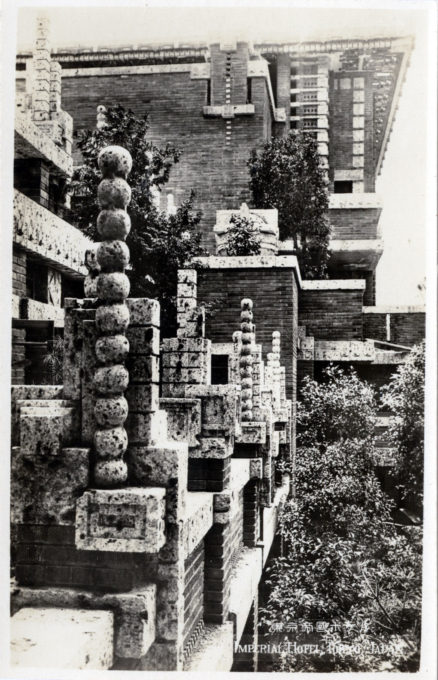

- Interior stonework, Imperial Hotel, c. 1930.

- Exterior stonework, Imperial Hotel, c. 1930.

“Undoubtedly the Imperial Hotel is one of the world’s finest structures in point of character, which is all its own. It is not difficult to recognize the genius which conceived such a poem in stone and brick, and due praise must be spontaneously offered to the brilliant engineering talent which adhered to strictly straight lines and flat arches throughout the entire building.

“The only fair comment that can be advanced is that the building is probably a hundred years ahead of the age in its architectural features and fifty years behind in many things which make for the comfort of its patrons. [Frank Lloyd Wright] sacrificed everything to his art, raising a monument to his genius and bequeathing to the Japanese the difficult task of making it a financial success.”

– “Architecture and the Buildings of New Tokyo”, The Far Eastern Review, June-July 1925

“The Imperial Hotel had been completed in 1923, and in early September the most powerful quake in modern Japanese history hit Tokyo, leveling large portions of the city. Wright had to wait ten days, during which newspapers claimed the Imperial Hotel was destroyed, before he received news in the form of a telegram from Baron Okura: ‘Hotel stands undamaged as a monument to your genius. Hundreds of homeless provided by perfectly maintained service.’

“Wright’s ‘jointed monolith’ had held firm, and the pools at the entrance – almost remove during final budget cuts – provided water to stop the fires that destroyed most of the neighboring buildings.”

– Frank Lloyd Wright, by Robert McCarter, 2006

Aerial view

Aerial view of the Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, c. 1930, across from Hibiya Park and the Kasumigaseki government district. To the right of the hotel is the Imperial Theatre.

Exterior views

- Imperial Hotel, front view, c. 1930.

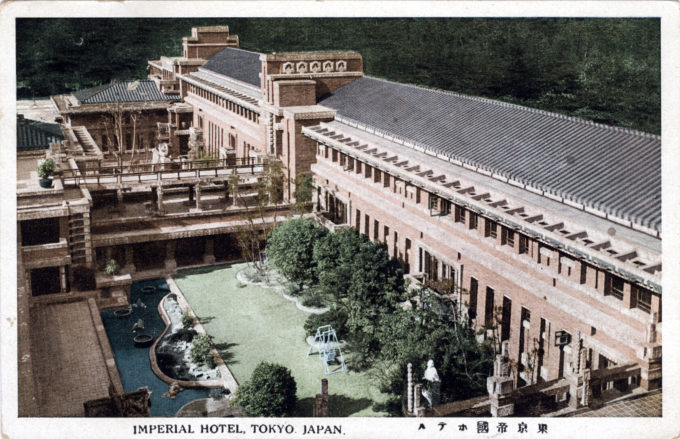

- Inner garden, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, c. 1940.

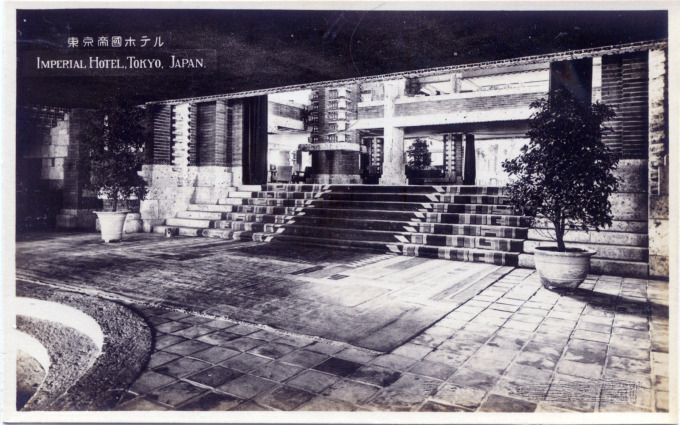

- Imperial Hotel, front entry, c. 1930.

- Imperial Hotel, rear entrance, c. 1930.

Interior views

- Imperial Hotel, lobby, c. 1930.

- Imperial Hotel, “Peacock Alley”, c. 1930.

- Imperial Hotel, Cafe Terrace, c. 1960.

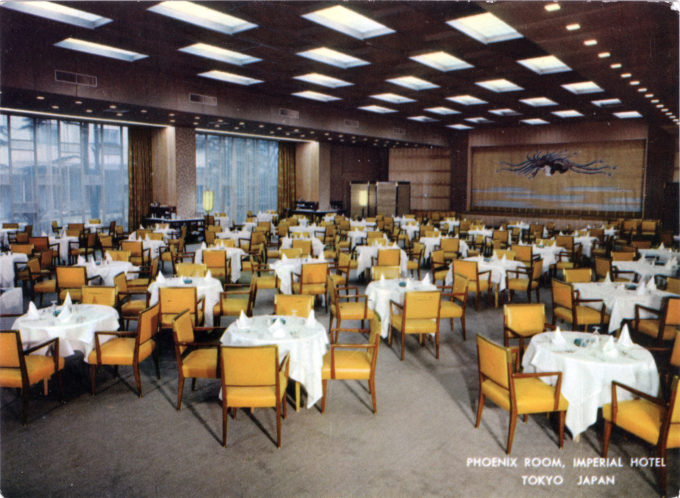

- Imperial Hotel, Phoenix Room, c. 1960.

By and large, though, the Wright-designed Imperial would eventually be considered by the post-war traveler to be dark and musty, and its un-airconditioned rooms too small. The hotel’s foundation, too, had by then settled unevenly into the soft subsoil; its long hallways and corridors came to have a wavy, rubbery appearance about them. A more modern but thoroughly plain (and very un-Wrightesque) multi-story annex was built behind the main building in the 1950’s.

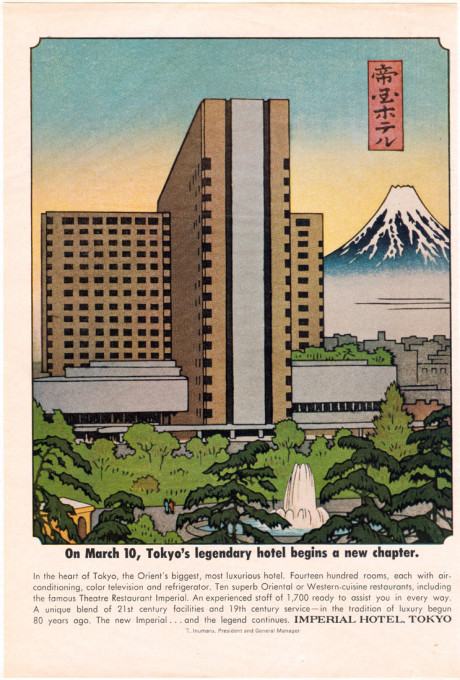

Magazine advertisement announcing the opening of the present-day Imperial Hotel, on March, 10, 1968.

Finally, in 1968, the Wright masterpiece was demolished and replaced by a gleaming, ultra-modern four-star edifice. All that remains of the “Wright” Imperial nowadays is the hotel’s front facade, preserved today at Meiji Mura, the outdoor architectural museum near Nagoya that hosts a large collection of Meiji era architectural art. Even though the Wright-designed Imperial was not a product of the Meiji era — as the first Imperial most certainly was — it came to symbolize for many people — Japanese and gaijin alike — the great degree to which Tokyo had matured during its first hundred years into a grand, majestic and, yes, a most civilized world city.

Pingback: Koshien Hotel, Nishinomiya, c. 1930. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Kamikochi Imperial Hotel, Matsumoto, c. 1940. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Peacock Alley, Imperial Hotel, c. 1950. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Wrightian Architecture Archives Japan | couses - top architecture schools

Pingback: Hotel Tokyo, Lobby, Marunouchi, c. 1950. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Veranda View of Kyoto, Miyako Hotel, c. 1910-1920. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Hibiya Park, c. 1910. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Nippon Beer, Ginza Beer Hall, c. 1950. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Icons and Oddities from the Massive Frank Lloyd Wright Archive ⋆ New York city blog

Pingback: Pipes d’opium #3 – The Swedish Parrot

Pingback: Imperial Hotel (1890-1922). | Old Tokyo

Pingback: Hotel Okura, Tokyo, c. 1970. | Old Tokyo

Pingback: A Virtual Tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lost Japanese Masterpiece, the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo - Elite Life Guide

Pingback: Frank Lloyd Wright und das Imperial Hotel in Tokio | Baukunst