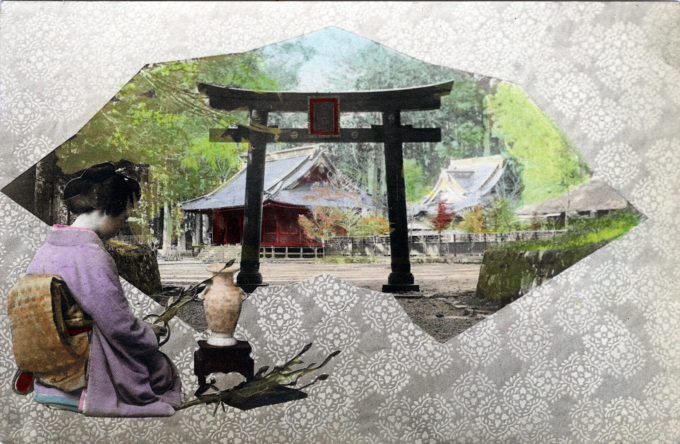

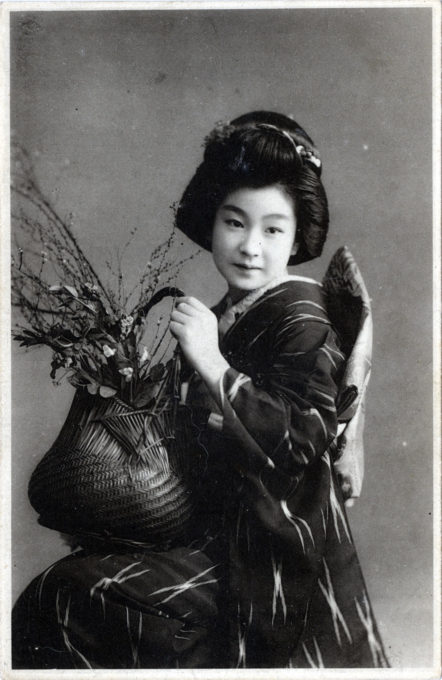

Maiko & New Years’ ikebana arrangement using pine boughs and flowers, c. 1910. The word ikebana is derived from the Japanese ikeru (“keep alive, living”) and hana (“flower”).

“The essence of ikebana is simplicity, and in contrast to Western flower arrangement, very few flowers, leaves, and stems are used to achieve the desired effect. Ikebana uses the flowers, the container, and the space around the flower arrangement as part of the artistic expression.

“… The essence of the Buddhist art is the Buddhist practice of the artist. The art itself is an expression of enlightenment and the creation of the art an act of enlightenment.”

– The Everything Buddhism Book: A complete introduction to the history, traditions, and beliefs of Buddhism, past and present, by Arnie Kozak, 2010

“In the Edo period (1603–1868), traditional arts were overwhelmingly male. Nishiyama estimates that only 1 percent of students in an average eighteenth-century tea school was female.

“Ikenobo, the largest and oldest of all ikebana schools, accepted only males of the elite classes, refusing to teach not only women but also commoners. Male dominance in ikebana scarcely changed in the early Meiji period (1868–1912), although traditional arts overall went into steep decline following modernizing reforms. Meiji-era changes in women’s compulsory education, however, led to a complete reversal of the gender ratio in ikebana in a few short decades. In 1899, the Ministry of Education mandated etiquette as a subject for higher girls’ schools, a category that subsumed sewing and knitting, home economics, and deportment, among other topics.

“… Always cognizant of the Western gaze, the Ministry of Education realized that pastimes like flower arranging and tea parties were viewed as feminine pursuits in the United States and Europe. In 1903, spurred by Imperial Prince Komatsu Akihito’s ‘order for revival/renaissance of kadō (the way of flowers),’ the Ministry added ikebana and chanoyu [tea ceremony] to higher girls’ school curriculums … By the 1920s and early 1930s, the tea ceremony and ikebana were universally accepted as significant aspects of the girls’ school curriculum.”

– “Flower Impowerment”, by Nancy Stalker, from Rethinking Japanese Feminisms, edited by Julia C. Bullock, Ayako Kano and James Welker, 2018

“This art called Ike-bana consists in expressing some poetic thought by an arrangement of flowers, grasses, leaves, bamboo and pine branches along certain well defined lines of composition. They must be in the form of a triangle for the old monks who were so instrumental in developing this art saw the Diety in everythin.

“The main stalk, or shin as it is called, bends out and up, the tip returning to a position vertical with its base. The other two, called soy and tai, are attendants or supporters. Smaller stems are used to fill in the hollow of spaces. A good ‘arrangement’ has no hollows or crossed stems. Every leaf-tip and flower must lookup to the main stalk for it represents the power of heaven. Man and earth, the second and third stems, look up to this power. Instead of the trinity of heaven, man and earth, some Flower Masters see the principle of father, mother, and child.”

– “Japan’s Gentle Art: Flower Arrangement”, by Eloise Roorbach, Japan Overseas Travel Magazine, February 1931

“Ikebana (‘living flowers’) is the Japanese art of flower arrangement, also known as kadō (the ‘way of flowers’). More than simply putting flowers in a container, ikebana is a disciplined art form in which nature and humanity are brought together; to arrange flowers to represent heaven, earth and humanity.

“Although the precise origin of ikebana is unknown, it is thought to have come to Japan as part of Buddhist practice when Buddhism reached Japan in the 6th century. The offering of flowers on the altar in honor of Buddha was part of worship. Ikebana evolved from the Buddhist practice of offering flowers to the spirits of the dead.

“The first classical style of ikebana, the school of Ikenobo, started in the middle of the fifteenth century; the first students and teachers of ikebana were Buddhist priests and members. Ikenobo began with a priest of the Rokkaku-dō Temple in Kyoto who was so skilled in flower arrangement that other priests sought him out for instruction. As he lived by the side of a lake, for which the Japanese word is ‘ike’, and the word ‘bo’ meaning priest, they are contracted by the possessive particle ‘no’ to give the meaning ‘priest of the lake’: ‘Ikenobo’. Thus, the name ‘Ikenobo’ became attached to the priests there who specialized in these altar arrangements. As time passed, other schools emerged, styles changed, and ikebana became a custom among the Japanese society.

“Contrary to the idea of floral arrangement as a collection of particolored or multicolored arrangement of blooms, ikebana often emphasizes other areas of the plant, such as its stems and leaves, and draws emphasis toward shape, line, form. Though ikebana is a creative expression, it has certain rules governing its form. The artist’s intention behind each arrangement is shown through a piece’s color combinations, natural shapes, graceful lines, and the usually implied meaning of the arrangement.”

– Wikipedia

Pingback: Ikebana (flower arrangement), c. 1910. | aStory